Thom Gobbitt (Austrian Academy of Sciences)

My focus here is on violence and the rules systems of Tabletop Roleplay Games (TTRPGs), to address the question of whether rules for violence would be integrated with or separated from the rules for other, more social skills – such as the pursuit of a law case – as a theoretical concern in my ongoing project to gamify the early medieval Lombard laws. Violence in TTRPGs has received increasing scholarly attention over the last decade or so, such as the implications of “combat time” (Torner 2015; Bowman 2010).

In a case study of “Player’s Handbook” from Dungeons & Dragons (D&D, Crawford 2014), Sarah Albom explores in “The Killing Roll” (2021) how the rulebook pushes players towards violent, combative responses – regardless of the actual situations they find themselves in. Problems are untangled (and made) through the appliance of violence. More generally, it is a truism of TTRPGs that the underlying rule system usually adapts the same mechanics used to resolve combat to the performance of any form of action, whether physical, social or intellectual. In using a rule system intended to resolve the outcome of a violent exchange, other activities effectively also become, metaphorically, at least, forms of violence themselves. Many “indie” TTRPGs – medieval themed or otherwise – have sought to break this connection, with numerous systems even going so far as to exclude combat entirely.

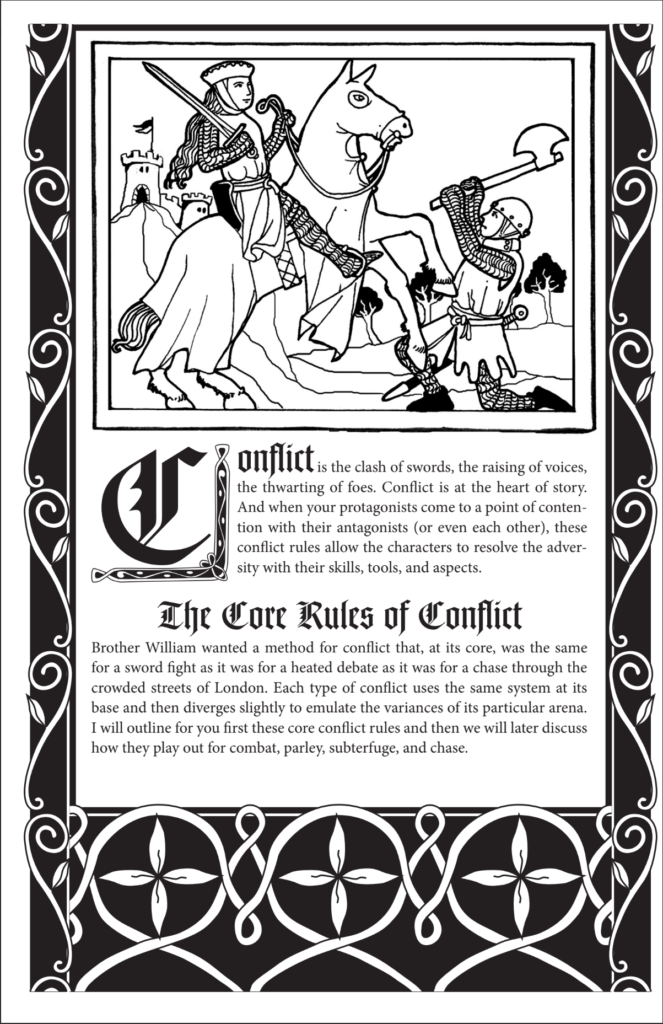

Conversely, others have embraced it. Jeremy Keller’s Chronica Feudalis (2010), offers a rule system that brings storytelling to the forefront (White 2014, 24), and centres the drama of interpersonal “conflict”, through an eponymous chapter arranged into four main categories : “Chase”, “Combat”, “Parlay”, and “Subterfuge”. Of these, “Combat” is addressed first in the rules, and described as “the epitome of human conflict”, underscoring how the other interactions can (and should) be read in comparable terms (Keller 2010, 67). “Parlay” covers a wide range of social interactions, and is where legal disputes would be resolved in the rules, although law itself is not actually named or explored here.

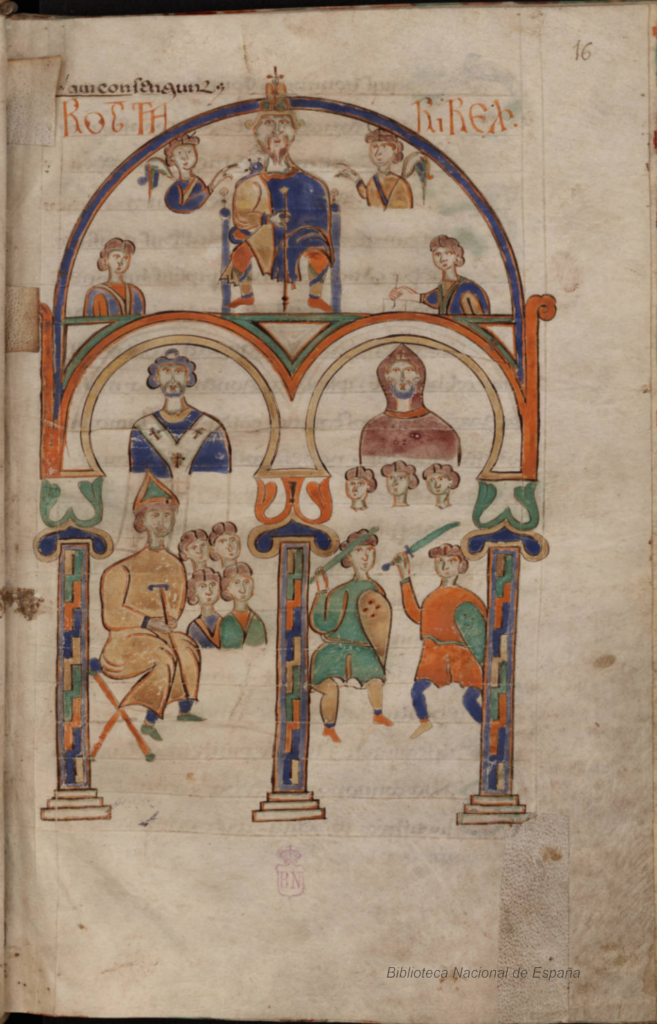

Turning to Lombard Italy and the Edictus Rothari of 643 CE (Ubl, Trump, and Schulz 2012), does it make sense to base the rule system as a whole on the specifics required for combat? The laws clearly offer grounds to make all social encounters metaphorically combative, with the resolution of social disputes being a recurrent theme. Moreover, the laws often recognise that verbal disputes could easily break into combat. Here, then, Albom’s earlier observations on the rules of D&D encouraging violence (2021, 13), seem to reflect a desirable means of implementing the very concerns that the Lombard law-givers were setting themselves against.

Furthermore, Edictus Rothari, §125 describes a blow against an enslaved fieldworker with the term pulslahi (setting compensation at half a solidi per blow if it leaves a bruise or cut: Francovich Onesti 2000, 112; Bluhme 1868, 29). A little later in the law code (Edictus Rothari, §228), we see the verb pulsare [to beat] describing the bringing of a law-case against another person (in this case claiming another person is illegally holding some property, and therefore much further from the inflicting of violence mentioned before: Bluhme 1868, 56–57). Despite the widely different subject matter, both of these laws (and others), use words with the same stem, puls- , indicating that for the Lombards striking an opponent with fist or law-case was essentially comparable. As law and combat comprise different faces of violence, should then the rules system for an early-medieval set TTRPG embrace this similarity, rather than fret about separating them into a false dichotomy?

Bibliography

Albom, Sarah. 2021. ‘The Killing Roll: The Prevalence of Violence in Dungeons & Dragons’. International Journal of Role-Playing 11:6–24.

Bluhme, Friedrich, ed. 1868. ‘Edictus Langobardorum’. In Monumenta Germaniae Historica, 4:1–205. Leges. Hannover: Hahn.

Bowman, Sarah Lynne. 2010. The Functions of Role-Playing Games: How Participants Create Community, Solve Problems and Explore Identity. Jefferson, NC; London: McFarland.

Crawford, Jeremy, ed. 2014. Player’s Handbook. 5th ed. Dungeons & Dragons. Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast.

Francovich Onesti, Nicoletta. 2000. Vestigia longobarde in Italia (568-774): Lessico e antroponimia. 2nd ed. Rome: Artemide.

Keller, Jeremy. 2010. Chronica Feudalis: A Game of Imagined Adventure in Medieval Europe. Blue Knight. Minneapolis, USA: Cellar Games.

Torner, Evan. 2015. ‘Bodies and Time in Tabletop Role-Playing Game Combat Systems’. In Wyrd Con Companion 2015, edited by Sarah Lynne Bowman, 160–71. Orange, California: Wyrd Con.

Ubl, Karl, Dominik Trump, and Daniela Schulz, eds. 2012. ‘Leges Langobardorum’. In Biblioteca Legum: A Database on Carolingian Secular Law Texts. Cologne: Universität Köln. http://www.leges.uni-koeln.de/lex/leges-langobardorum/.White, William J. 2014. ‘The Right to Dream of the Middle Ages’. In Digital Gaming Re-Imagines the Middle Ages, edited by Daniel T. Kline, 15–28. London and New York: Routledge.

Thanks Thom for sharing your work! I’ve been following your progress throughout the different MAMG events and really looking forward to seeing where it leads you. Could you share a bit how far along you are in terms of finishing a prototype for the game? And if people would like to engage with it, how can they do it?

Hello Mariana,

Thank you for the reply – and for the watchful eye over my progress 🙂 I’m looking forward to seeing where it goes too

Progress on the game is unfortunately still rather slow, and on the one hand always seems to get pushed back by every other thing and comittment that comes along, and on the other gets derailled as i think of new things to add in – things which inevitably require a re-write of parts i was certain worked…

So at the moment there’s no real schedule. But I’ll be running at least one play test, hopefully more, at the IMC in Leeds next month, and I post occasionally about it on Bluesky under the hashtag #LangobardRPG. and will always try to answer any questions. But, yes, i really need to a) press on with writing it and b) set up a more formal and consistent way to get the draft of it out there. let’s see how the rest of the year goes!

Not much of an answer, but thank you so much for the enocuragmeent and kind words 😀

Any details on the IMC Leeds play tests? Can we sign up for it somewhere?

well, it’s usually more “turn up” than “sign up”! I’ll put a call out on Bluesky closer to the time, and if too many people are interested for a single session then I’ll happily run more than one.

That said, the easiest way will be to come to the MAMG roundtable on the evening of Tuesday 02 July, and I’ll gather players there to run a game afterwards 🙂

Looking forward to seeing you!

Great work, Thom!

I’ll start with same question I asked Andreas yesterday: any chance you have an expected release date for the game? I REALLY want to try this out. (EDIT: Mariana beat me to it!)

As for your question at the end of the paper: personally, I think that if we’re modeling an interaction as a ‘duel’ or a ‘clash’, we’re already metaphorically framing it as a kind of combat. Last week, in a gaming convention, I came across an indie TTRPG that did exactly that. According to the dev, all encounters were called “challenges” and could be “answered” with the resort to any skill. E.g. if someone pulled a knife on you, you could theoretically “win” the challenge by singing or dancing.

On the surface, it seems really avant-garde, but one could argue it’s just combat by another means (and with another name).

Now, a question of my own: how intertwine you think ‘violence’ and ‘combat’ should be? “Violence” is a very culture-sensitive concept (I presume the lombards didn’t consider ‘microagressions’ to be one, for example). And combat can likewise be perceived as non-violent.

Hello Vinicius,

Many thanks for your questions and interest – for the potential release date, I’ll have to point you to my (non answer) reply to Mariana as well, progress is slow but I’m going to try and make it at least a bit more ‘steady’ through the coming year…

I agree entirely about how terminology can model these interactions as violence, but definitely appreciate the flip side of that which you have drawn attentio to: One of the great joys of the TTRPG, i think, is the way that other players can and do find multiple, unexpected ways to respond to various situations. often situations which as a storyteller/gamesmaster (or “judge” for LangobardRPG!) you were certain only had one or two simple and straightforward ways to resolve them. And, yes, sometimes the most unexpected skill can be a viable response 🙂 But to use your example, I think it comes down to the rule set, whether we see dancing in these situations as being fighting by another name, or the opposite, and fighting is just dancing. Rules and language can definitely shape how the game and setting is experienced, both in game and in table chater!

As to your own question: yes, that question of what constitutes violence is definitely culturally defined. I’m going to have to come back to the question of miroagressions, or at least insults in the future, i think. A number of the laws deal with calling a woman a striga [something like a witch/vampire] and the insult is framed and redressed in comparable terms to an assault. they might not see it in terms of microagressions, but with a sideways glance, there’s arguably something comparable there. As I say, I’ll need to return to that in more detail one day. hopefully soon.

thanks for the question and the interest!

Hi Thom, that is a very bright approach to this broad matter that is violence in medieval-fantasy games !

Working on bandits in TTRPGs and video games, the use (and abuse) of violence in these settings has caught my attention, and I’ll sure be checking Albom’s paper !

Your conclusion about the false dichotomy law-violence is also very interresting, as what is often seen as the most chaotic and sociopathic behavior (attacking and killing NPC’s) is often the part that is most codified in the rulebook. My guess is that a system inspired by Lombard laws that blurs the line between laws and violence works perfectly fine in a world where the NPC’s – even the roughest bandits – are considered as social beings, part of a community. But many TTRPG, starting from DnD, do not actually consider ennemies – bandits most of the time – as humans : the laws are made to enable unrestricted violence against people that do not fall under the “normal” law.

Have you checked the rules for the One Ring’s TTRPG ? Not only the setting is inspired by early medieval era, but also the rules for combat are an interristing take on these type of laws : combat is not encouraged except against monsters, and attacking or killing humans is very often punished by the lose of Hope points.

Do you have any exemple of other TTRPG’s set in the early medieval era ?

Hi Albert, many thanks for the questions, and the kind words!

Here’s the address for Albom’s paper, enjoy! https://journals.uu.se/IJRP/article/view/281

Yes, you are definitely right about the social and community element in the Lombard laws (and other medieval law-codes), and one of the sanctions that comes through for certain crimes is selling the perpetrator into slavery and outside the provincia [region, or possibly country] – so there’s a sense of in-group/out-group being constructed there. But, yes, the construction of people whome violence can be legitimately enacted against – in early medieval law and in TTRPGs – is a fascinating subject, and definitely needs to be evaluated critically. and i think will defintiely benefit by being read in relation to each other.

I don’t really have a list of early medieval themed TTRPGs to hand, although i keep meanignt to croud source one. And alot of the ones I do have are supplements to other games (I used to have the viking themed expansion to Vampire: The Dark Ages, for instance, and Cthulhu: Dark Ages is set in the tenth century…)

Many thanks for the question,and for the suggestion of the One Ring TTRPG, it’s not one i’ve looked into yet, so shall definitelyadd it to The List of things to look at 🙂