Vinicius Marino Carvalho (Universidade Estadual de Campinas)

Historical agency is, once again, a hot button issue. Developments like the climate emergency and advances in AI prompted many scholars into acknowledging potential non-human historical agents – and the consequences doing so for the discipline itself.

In medieval history, the two plague pandemics and “little ice ages” (LALIA and LIA) have become obvious actants for these new narratives. In addition to their direct effects, some scholars have suggested indirect links between their underlying natural phenomena, degradation of social ties, and violence.

What do history games have to say about this? Simulations of conflict and cooperation are not uncommon. Neither are narratives of social breakdown following scarcity, pestilence or catastrophe. But these stories, while poignant and cathartic, don’t usually do justice to the complexity of the issue.

Natural disaster” can be a dangerous term, because the measure of what constitutes a ‘disaster’ is a particular human qualification. The fall of an empire might be calamity for its ruling bureaucracy; not necessarily for the non-human entities it exploited (or, for that matter, the human ones). Conversely, many people don’t see the industrial society they live in as a dystopia, even though it was built on ecocide and increasingly makes us vulnerable to extreme weather events.

History games (and games in general) often have trouble representing these values systems, tending to overemphasize quantifiable outcomes and offer a “fantasy of moral clarity”. As Chang argued, even seemingly harmless actions betray these biases. E.g. to explore often means to “brave” a new world in a predatory or self-serving manner. Cases like “Pentiment”, in which the avatar ‘explores’ a pre-known community, are not the norm.

However, games can be useful as thought experiments, pushing these contradictions to the limit. They can help us “practice our agential fluidity”: the capacity to take up and reflect on multiple disposable in-game ends.

True to Anthropocenic anxieties, in the Nier series our avatar “acts” within a world in which distinctions between humans and non-humans, [social] norms and [natural] causes, have become mudded. The people of Façade are a parable of this transformation.

Immediate conflict (humans V shadows; androids V robots) is revealed a distraction, its stakes meaningless considering larger ontological discoveries.

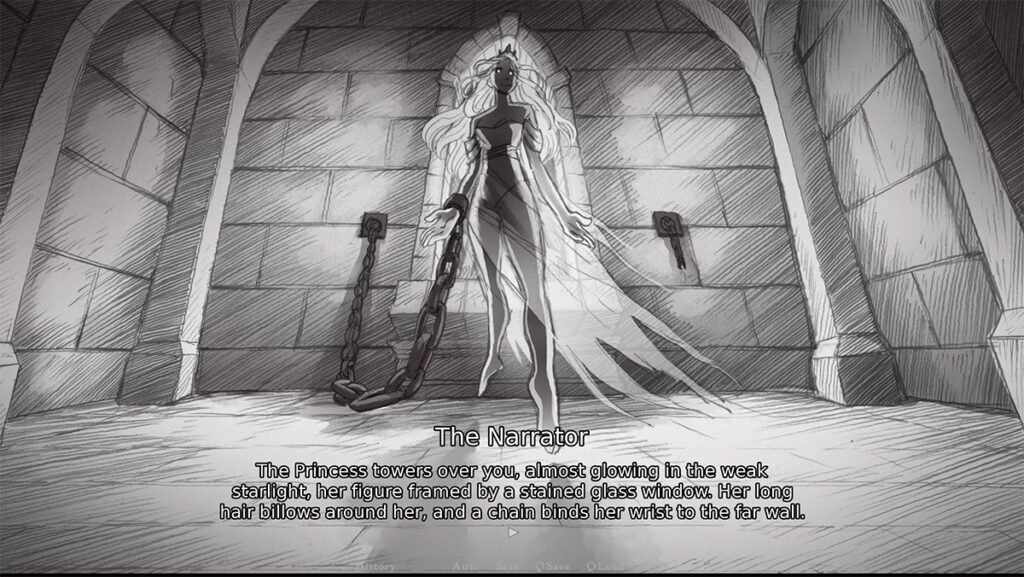

Following recent trends in fantasy writing, Slay the Princess uses court intrigues and medievalist trappings as a mere subterfuge to help us make sense of a story entirely populated by cosmic beings – not unlike, perhaps, how we historians try to make sense of nature by including it in pre-existing narratives (e.g. “The 14th Century Crisis”, “The Great Divergence”), however much these models are indebted to an anthropocentric view of time.

Nier and Slay the Princess remind us of the “perpetually changing set of social, symbolic, ontological, and material relations through which historical actors – human and nonhuman – are co-constituted”. Relations which can not merely explain social strife but also (if we’re willing) help recontextualize it altogether.

Thanks very much for this Vinicius, this is a really interesting approach and it’s not something I’ve really thought about previously. Could you expand at all on how you think the different endings and moral ambiguity of games like Pentiment or Slay the Princess could be used to explore history? And is this something particularly pronounced with medievalist games? Or do we see examples in games within other settings?

Yes! I’m finishing work on a paper about “Slay the Princess”; I’d be glad to share some thoughts about it. (I’ll get to Pentiment on a second comment).

On its surface, the game feels like your usual postmodern, character-vs-author, I-make-my-own-truth metanarrative adventure, in which the avatar (an assassin hired to kill a Princess) rebels against the narrator, and the world starts going haywire as a result.

We also inevitably “lose” at the end of each game loop and are brought back to the beginning (with the knowledge of what came before). And, by trial and error, we eventually find out our actions shape what the “Princess” turns out to be. E.g. if we decide to kill her, she becomes a threat. If we show mercy, she becomes an innocent victim. Inconsistent combinations of actions produce unexpected and hilarious results.

Eventually, we find out “we” are not an assassin, but the World itself. Likewise, the “Princess” is no princess, but a personification of Change. The conflict we lived through was, thus, a metaphor for the dialectic of change versus continuity.

The game does something we very rarely see (in any medium): it doesn’t just question *a* history, but (human) History itself as an adequate lens to understand time and change. Tellingly, once we realize this is not a human story, we understand there is no contradiction, no “multiverse” in the loops we performed: it only seemed contradictory because our linear conception of time is limited (like trying to imagine a new color).

I don’t think what makes the game great has anything to do with medievalism. On the contrary, I think it succeeds *precisely* because it thinks outside the box of historical periodization (I’ll talk more about that at Leeds!).

Indeed, the closest comparison I can make with it is the novel “Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruin of Ymr” by John Crowley – which is, itself, an exploration of more-than-human understandings of history.

(I haven’t looked it up, but I’m PRETTY sure the Slay the Princess authors read that book. Ka’s protagonist is a crow; so is the assassin (and the Narrator).)

Now, for Pentiment: it’s a much more traditional narrative – consequently, so are the historical ideas within it. But, speaking of the multiple endings and its moral ambiguity, in particular, I think it does a great job immersing us in a pre-Sattelzeit world (cf. Kosselleck). These people were not medieval or modern; they inhabited a different regime of historicity in which, unlike us, they weren’t cut off from their own past by a sense of progress and acceleration. And, consequently, had a very different relationship with the very need to periodize things.

I like the fact that the game never spells this out for us, as if it is inviting us to make our own judgments about it (Blair’s paper on the game in last year’s conference touched upon one of its rhetorical tricks). History aside, I think this is great game design, as it avoids the “banality of value” Miguel Sicart and Thi Nguyen criticize so much in games – i.e. we are not “punished” or “rewarded” for choosing the right or wrong morals. Consequently, we don’t (and can’t) condition our actions to maximize a given outcome.

Thanks so much for this Vinicius. I know I’ve expressed my personal dislike for Pentiment’s ambiguity previously (particularly with regards to its limitation of options to the player), but I can absolutely see how it (and Slay the Princess) provide interesting deconstructions of narrative and historical approaches. I’ll have to have a think about if this would work in the classroom… Do you have any thoughts?

Indeed, having all but “platinum-ed” Pentiment, I see what you mean by the lack of player options. I should probably also clarify that while I think some ambiguities work, others feel like a cop-out (e.g. the killer’s enabler having no fixed identity, the choice of murals having no explicit payoffs beyond the ending cutscene, the lack of consequence for asking the musicians to sing a Protestant hymn at a Catholic celebration…)

As for classroom, I have used Pentiment twice – in both cases, in classes about temporalities & periodizations. In addition to the points I outlined above, the game brings up some interesting examples of how our perception and relationship with time changed with the advent of modernity. Notably, the introduction of the mechanical clock in the third act, which reestructures the whole social life of the village.

In my Games & History class, specifically, I analyzed it alongside Heaven’s Vault, which also examines the issues of temporality and historicity, although in different ways.

“Slay the Princess” I haven’t used before, but I reckon it should be even easier to work with, being a much shorter and simpler game (which is also available DRM-free). The whole visual novel is also available on YouTube – so players can check different outcomes without having to replay the game.

I plan to organize my next Games & History course around topics in historical theory. I think I’ll probably assign it to a class on agency (which is the theme of my forthcoming paper, and also something the game does particularly well, game design-wise).

Thanks Vinicius! I’ll see if I can use Slay the Princess next year, you’re right: the short playtime will be really useful in class. I also look forward to reading your paper!

[…] Cooperation, conflict, and more-than-human agencies in medieval games – Vinicius Marino Carvalho (State University of […]