By Benjamin Dorrington Redder (Ritsumeikan University)

Fictionalisations of history within Japanese historical video games constitute a distinctive style of representing the Medieval past in contrast to the more commonly researched fictionalisations within games set in Europe and North America. A close inspection of Japanese historical games reveals a larger array of fictionalised representations, including ‘rekishi monogatari games’ as a relatively understudied group of Japanese history games that recontextualises Japan’s past in the form of ‘monogatari’ historical tales. In practice, these games represent Japanese history by remediating the representational conventions, content, aesthetics, and cultural motifs from Japan’s monogatari traditions of historical/cultural storytelling, entailing literary, oral, visual, and performative sources. The primary value of these remediations is dissemination of experiences that playfully re-examine and/or challenge both past and contemporary re-tellings, receptions, and recognitions of Japan’s past.

The game Nioh (Team Ninja, 2017) is chosen as an exemplar late Medieval rekishi-monogatari text. Nioh re-contextualises the life of the Englishman and first European samurai William Adams (c. 1564 – 1620) during the last years of Japan’s Sengoku (Warring States) period (1476 – 1603) as an individualised warrior tale in a dark historical fantasy style. The monogatari conventions are present in many areas, two of which are chosen for illustrative discussion. Namely, Nioh’s fictionalisation of the player’s protagonist Adams as a warrior hero and yōkai hunter constitutes a recent addition to Japanese warrior protagonists (e.g. Minamoto no Raikō, Minamoto Yoshitsune, Taira Kagekiyo, Jiraiya) recounted in monogatari histories, legends, and creative adaptations across Medieval and post-Medieval eras.

As an opportunity to create their own version of Adams as a monogatari warrior hero, the player is able to collect, choose, and/or wear or use many types of attire and weapons pertaining to the samurai, ninja, or onmyōji (specialists in magic and divination) professions.

Figures 1 and 2. William Adams wearing Karakawa armour worn by samurai Taira no Sadamori from the tenth century (left), and youngblood armour (right) shown in the trailer and promotional artwork.

Moreover, the combat system consists not only of Adams engaging in Medieval melee and ranged combat akin to the Sengoku samurai warrior (including access to unlocking melee weapon skills or arts), but also the opportunity to use and unlock new ninjutsu (ninja) and onmyo (magic) arts. In discussing onmyō arts further, this element ranges from offensive (e.g. elemental magic) and defensive spells (increased temporary protection again weapon damage), with the action to cast this spell usually depicted by Adams performing a mudra (hand gesture). This combative aspect is a remediation of samurai heroes employing both physical and magic (mudra techniques or talismans/scrolls) in defeating supernatural entities as evident in tales (e.g. Onzōshi Shimawatari, and Kagekiyo).

Figures 3 and 4. William Adams’s activation of the ōnmyo spell by a mudra gesture (left), and then performing a fire ball shot, a type of fire elemental ōnmyo spell (right).

As a yōkai hunter, Adams fights not only human combatants but also yōkai (supernatural entities) that plague Japan. Among the yōkai encountered are a number of game bosses usually encountered at the end of the main mission. These yōkai entities are re-constructed from a combination of literary, oral, and/or performative sources based on warrior monogatari tales, folklore, and drama plays (e.g. Shuten-dōji, Tsuchigumo, and Tawara Tōda Monogatari).

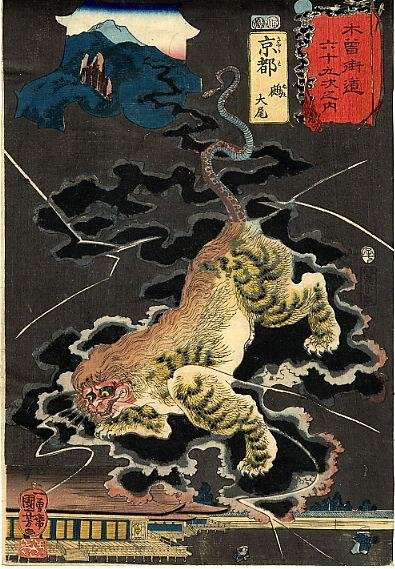

Figures 5 and 6. Nue creature within Mt. Heizen (Mt. Hiei) near Kyōto. The Nue is primarily remediated from descriptions (Tale of Heike), and visual depictions (e.g. Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Ukiyo-e woodblock print ‘Kyoto Nue Taibi’).

Figures 7 and 8 – A depiction of Hattori Hanzō II (Hattori) Masanari revived as an ōgama (giant toad) yōkai, alluding to Edo period kabuki depictions of ninja magically shapeshifting into a toad.

Examining re-contextualisations of monogatari Japanese warrior heroes illustrates some of the material, folkloric, and poetic literacies about the Sengoku period and post-Medieval receptions of that history in Nioh.

Images:

Image 5: Wikipedia. (2006, 10 March). Kuniyoshi Utagawa, ‘Taiba (The End)’, 1852 [Image]. Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kuniyoshi_Taiba_(The_End).jpg

Image 7: Wikipedia. (2012, 28 January). Hattori Hanzo from the 17th century [Image]. Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hattori_Hanzo.jpg

Self-Authored Screenshots:

Figure 1: Redder, B. (2025, 28 April). Episode 11 [Footage Screenshot], min 2:24:22.

Figure 2: Redder, B. (2025, 16 April). Episode 4 [Footage Screenshot], min 24:02.

Figure 3: Redder, B. (2025, 17 April). Episode 5 Part ii [Footage Screenshot], min 12:54.

Figure 4: Redder, B. (2025, 17 April). Episode 5 Part ii [Footage Screenshot], min 12:54.

Figure 6: Redder, B. (2025, 25 April). Episode 9 [Footage Screenshot], min 43:22.

Figure 8: Redder, B. (2025, 24 April). Episode 8 [Footage Screenshot], min 1:16:04.

Thanks for the paper! You discuss at the start of the paper how these sorts of stories can re-examine or challenge elements of the past. Could you expand a little more on how William and his presentation challenge older Japanese perceptions of the medieval period? Clearly he adds to the ‘hero roster’, and is bringing in some European elements (besides his name, there’s all the very obvious Witcher influence going on here), but I wonder what if anything that really challenges about Japanese historical perception.

Hi James

Thank you for your interest and questions on this paper. On a broad level, Nioh’s inclusion not only of William Adams but also on a secondary level settings, historical figures, and other references based in late sixteenth-early seventeenth century Europe (re-imagined within the fidelity to the monogatari tradition of fictionalising the past) illustrates the viability of incorporating foreign referents and experiences in Japan during the Sengoku period with that of the more numerous Japanese Sengoku constituents. Consequently, this creates a thematic presentation that, while ficitonalised in the monogatari form, is grounded on the globalised, interconnected character of Sengoku Japan to the outside world before the Sakoku (limited/controlled contact) policy in the mid-seventeenth century in contrast to the internal, domestic constructions of Sengoku history and its military conflicts which are more common in historical games of this period.

On another textual level, one of the things I am currently interested in with Nioh for my research is trying to discern why Team Ninja opted to choose a European historical figure (instead of the more obvious choice of a notable Japanese historical figure of that time), as one of their principal mediums for re-telling Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama history (including the battle of Sekigahara, one of the main missions within Nioh) in a more darker, sombre manner. From my current standpoint, I would say in this case that the challenges or re-examinations stem less from William Adams himself and his European background. Rather, it is more to do with how Adams serves as a vehicle for players encountering historical figures, referents, and events from the Sengoku period that problematise or at least bring to light insights contrastive to past popular images or representations of that same history, but of which are largely unknown outside academic Japanese history studies, or have received limited academic scholarship.

Thanks so much for this paper, I’m not very familiar with Japanese historical games so this might be a silly question, but it’s interesting to me that the game chooses to use an historical Englishman who became a samurai as the main character rather than a Japanese warrior like those other examples you listed here – how does this game and its English protagonist fit into the general trends in these games that adapt monogatari texts? And how do you think that relates to its reception (whether big or small, I’m not familiar!), especially amongst western audiences?

Hi Tess

Thank you for your interest in this paper. Your first question is interesting, and I think there are at least several answers to this one. I would love to give this an extended explanation, but one that comes to mind is that Nioh fits within the action/action-adventure (e.g. Ōkami, Genji: Days of the Blade) and horror game (e.g. Kuon) systems which currently make up the largest subset of monogatari games, although its possible the RPG and/or open-world systems would provide a viable expansion to this subset of Japanese historical games. However, the Nioh series (including yesterday’s announcement of Nioh 3) stands as an interesting case from most of the early monogatari games, in that the game studio Team Ninja seems to work very closely not only with the typical historical sources (the visual and material asepcts of the Sengoku era), but with the myriad of historical folktales, legends, and dramatic adaptations. For instance, yōkai are, for the most part, either closely re-constructed to the minute detail from several or a collection of sources with minor liberties or changes (such as the Nue), or in other ways are new variations from a combination of several sources in re-casting historical figures into yōkai beings (such as Oda Nobunaga’s wife Princess Nōhime who comes back as a yuki-onna).

In other ways though, the re-contextualization of William Adams as a warrior protagonist definitely stems from Japan’s poetic conceptions of the warrior hero tales alongside Japanese cultural trends in game design, resulting in a ‘Monogatari’ William Adams that is some ways related to, but in other ways distinct from the ‘real/record’ William Adams. I was not able to address this in the paper, but in Nioh, while parts of his life in Japan are generally followed from the known record, Adams is portrayed not as the Englishman born in ‘Gillingham, Kent’, but as an Irishman who formally served England as a privateer and was a survivor from the Nine-Year’s War between England and Ireland who were in rebellion. He also has his own spirit guardian called ‘Saoirse’ based on Gaelic folklore which is stylised in the Japanese conception of ‘Nigitama’ (gentle spirit), and her capture by one of the main villains ‘Edward Kelley’ is the primary reason for Adams journeying to Japan. You can see how Nioh’s version of Adams, while certainly removed from the background of the record Adams, becomes a Japanese source for making new monogatari expressions and models of warrior archetypes based on threading and re-configuring some of the European historical events, referents, folklore, and themes/motifs into its wider Sengoku monogatari story.

Your second question is also interesting. I wish I could give this a full answer, but I am still investigating this area as there are so many monogatari games (particularly older ones) and would hence have to dig deeper into what players thought about them! I was not able to address this point in the paper, but my current postdoctoral research into gameplay representation within rekishi monogatari games addresses them under several layers. Namely, how they work as multimodal gameplay histories within the context of Japanese monogatari history (representation), as game systems (proceduralism), and as game media products (orientational media).

From what I can gather so far in the case of Nioh, the reception by western players via forums has certainly been at least of two camps, a discussion on the history depicted in Nioh, and the ludic reception of the game from being a historical version or successor of the souls-like game genre to becoming its own distinctive form from the Souls series when Nioh 2 was released in 2020. With the lore camp, most of the discussions have stemmed around the material/military history of the Sengoku period, and that of William Adams (including the studio’s choice for him as the protagonist of the first game and in other ways helping other players understand who this historical figure is). Recently William Adams has been a foil within game media discourse by certain players surrounding the recent Assassin’s Creed: Shadows inclusion of Yasuke (albeit in ways that I do not agree with as I think Ubisoft and Team Ninja conceptualised their inclusion of foreign characters in different ways, the former in the realm/style of realist-fiction and the other primarily in historical fantasy). Interestingly, there does not seem to be a lot of forum discussions on the lore-based analysis or dissection of the yōkai representations beyond broad descriptions or (within the ludic realm) how-to-defeat boss guides, such as the ogama (giant toad) boss fight to name one. This limited area stems I think from a continuing discourse by western audiences of the fact-fiction binary construction, as in the languages of fiction are opposite to the conventions and principles of history rather than constituting another language of historical representation with its own conventions of historicity, fiction, and referentiality (such as the historicity of the fantastical monogatari form of Japanese history in rekishi monogatari games). Therefore, I think the historical lore of the game’s fantastical elements (including Nioh’s combat system) pertaining to the monogatari style is not well-covered in western audience receptions of unlike say the parallel and/or mythological game worlds such as Elden Ring and the wider Souls series.

I hope I have answered these respective questions, but please let me know 😊