By Lucas Haasis and Patrick Heike (Gamelab ‘Villa Geistreich’ in Oldenburg)

Pentiment is a narrative adventure and crime game set in 16th-century Bavaria. It has attracted considerable attention from the gaming community, the media, and academic circles, primarily due to its vivid, detailed depiction of everyday life and the sweeping changes of the era.

The game is based on meticulous historical research and brings to life a period often overshadowed in public perception by the Middle Ages: the threshold to the Early Modern Period, characterized by the Reformation, the Peasants’ War, and profound societal transformation.

Pentiment offers significant potential for educational use, enabling learners to actively experience epochal change rather than merely passively reading about it. Players are confronted with moral dilemmas and social conflicts – such as those arising from tensions within the estate society, religious upheaval, or gender roles.

Through these interactive experiences, historical self-efficacy becomes tangible: learners gain insight through play into how change occurs and how history is shaped by individual actors – artists, clergy, printers. This microhistorical approach can be effectively combined with the analysis of primary sources in the classroom.

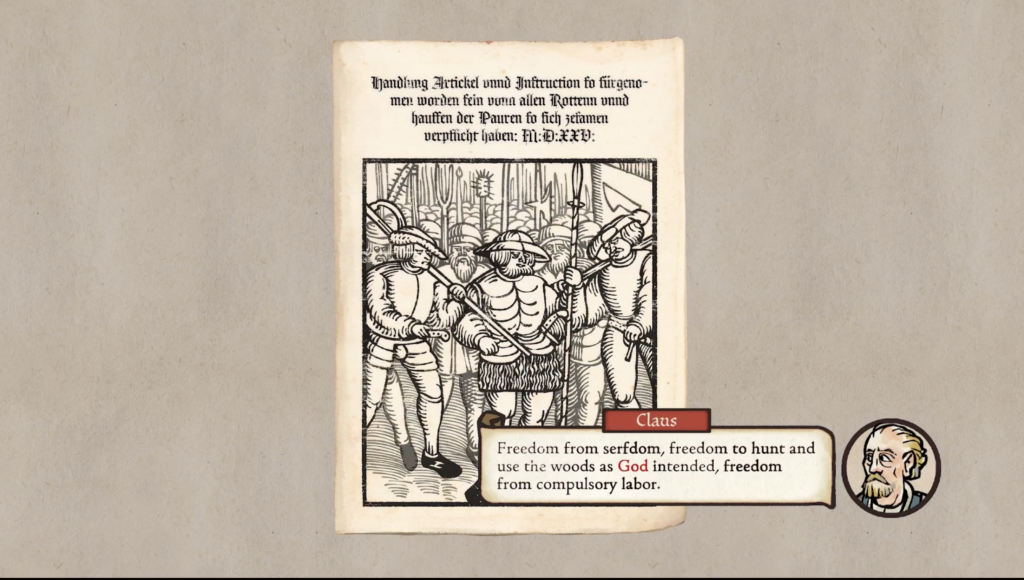

A salient example is the Peasants’ War: while many students have limited prior knowledge of this conflict, Pentiment allows them to experience the dynamics of uprisings and the complexity of revolution firsthand.

Encounters with the Printing Press and the “Twelve Articles of Memmingen” or discussions about human rights can thus be compared both in-game and with historical sources.

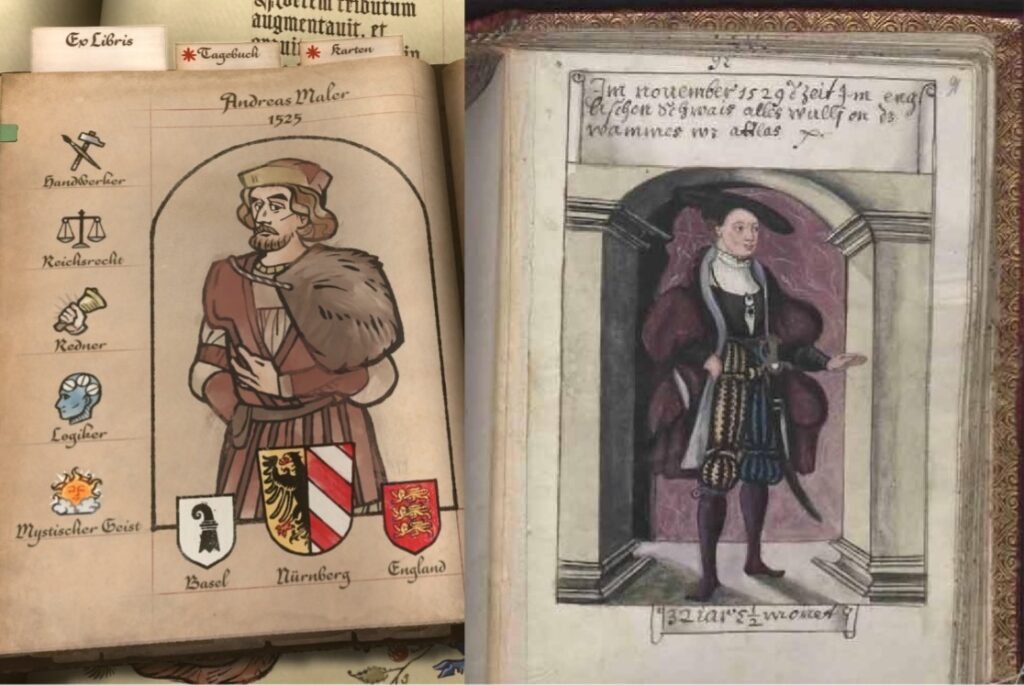

Social mobility is also illustrated, for instance, through the protagonist Andreas Maler – whose journey from journeyman to renowned artist mirrors historical figures such as Albrecht Dürer or Matthäus Schwarz, chief account of the Fugger family, who is sometimes referred to as the “first influencer” in history.

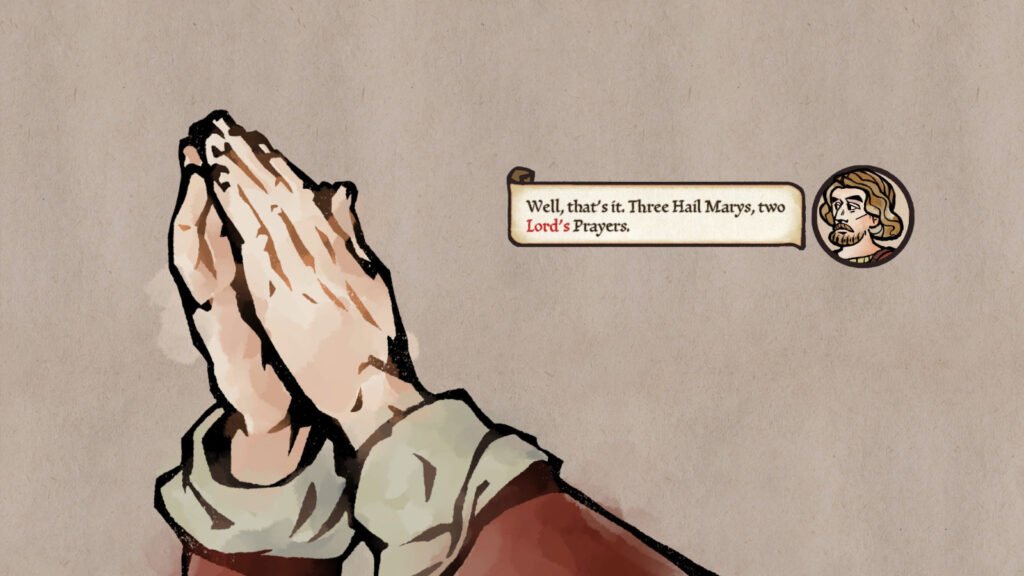

Another central theme is the Reformation from the intellectual world of Martin Luther to the role of the printing press.

The spread of new ideas becomes tangible as players participate directly in conversations and debates within ordinary people. The game demonstrates that history is shaped not only by “great men,” but above all by the dissemination of ideas and the actions of many.

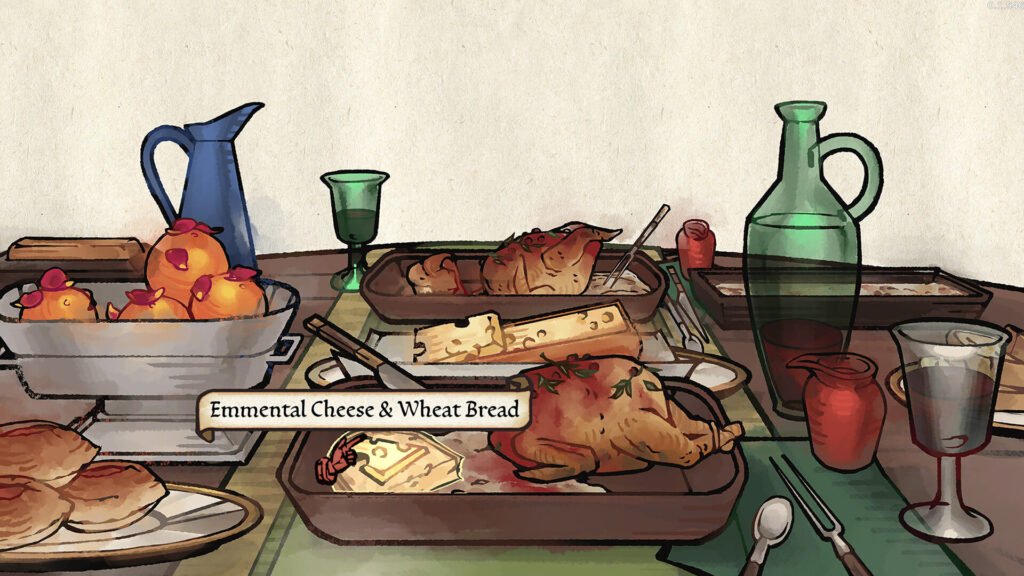

From a didactic standpoint, Pentiment is particularly valuable because it offers a low-threshold introduction to source criticism and the materiality of history. Learners interact with ruins, inscriptions, and manuscripts, analyzing them as historical sources. The game’s sophisticated representation of language and script – such as different fonts for various social groups – offers inspiration for interdisciplinary projects.

For classroom use, it is recommended to focus on playing selected scenes or utilizing Let’s Plays, combined with analysis on historical sources and discussions on social roles, media change, and societal transformation. Although Pentiment was not developed for educational purposes, its immersive, multi-perspective narrative style and the integration of gameplay with historical reflection create new opportunities for historical learning.

All images: Courtesy of Obsidian Entertainment. Thanks to Shyla Schofield and Josh Sawyer.

Homepage Gamelab (in German): https://uol.de/villa-geistreich/projekte-geschichte/digitale-spiele-in-geschichtswissenschaft-und-unterricht

Documentary (with English subtitles): Seminar: Playing in history lessons at University of Oldenburg: https://youtu.be/u-OhIkaihhs?si=F5S5b45bYtazgkV1

Read more:

Beek, Alan van, Aurelia Brandenburg und Lucas Haasis, eds. (4 September 2024). Zeitenwende. Interdisziplinäre Zugänge zum Spiel Pentiment. Mittelalter. https://doi.org/10.58079/128we.

Haasis, Lucas (4 September 2024). An Epoch on the Rise. On ‘Pentiment’, the Early Modern Period in Games and Microhistory. Mittelalter. https://doi.org/10.58079/128wi

Winnerling, Tobias (4. September 2024). Das Tänzeln auf der Epochenschwelle. Mittelalter. https://doi.org/10.58079/128wj

Wright, Esther. “Layers of history”: History as construction/constructing history in Pentiment. ROMchip: A Journal of Game Histories 6 /1 (2024): 191, https://www.romchip.org/index.php/romchip-journal/article/view/191

Recommended Videos:

Interview with Josh Sawyer: Alan van Beek and Lucas Haasis, Interview and Q&A with Josh Sawyer, Game Director of ‘Pentiment’, 2023, DOI: https://doi.org/10.26012/mittelalter-31324

Watch the keynote “Illuminating Those Who Illuminated Me. Micro- and Macrohistorical Sources for Pentiment” by Josh Sawyer, Studio Design Director at Obsidian Entertainment, Oldenburg 2024.

Watch Noclip – Video Game Documentaries. The Making of Pentiment – Noclip Documentary. Video. YouTube, 9 April 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffIdgOBYwbc&t=1818s

Pentiment is available for Windows, PlayStation, XBOX and Nintendo Switch: https://pentiment.obsidian.net

Recommended further reading:

McCall, Jeremiah. Gaming the Past. Using Video Games to Teach Secondary History. Second Edition. New York/Abdingdon: Routledge, 2023.

Houghton, Robert (ed.). Teaching the Middle Ages through Modern Games. Using, Modding and Creating Games for Education and Impact. Video Games and Humanities 11. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2022.

Preisinger, Alexander. Digitale Spiele in der historisch-politischen Bildung. Frankfurt am Main: Wochenschauverlag Geschichte, 2022.

Haasis, Lucas. Games im Geschichtsunterricht. Handreichung zum Einsatz von Games im Unterricht. Themenportal Let’s Remember. Games–Erinnerung–Kultur, 2024.

Levi, Giovanni. “On Microhistory.” In New Perspectives on Historical Writing, edited by Peter Burke, 93-113. University Park, PA, USA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992.

Rublack, Ulinka. Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. “A 16th-century German accountant compiled a book of personal fashion that rivals today’s Instagrammers in detail and dedication,” The Atlantic (November 1, 2015), https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/11/first-book-fashion-selfie-king/413047

Thank you for this paper, Lucas and Patrick. The use of video games for teaching is definitely one of the most important areas of enquiry when approaching digital gaming and its portrayal of the past. I was wondering if you have used Pentiment in an actual course. How did you use it? What would you emphasize when teaching this particular period? What type of assignments or exercises do you believe could be implemented in the classroom?

Hi Juan and thanks for your post! The game can primarily be used to make students aware that history is always a construct (in video games, in movies, but also in contemporary sources we still have to interpret). The ability to ‘deconstruct’ is very important in German schools. So, we mainly discussed in class how history is ‘made’ in games using the examples mentioned in the post (students of all ages love Matthäus Schwarz …). The students have learned that the game presents them with historical images and certain ideas about the past rather than facts, and that games are always strongly influenced by different sources. We compared historical sources from that period with the representation in the game. We compared what they know about the 16th century with what is depicted in the game – and what they would have liked to see added (they are largely satisfied, but emphasise that they like the depiction of everyday life in the game best – how people dressed, what they ate, etc.). Last but not least, we usually include statements from the developers in our classes – which wasn’t too difficult this time, as Josh spoke very openly about his goals behind the game and his influences – on many channels. We are currently preparing teaching materials about the game for publication with two other colleagues. It is in German, but it may still be useful for some readers. So, finally, I would like to say: stay tuned!

Thanks for your brilliant paper! I would like to know if you already used Pentiment or segments of the game in your classes for example for teaching Early Modern History and could you share your gathered experiences and impressions in more detail? How do students react? Gaming situations in classrooms can quite differ (as I experienced it).

Another aspect concerns the presented historical perspective of Early Modern Germany (in this case, I assume) – is the depiction solely based on Germany/Holy Roman Empire? Do aspects of Reformation in other European parts occur (e.g. Bohemia, Poland-Lithuania, Englad, France etc.)? Does Pentiment only tell a one-sided story of social revolt/inequality etc. expressed through religious critique using Reformation and its ideas as a means or a trigger?

Hello Kristina, yes, we have used it with both school pupils (9th grade) and university students (history/prospective teachers). The reactions were positive in both cases. Last winter, I also gave the introductory lecture on the early modern period at the University of Oldenburg. It is a basic course, but I was able to incorporate the game into almost all aspects of the topics I covered about the 16th century, as well as in relation to the representation of history in popular culture, etc. The game helped me to illustrate certain aspects such as the estate-society, but also everyday life and rituals, etc. and also to show how microhistory works. In our game lab, we mostly use games about later eras (especially with regard to remembrance culture), but Pentiment allows us to focus on an era that young people are less likely to associate with games. As for the Reformation, the game primarily uses references to the Reformation rather than making it the subject of the game itself. Luther appears in dialogues, for example. Luther himself does not appear as a character. However, Zwingli and other reformers also appear in the dialogues, which I found very refreshing, as it acknowledges the fact that the Reformation was a movement that represented religious pluralism and was not a ‘one-man show.’ The next step is for students to research who these people are – this works well! And they learn something they didn’t really know before. As for the revolt: In fact, the revolt as depicted in the game is mainly connected to the history and narrative of the characters in the game, but the ideas conveyed in it establish a connection to the Peasants’ War. Important sources are also shown, and the games emphasises that religion, claims to power, everyday hardships and the printing press all played a role.

Thanks, Lucas! This is brilliant! Maybe I will also use Pentiment now in my University courses when teaching Early Modern History and embedding the gained knowledge into broader contexts like you explained here. Students always appreciate gamification in class 😉

Wonderful points, Lucas & Patrick–I especially appreciate your point about a low-threshold way into material analysis, as I think the way the game distinguishes between ‘Roman’ and ‘Christian’ is quite interesting, and is an excellent way to parse the tensions between the material past and present.

Thank you Blair – yes, I agree. Also religion in general is an exciting topic that the game raises! Especially because it is not portrayed in such a simplistic way (as other games do)!

Great work! Thanks for your paper! I loved Pentiment and was wondering: which scenes from the game could be used in the classroom to analyze the formation of social and cultural identities? Are there particular episodes that highlight tensions related to gender, class, or religion?

Thank you for this! I don’t know how I missed this game. I’m adding it to my playlist now!