Quinn Bouabsa-Marriott (University of St Andrews)

In Fire Emblem: Three Houses, the continent of Fódlan is divided by three nations: the Adestrian Empire; the Holy Kingdom of Faerghus; and the Leicester Alliance. Each nation operates with its own interests and set of internal problems. These are portrayed on a micro-level at the Officers Academy of Garreg Mach Monastery, an institution run by the Church of Seiros where students gather to train in military affairs. As one of the teachers, the protagonist chooses to lead one the school’s three houses: the Empire’s Black Eagles led by Edelgard; the Kingdom’s Blue Lions led by Dimitri; and the Alliance’s Golden Deer led by Claude.

Depending on the player’s choice the game proceeds to split off into a number of different routes. Although each route follows a broadly similar sequence of events, fighting in a war declared on the continent by the Adestrian Empire, with each house fighting for its respective nation, how these events are interpreted by the player, as well as the surrounding cast of characters, will vary.

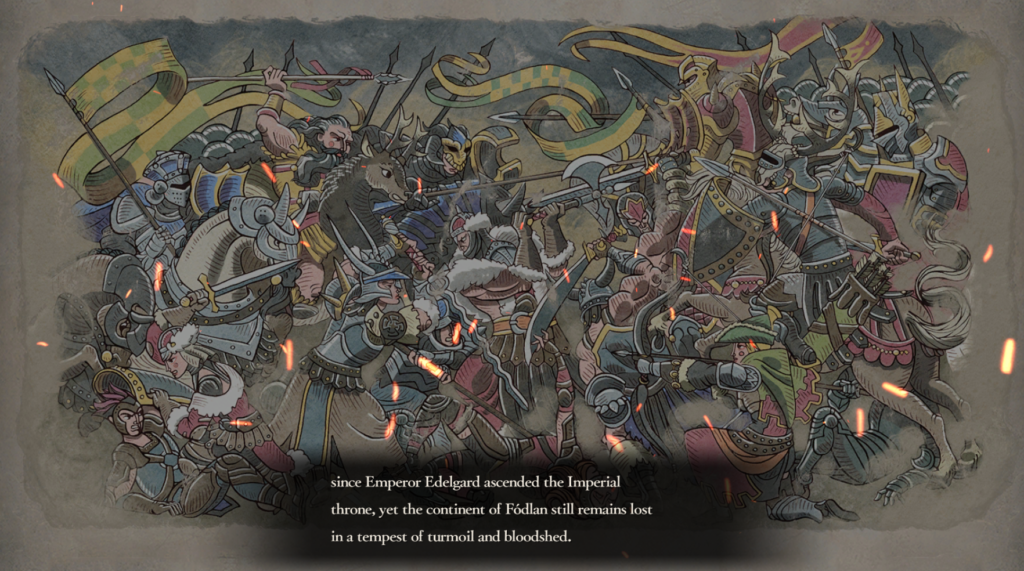

This leads us to consider Three Houses’ central theme and the subject of this paper, historical perspectives. Already, from the start of the game, the story unfolds in a chronicle format with each month opening with a retrospective run-down of events yet to unfold. Combined with its beautiful woodblocks, the game sets the scene for players to think of the ensuing conflicts in historical terms, as events of the past.

In the story itself, there is no dichotomy of ‘good vs bad’, only different historical agents, namely the house leaders, with their own competing aims and ambitions. The game shows no particular preference on any one house leader’s perspective, and it is left up to the player to decide which view they find convincing, which has been the subject of intense discussion online. It is what Kaya Yilmaz has termed ‘historical empathy’, by which we can understand the past through the “intentions and the actions of historical agents”.

Working with one of the house leaders to achieve their goals, the game introduces bias as a key element to how the story is presented, with no truly reliable narrator to tell the player what is and what is not true and showing that historical narratives can easily be shaped by political power and influence.

Akin to frameworks like “history is written by the winners”, this approach bears the same limitations that this only considers singular, superficial, perspectives. These can be divided clearly along each route: the Blue Lion’s support of the Church against the Empire; the Black Eagle’s support of the Empire against the Church; and the Golden Deer’s opposition against the Empire and scepticism towards the Church.

Albeit simplistic, it would be remiss to deny the success Three Houses has found in building an appreciation for storytelling that goes beyond binary conflicts with notions of ‘good’ or ‘bad’ and that allows players to simulate how historians might approach sources by incentivising information to be constantly questioned and re-examined. Placing historiographical themes at the centre of the game’s narrative opens the floor for historians and game designers, alike, to further consider how we can make sources and source analysis a bigger part of the gaming world.

Further Reading:

- Sky LaRell Anderson, ‘The Interactive Museum: Video Games as History Lessons Through Lore and Affective Design’, E-Learning and Digital Media, 16:3 (2019), 117-195

- Abbie Hartman, Rowen Tulloch, Helen Young, ‘Video Games as Public History: Archives, Empathy and Affinity’, Game Studies, 21:4 (2021) [www.gamestudies.org/2104/articles/hartman_tulloch_young]

- Dawn Spring, ‘Gaming History: Computer and Video Games as Historical Scholarship’, Rethinking History, 19 (2015), 207-221

Thank you for the paper, Quinn! I was always a bit sad reading MAMG papers about Fire Emblem, due to not having how to play the games. Now that I got a Switch, that’s no longer an issue xD

I’m intrigued by the woodblocks, which are indeed gorgeous. How are they integrated into the game and/or gameplay? You ended your paper mentioning the potential role of source criticism in gaming. Were you refering to these images, specifically?

Thanks for the question! So with the woodblocks, the game follows a calendar system (which ties into sorting time to do different activities across the school year, as the player character is a teacher) and at the start of each month, the game presents a new woodblock scene. These cutscenes mostly describe seasonal patterns that shift across the year, but they’re also accompanied by hints of what’s going on in the game: either within the academy or the wider political world. These only get more explicit as time goes on and will ultimately side with whichever route/choices the player goes with.

When I talk about the presence of narrative sources in Three Houses, I’m not referring to these scenes. They do clearly present themselves in a chronicle format but they don’t contain the sorts of conflicting narratives and voices that you find in the actual game (whether that be in in-game texts across the academy or pieces of dialogue from the cast and numerous other NPCs), which ultimately lead players to fundamentally question the state of the world and its actors. Despite that, I still felt that they were important to mention because, as I would argue, they play an important role in setting expectations for players to think about the events of the game retroactively, even as they are happening in-game, as events being retold from a future where the player and his companions have won and are writing ‘their’ history.

Thank you for the read! I called my son over (15, he’s a fire emblem fan) and he loved your piece as well. What you discuss here about how history is written from the perspective of the victors and the game has no preference for which house you choose reminds me of Dragon Force. My question is about the game’s narrative. With each house presenting a different narrative, all of them being of equal importance, value, and likelihood, is it worthwhile to consider which is the canonical narrative? Is it even worth asking the question? And if not, then how should we approach ludonarrative analysis of the game? Do we just focus on the purely mechanical as there is no one set story, do we tailor our inquiry to the story line we stumble into, or do we play through all possible scenarios to fully understand the scope of the narrative?

Thanks again for your paper!

This an excellent, and equally complicated, question! As far as I’ve seen from dev commentary, online discussions, and the game itself, there doesn’t seem to be an accepted ‘canon’. From my experience, the Golden Deer route seems to be the one that focuses the most on the Church’s secrets and the behind-the-scene antagonists, exposing the ‘truth’ of Fodlan. However, even that route is full of ambiguity and has potential for varied interpretation, so I think the search for a clear, golden, ‘truth’ is, ultimately, a wild goose chase for something that the devs never intended, even if you complete all the routes.

So I suppose my initial reaction was that it doesn’t really matter and that no, one, narrative the game presents is more correct than another. I still think the latter of that is true, but I think I’ve perhaps come to appreciate that, for the average player, ‘picking a side’ is an inevitability that is, in itself, fairly interesting to look at, and can tell us about how players engage with (and compete over) in-game narratives. There’s certainly value in taking in an overarching approach, as I’ve tried to do here, to look at all the routes layed out and see how the game sets up these narratives for its player, but I don’t take that as the average experience. Given how long the a single route is, most people will only ever do a single route, and so it’s also worth taking on a lense that considers how each, singular, experience shapes player perception of the wider game.

Hope that answers your question!

Thank you for this paper ! I always have thought about historiographical themes in more grounded video games such as The Elder Scrolls series or The Witcher, but I didn’t quite realized Fire Emblem Three Houses and the choice based stories also had these !

Do you think other installements of the Fire Emblem series contain these themes ? I’m especially thinking about the game before Three Houses, Fates, that also contains three main directions for the story but revolves way more around the conflict between two houses (the two base versions of the game), and the third one serving as a in-between neutral ending (the DLC Revelation).

This is definitely something I, myself, have been wondering but I haven’t actually had the chance to play any of the other Fire Emblem games yet. Three Houses was my first, and I’m definitely excited to see what the rest of the series has to offer in the way it tries to present political conflicts and its agents.