Homeira Baghbanmoshiri (Kobe University)

This presentation aims to explore the simulated chronotope within The Witcher game series from a postmodern perspective to discover its nature and its connection to the real. To achieve this aim I have used Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of chronotope[1] to analyze repeated patterns of time and space in The Witcher games.

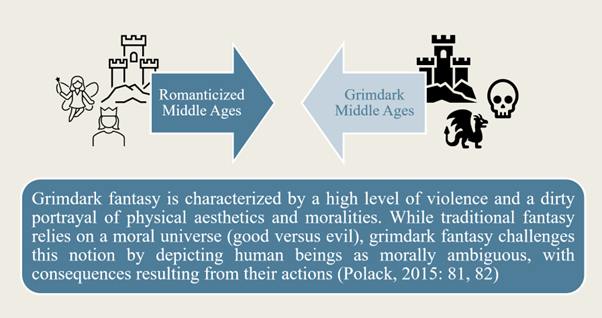

The Middle Ages have been a popular source of influence for creating alternative and fantasy worlds in Role-playing games (hereafter RPG). A game like The Witcher however, depicts a dark and grim image of these times. As Young explains, the genre that encompasses this style can be referred to as grimdark fantasy. According to Gillian Polack (2015), grimdark fantasy is characterized by a high level of violence and a dirty portrayal of both physical aesthetics and moralities of characters and the world they inhabit. Shiloh Carroll (2015) explains that authors like George R. R. Martin turn to grimdark fantasy to resist the romanticized portrayal of the Middle Ages. Martin himself claims that his books are “more realistic text, both historically and sociologically, than other neomedieval fantasy”, a neomedievalism[2] that he calls “Disneyland Middle Ages.” In essence, authors such as Martin believe that romantic medievalism is an escape from the harsh realities of the era, but they intentionally adopt a more realistic approach by depicting the cruel nature of the Middle Ages (Figure 1).

It appears that Andrzej Sapkowski, the author of The Witcher book series, aimed for a similar chronotope in his work, and the game adaptation has followed this sentiment by embracing the grimdark fantasy spacetime. Analyzing, the chronotopes in the game show that The Witcher aims to depict a medieval past in a manner that evokes a sense of realism. This emphasis on realism is achieved through simulating embodied history. decaying buildings and grotesque monsters contribute to the depiction of an existence of history in an otherwise artificial world while creating a dark and gloomy atmosphere (Figure 2).

Jean Baudrillard (1981) explains that in the post-modern era following the wars, people’s lives have become monotonous and repetitive. The sense of danger or violence is no longer present in daily life. As a result, people turn to the media, to experience and encounter violence. Baudrillard explains that cinema becomes infused with nostalgia, “to resurrect the period when at least there was history, at least there was violence (albeit fascist), when at least life and death were at stake.” Similarly, as part of the grimdark fantasy genre, The Witcher strives to create a game-world where players can experience violence and danger in a way that feels real.

[1] Bakhtin (1981) introduces the term “chronotope,” where “chrono-” denotes time and “topos” signifies space, to uncover recurring temporal and spatial patterns in novels. According to Bakhtin, time and space are inseparable concepts, and any text can be analyzed based on a series of spacetime continuums crafted by the author.

[2] Neomedievalism, as described by Young (2015), is a genre that references the Middle Ages indirectly. Since the Middle Ages is a distant historical period, our knowledge of it is based on surviving medieval texts and historical descriptions, leading to interpretations and perspectives that differ from reality.

Bibliography

Allan, S.: “When Discourse Is Torn from Reality’ Bakhtin and the Principle of Chronotopicity.” In Time & Society 3 no. 2, p. 193-218.

Bakhtin, M.M.: The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. 2nd ed.: University of Texas Press, 1981.

Baudrillard, J.: Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. University of Michigan, 1994.

Carroll, S.: “Rewriting the Fantasy Archetype.” In Fantasy and Science Fiction Medievalisms: From Isaac Asimov to A Game of Thrones. Edited by Helen Young, USA: Cambria Press, 2015, p. 59-76.

Cook and Becker.: “Video Essay: The Art of The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt”, 2022, [Online], [2024-01-30], Available at: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hNql4vqCN5E>.

Deterding, S. and Zagal, J.: Role-playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations. New York: Routledge, 2018, p. 34-61.

Gawroński, S. Bajorek, K.: “A Real Witcher—Slavic or Universal; from a Book, a Game or a TV Series? In the Circle of Multimedia Adaptations of a Fantasy Series of Novels “The Witcher” by A. Sapkowski.” In Arts, vol. 9, no. 4. MDPI, 2020.

Haynes, J.D.: “Bakhtin and the visual arts”. In A companion to art theory, Edited by Paul Smith and Carolyn Wilde, 292-302. UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Henry Jenkins, “Game Design as Narrative Architecture,” In Firstperson, 2004.

Huizinga, J.: Homo ludens, 1980.

James, E.: “Tolkien, Lewis and the explosion of genre fantasy.” In The Cambridge companion to fantasy literature. UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Juul, J.: “Introduction to Game Time,” 2004, [online]. [2024-01-30]. Available at: <https://www.jesperjuul.net/text/timetoplay/.>

Juul, J.: “The Magic Circle and the Puzzle Piece,” In Conference Proceedings of The Philosophy of Computer Games, 2008.

Majkowski, T.: “Geralt of Poland:” The Witcher 3″ between epistemic disobedience and imperial nostalgia.” In Open Library in Humanities 4, no. 1. 2018.

Mark, J. P.W.: “Inventing Space: Toward a Taxonomy of On- and Off-Screen Space in Video Games,” Berkeley: Film Quarterly, 1997.

Mark, J.P.W.: “Theorizing Navigable Space in Video Games,” In DIGAREC Series, 2011.

Netflix.: “Bestiary Season 1, Part 2”. The Witcher. 2021, [Online], [2024-01-30], Available at: https://www.netflix.com/us/title/81555915?s=i&trkid=254567369&vlang=en&clip=81557019.

Peterson, R.D. et al.: “The same river twice: Exploring historical representation and the value of simulation in the total war, civilization, and patrician franchises.” In Playing with the past: Digital games and the simulation of history, Edited by Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and Andrew B.R. Elliot. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013, p. 33-48.

Polack, G.: “Grim and Grimdark”. In Fantasy and Science Fiction Medievalisms: From Isaac Asimov to A Game of Thrones. Edited by Helen Young, USA: Cambria Press, 2015, p. 59-76.

Sapkowski, A. The Last Wish. 1993.

Schrier, K. et al.: “Worldbuilding in role-playing games.” In Role-playing game studies: Transmedia foundations. Edited by Deterding, Sebastian, and José Zagal. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Taylor, T. L.: “Pushing the boundaries: Player Participation and Game Culture,” 2007.

Tekinbas, Salen, K. Zimmerman, E.: Rules of play: Game design fundamentals, 2003.

Tychsen, A. Hitchens, M.: “Game Time,” in Games and Culture 4, no. 2, 2008, p. 170–201.

Young, H.: Fantasy and Science Fiction Medievalisms: From Isaac Asimov to A Game of Thrones. USA: Cambria Press, 2022.

Thank you for the paper! It made us review The Witcher – we have been a long-time fans of the novel, but have not played the game. We believe that the “grimdark” chronotope in the novel results from the fact that the novel is presented from the witcher’s perspective, and this is one character whose experience in life has been far from rosy. Our LARPing experience, which included two Witcher-based games (one of our case studies for our today’s video paper), confirms that the world of Sapkowski’s witcher can be interpreted in many ways, and not necessarily as grimdark. It is characterized by conflict and violence, but also by complex social interaction and negotiation.

Therefore, our question is to what extent the game developers’ interpretation of The Witcher’s world as grimdark aligns with Sapkowski’s original material?

(Edgar and Anastasija)

Thank you very much for the question. I agree that The Witcher should not be reduced to the idea of grimdark fantasy, and there can be many interpretations. But to answer your question, Polack suggests that while traditional fantasy relies on a moral universe (good versus evil), grimdark fantasy challenges this notion by depicting human beings as morally ambiguous, with consequences resulting from their actions. I think this theme is reflected in Sapkowski’s writings, with “The Lesser Evil” being a good example. However, the game takes this idea even further. In the game’s many side missions, players encounter stories from ordinary villagers who are not monster hunters or trained killers like Geralt. But their stories often end in tragedy and betrayal, and Geralt (or the players) are faced with an impossible choice that can result in the death of innocents either way.

Thank you for this – this is a really interesting theoretical framework to apply to The Witcher! I was wondering how you see this desire for violence balancing with the way players seek other experiences in the game too, I’m thinking especially of the way players take/share screenshots of the beautiful sunsets and landscapes? Do these go hand in hand or is there some tension there?

Thank you very much for the question. I think that the photorealistic environment itself can lead to more immersion, making the game and the violence feel more real. But I do agree that player behavior is always challenging the boundaries of what the game represents. However, there may not necessarily be tension between the two sides. I think the lighthearted fun that players find in engaging with the game world in novel ways can exist simultaneously as an experience of violence and darkness for those same players, without interfering.

Thank you for this paper – always good to see more Witcher discussion. Do you have any thoughts on the expansion Blood & Wine, and how it essentially combines the hyper-romanticised version of the Middle Ages on the surface (knights, chivalry, fairytale castles and gorgeous landscapes) with the grimdark version below the surface (all the violence, the class exploitation etc.)?

I’m just jumping onto your question, Markus, as I was going to ask pretty much the same one! I was wondering about your thoughts, Homeira, on how the depiction of Toussaint and even Skellige with their beautiful, romanticised, and to some extent stereotyped worlds can use the clash with the grimdark to tell stories of the Witcher universe?

Thank you very much for both of your questions. I must say that unfortunately I did not dig deep in to the expansion’s in my analysis. But to answer that right now, I think it is important to remember that Blood & Wine is in fact an expansion pack. Therefore, creators need to offer something that looks new compared to previously released content. I think this change is more due to the nature of postmodern media than the grimdark fantasy of the Witcher universe, despite the game’s attempt to maintain the underlying grimdark themes. In other words, the game has no choice but to include and combine different representations of the Middle Ages in order to stay fresh for the audience’s consumption.

I think an area that interests me with “grimdark” is the sense that in some ways it can actually lack punch compared to less grimdark settings, because you were *expecting* things to be bad already – whereas in a more hopeful setting, a dark moment can feel a lot more painful. Do you think there’s some useful things to be said about the importance of light moments in creating effective darkness in this genre? And maybe a differentiation to be made between a grimdark of light-and-shadows (which I think is something the most effective moments of the Witcher stories and games reach), and a grimdark where everything is more consistently grim (which is more where e.g. Warhammer 40K as an archetypal grimdark setting ends up, and I’d argue where the Witcher ends up in the moments where it’s being less effectively written).

Thank you very much for the question. I think the point you make is indeed a matter of good writing and good storytelling rather than the genre itself. To say that the genre of the game is grimdark is not to say that the game does not have fun moments. A good story usually has highs and lows at appropriate moments. However, depending on what kind of emotion the creators want to evoke, the approach can change. Having a setting that is not grimdark but leads to violence can be shocking. But playing a game that players know is grimdark creates suspense, where players expect something bad to happen, but don’t know when or where.

Thanks so much for this paper! I’m curious about your thoughts on the effect of Grimdark works, generally, on the public perception of the Middle Ages. Is there a sense that the gritty violence is more “accurate”? It seems Grimdark has (perhaps unintentionally) translated moral ambiguity into a cohesive aesthetic, but I’m curious to what extent it’s transformed all depictions of decrepititude as shorthand for this expanded morality without doing the narrative work (thus rendering it a surface aesthetic).

Thank you very much for your question. Please excuse me as I may not have understood your question correctly, but I hope this answer helps. I think grimdark fantasy claims to be a more accurate representation, but it is not. It may contain some truth about the Middle Ages, but to borrow from Baudrillard’s theories, it creates a simulacra that tries to replace the reality of the Middle Ages. I don’t think it’s purely aesthetic, and it brings its own narrative structure as well as its own gameplay mechanics (in the context of a game). However, it is not the only simulacrum of the Middle Ages that exists, and it has both influenced and been influenced by many different representations and simulations of the Middle Ages that exist simultaneously. The last point I mention is in regards to the idea of neomedievalism. Young points out that neomedievalism is “not a dream of the Middle Ages, but a dream of someone else’s medievalism. It is medievalism doubled up upon itself” (Young 2015, 2). This is to say that the grimdark fantasy depiction of the Middle Ages (as well as many other depictions of the Middle Ages in the postmodern era) is influenced by many earlier depictions, but it is different from them and has therefore lost its connection to the reality of that period. I apologize for the long answer, but I hope it was helpful.

Thank you for this analysis, it was very interesting. Especially thinking about my own game where I chose a more colourful and comedic tone for its medieval chronotope, specifically as a counterreaction to the grimdark works of Martin and Sapkowski, while still trying to avoid romantization. I guess we are always in an ongoing (Bakhtinian?) dialogue with previous works about how to present the past.

Thank you for your comment. It is, as you say, an ongoing dialog. I was just reading your article on The Knight & the Maiden. It has an interesting approach to depicting the Middle Ages. It seems that the game has received some influence from Japanese games, as you mention in the article. My original analysis is a comparison between The Witcher and the Final Fantasy series, and I think JRPGs have a similar approach to what you described. They are neither grimdark nor a romanticized version of the Middle Ages. They maintain a fun and comedic approach while tackling serious themes. So, if you do not mind, I wanted to ask you if JRPGs had any influence on the tone of your game.

“to resurrect the period when at least there was history, at least there was violence (albeit fascist), when at least life and death were at stake.”

This Baudrillard quote is timely, given how the claim of “realism” in fiction has often been used to justify an apologia for non-humanistic/illiberal/reactionary values. George R.R. Martin’s shameful comment on sexual violence comes to mind, but this can be found in political discourse more broadly (e.g. contemporary men are not “real” men; mainstream politicians are not “real” statesmen, etc).

I wonder if you have some thoughts on the role of these claims of realism within the fantasy genre? Many authors (Brian Attebery among them, IIRC), argue that fantasy emerged as a genre (as opposed to myths and other taproot texts) around the same time as realist sensibilities, circa the time of the industrial revolution.

There seems to be an inherent conflict between the two modes, maybe on an ideological, and not only figurative level. I’m reminded of Philip Pullman’s comments that “His Dark Materials” is not fantasy, but “bitter realism”.

Thank you very much for your interesting analysis. I agree with you on may points. The Witcher itself was not free of these discussions. The game was criticized for having all white characters, but then defended by some supporters who claimed it was a more realistic depiction of Eastern Europe during the Middle Ages. For a more in-depth analysis of this discussion, you can refer to the article by Tomasz Z. Majkowski (2018). As I mentioned in another comment, the grimdark fantasy claims to be more realistic but it fails. Not because it is fantasy but because the Middle Ages it depicts has lost its connection to a reality that has been lost for centauries.

I think that because fantasy is more complex in its current state than it was in its beginning, it is difficult to make a single statement about all forms of fantasy. But to answer your question, I think that both the audience and the creators of fantasy works need to be committed to a certain level of reality within the fantasy world. Otherwise, like many fairy tales, it will not be taken seriously and will be dismissed as a children’s story. This creates an ambiguity between the real and the fantasy, and therefore leaves room for the creators or the audience to bend that ambiguity to suppress the voices they don’t agree with.