Albert Leparc (Paris-Sorbonne University)

Hi ! For my second paper for the MAMG, I’d like to give a broad-brush approach on my research about the most common – if not the most common – enemy in video game RPG’s.

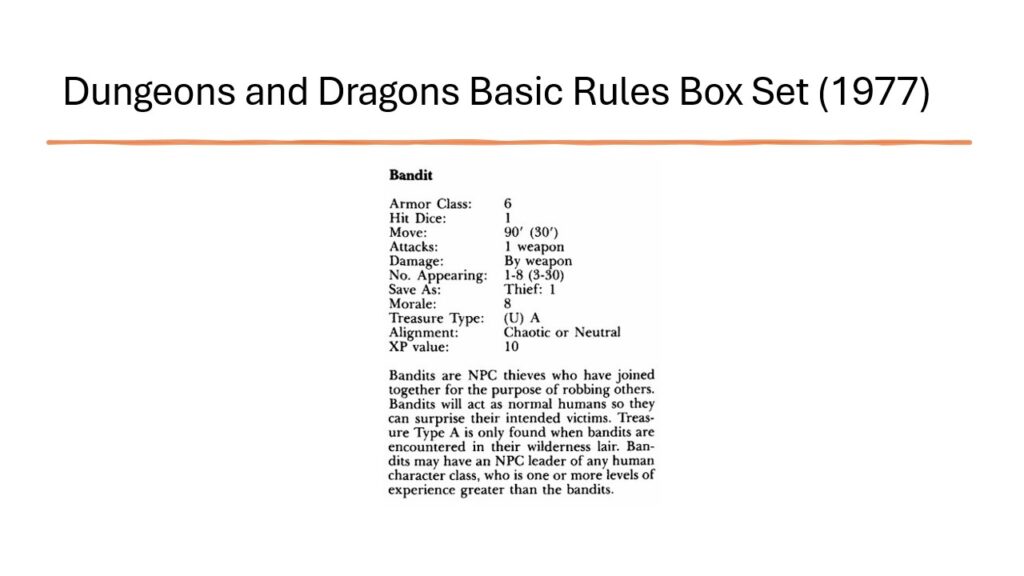

Since the 1st Edition of “Dungeons and Dragons”, “bandits”, “brigands”, and “thugs” have been taking the spotlight in the monster sheets and manuals. Serving as first level encounter, the most common factor we can find between them is their systematic hostile behavior towards the player, explained by their vague criminal background.

Videogames of course followed that path, as 1981’s Ultima used “Hood” and “Thief” as low-level enemies.

As Jaroslav Švelch analyzed, “The monster manual is, in fact, monstrosity squeezed into a database”. Including regular humans, with little to no magic abilities, alongside wolves or dragons can be surprising: were brigands that dangerous in the Middle Ages?

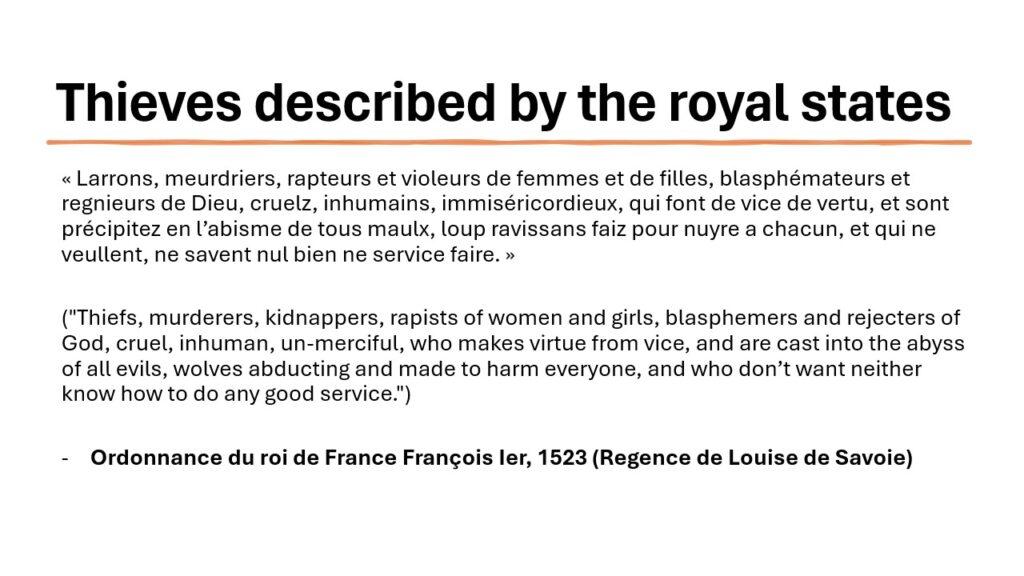

In fact, the word “brigand” appeared in the late medieval era and probably comes from the italian “brigandi”, professional fighters serving a Condottiere. During the Hundred Years’ War, “brigand” was first used to describe soldiers in their acts of pillaging, but also peasants that started to retaliate by regrouping in the woods. Afterwards, it’s been used to describe violent thefts.

So, to medieval minds, soldiers and bandits were close: the Witcher 3’s numerous bandit camps are for most part deserters or ex-soldiers preying on villages.

In France, and later in England, it began as a matter of sovereignty for royal states to distinguish soldiers from bandits. Ordinances associated thieves and brigands to vile behaviors but also cruel animals such as wolves, to the point they were dehumanized.

As “bandit” (from the occitan word “banned”) replaced multiple words used, we can understand why fantasy games make them such violent individuals . Many episodes of The Elder Scrolls series such as Skyrim don’t bother giving them names and fill its dungeons with bandits’ lairs: labeling them as bandits give players a clear sight over who should be talked and who should be attacked.

But in the meantime, the Thief is often included in playable classes of RPGs : 18th century’ literature began to heroize criminals against modern tyranny or corruption. From Robin Hood to Jesse James and the gangster in early Noir films, fantasy thieves inherit this subversive role.

Then, how does the thief differ from the bandit? Mainly because the thief doesn’t have to kill. In fact, games such as Dishonored use a morality system to give the player agency over their character: the good ending, labeling Corvo as a hero, is given when few people have been killed – where NPC’s, including bandits, won’t hesitate to act violent.

Bandits and Thieves are the two faces of the same coin of violence in RPGs. Like in fantasy literature, the difference between a protagonist and a bandit is the lesser degree of violence they use. Nonetheless, calling enemies bandits legitimize any use of violence by the player. Thanks for reading!

Further readings:

ŠVELCH Jaroslav, “Monsters by the numbers: Controlling monstrosity in video games” In M. Levina & D.-M. T. Bui (Eds.), Monster culture in the 21st century a reader, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013, pp. 193–208. TOUREILLE Valérie, Vol et brigandage au Moyen Âge. Presses Universitaires de France, « Le Noeud Gordien », 2006, URL : https://www.cairn.info/vol-et-brigandage-au-moyen-age–9782130539704.html

Thank you for the paper, Albert! It’s really interesting to see these appropriations in a historical perspective.

Your point about the absence of names, in particular, reminded me of Morrowind, in which every single bandit has a name. In fact, we often only realized if an NPC was a friend or foe if we approached them and were attacked.

This made for some counterintuitive exploration. E.g. “strongholds” were a type of settlement what was usually populated by enemies – but not always. Moreover, some important NPCs (like master-level trainers) could only be found in strongholds. This made sense lore-wise, as they were often outlaws or otherwise estranged individuals from society.

And, of course, the fact that every single enemy was framed as an individual person, with a name and family name, made killing anyone quite tense. This was before “essential” NPCs were a thing, so there was always the possibility we were ruining a questline (or the main quest itself) by shooting first and asking questions later.

That’s a very good point, I had Morrowind in mind when I was writing about Skyrim, where the bandits do actually have names. I didn’t know master trainers could be found in dungeon’s tho !

Morrowind is also interresting because even bandits could oppose a serious threat to an unprepared player – paralysis weapons in the hand of footpads is something you only remember in Morrowind. But as everybody remembers this game for its alien setting, having a way more “classic fantasy middle ages” grounded games as Oblivion reinforces the fact that bandits “aren’t meant” to have names. Morrowind is a notable exception.

Some of the master trainers in strongholds are people mentioned in the skill books (IIRC, the protagonist of the “Cake and the Diamond” is one of them). It’s pretty neat! But it’s something I totally missed when I first played the game, before walkthroughs and the internet!

I am now obliged to start a new playthrough to check it out !

Thanks very much for this Albert. Does this dehumanisation extend to the appearance of these bandits? Looking at the images above, there are a few commonalities such as dirty clothing, stereotypically brutish faces, and helmets which obscure faces. Is that deliberate?

Thank you for this question Dr Houghton ! As the appearance of the bandit do rarely coincide with “rules” or descriptions of the bandits in monster manuals or in game bits of lore, they often have the same features : cloaks, masks made with clothes, obscure faces : that contributes to their dehumanization as they are denied a face. The most stereotypical appearance for bandit can in fact be found in J-RPGs, as the sprites associated to the bandit-monster contains all of these feature (also, it should be mentionned that PC’s and important NPC’s often aren’t drawn or modelled with the same style as bandits : bandits are often drawn with the same artistic style as other monsters, dehumanizing them more).

But I do not think their appearance is the most dehumanizing feature they are given. Cloaks and masks are options for the player when he plays a Thief or a Rogue. The most important physical feature for the bandit is their rude behavior – that also means a rude face. They are dirty AND hateful, just like orcs in classic fantasy such as Tolkien. The bandits in RPG’s are no more humanized than the uruks you described in Shadow of Mordor !

Speaking of JRPGs in particular, do you think the overreliance on engines like RPG Maker (and, possibly, other ubiquitous asset packages) contribute to the stereotype?

I’m not sure this is something you looked into it yet, but it sounds like a fun research topic. If devs are not creating everything from scratch, where are they getting their assets from, and why?

The use of asset packages for DIY tools surely contributes to the stereotype – also, we could argue that the inclusion of bandits in default monster packages can be explained by the cultural influence of TTRPGs (wich are, to some extent, a tool for DIY adventures).

I doubt every tool can use the same bandit assets actually. As it is one of the first encoutners the devs can think of, it mostly has to match the artistic style chosed for the game.

On a side note, your question has reminded me of the illustrations for Chroniques Oubliées, one of the most used generic SRD’s for TTRPGs in France. As the book used original illustrations, the website of the SRD uses AI illustrations : https://www.co-drs.org/fr/bestiaire/famille-de-creatures/bandits

As you can see, it contains every feature mentionned by Robert Houghton, it’s very stereotypical. AI reinforces many stereotypes, and medieval-fantasy in not an exception !

Thank you Albert – those are some really useful connections!

Hi Albert, this report is really intriguing. I wanted to bring this news to your attention: in Southern Italy (where I live) the word “brigand” is also romanticized here and refers to the revolts following the unification of Italy. To make a long story short, in 1861 the kingdom of Northern Italy annexed the South, forming a single political reality, but many inhabitants of the South did not agree and began acts of brigandage aided by the peasants and people of the South. This revolt was suppressed with the killing of the brigands and fails, but even today there are various songs in Southern dialect dedicated to the brigands. I’ll leave you a link to one of these songs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubIGp0BTikw

Thank you so much Luigi, I didn’t know the word brigand gained another use in Italy in the 19th century ! I read a lot about the “romanticization” of the criminals starting the 18th century in western Europe (Schiller’s play “Die Raüber”, gang figures during the French Revolution) leading to the subversive use of criminal backrounds in litterature and nationalism.

Please note that the etymology for “brigand” is still discussed by French specialists, it’s quite unclear if the word “brigandi” was used for italian mercenaries employed by French captains, but one certitude is that it had a military meaning before being used for criminals and rebels !