By Blair Apgar (Kutztown University of Pennsylvania)

“I know Tassing seems big to you, but the world is so much bigger than we can imagine.” – Brother Sebhat, Pentiment

As past iterations of the Middle Ages in Modern Games Asynchronous Conference have demonstrated, representations of the Middle Ages in video games have traditionally been steeped in Euro-coded (albeit it highly genericized) visual language, implicitly reinforcing the notion that the Middle Ages belongs only to white Europeans. Pentiment (Obsidian Entertainment, 2022) offers a rare and instructive departure from this trend through its portrayal of Sebhat of Sadai, an Ethiopian monk whose character is grounded in the distinct traditions of Ethiopian manuscript illumination, grounding his presence in a coherent and legitimate historical world. Sebhat’s design exemplifies how regional visual language can be effectively used, if briefly, to decentralize Eurocentric notions of the medieval past in games.

Sebhat is introduced in Pentiment’s first act, staying at Kiersau Abbey as an envoy from the Ethiopian Church in Rome, perhaps based on three Ethiopian monks, P̣etṛos, Bärtälomewos & Ǝntọnǝs, who Verena Krebs has traced across various fifteenth-century sources and who were documented in attendance at the Council of Constance—the same council of which Sebhat makes mention to Andreas.1 While his appearance nominally conforms to the game’s decorative use of simulated pigment on paper, Sebhat’s character design is marked different from that of Andreas and the other monks at Kiersau (Figure 1). Andreas, like most characters in the game, is drawn in a style reminiscent of late medieval Central European visual culture, particularly influenced by woodcuts, marginalia, and the illustrative conventions of early printed books. His features, distinctly influenced by the numerous illustrations of the fifteenth-century Nuremberg Chronicle, are defined by sharp contours, minimal shading, and a linear emphasis on outline over volume.2

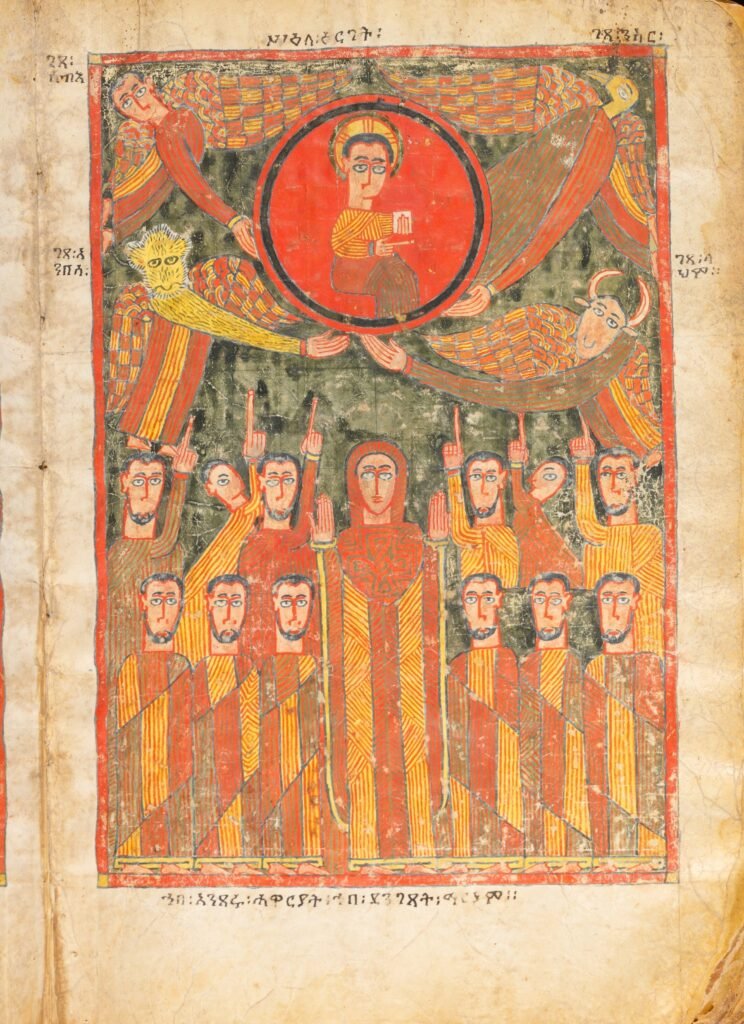

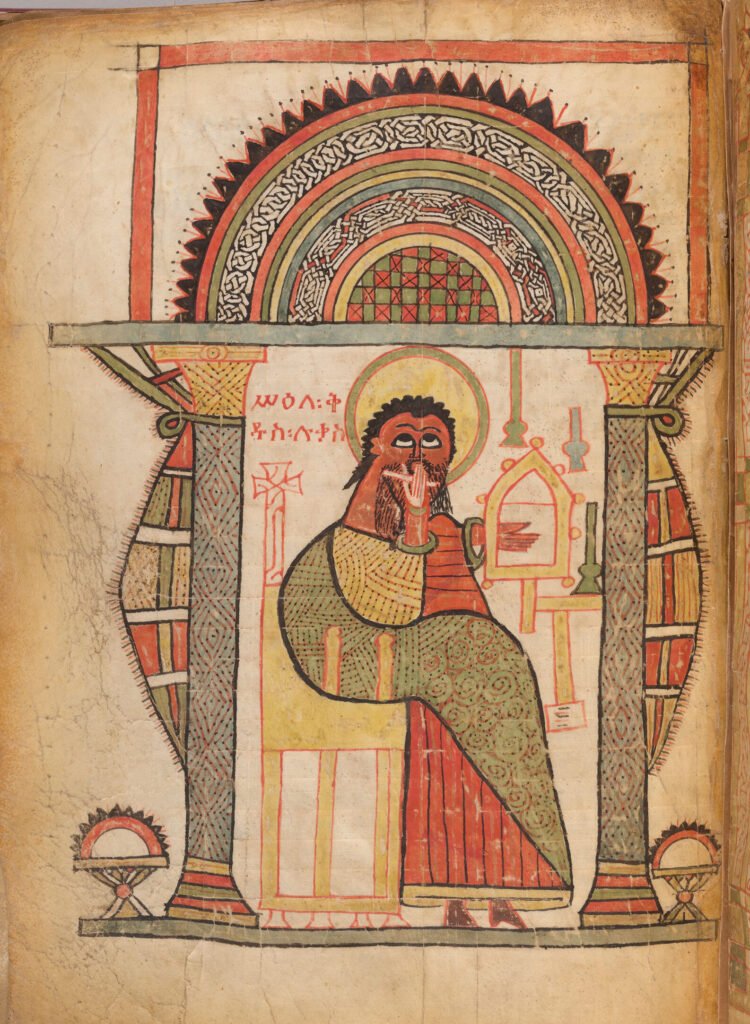

In contrast, Sebhat’s character design draws from the Ethiopian Christian manuscript tradition. His elongated, almond-shaped eyes, narrow nose, darker skin, and stylized curls reflect visual conventions found in medieval Ethiopian manuscripts. That Sebhat’s face is lined in red (Figure 2), rather than black as his European counterparts, reflects a tradition found in Early Solomonic Period manuscipts (Figure 3).

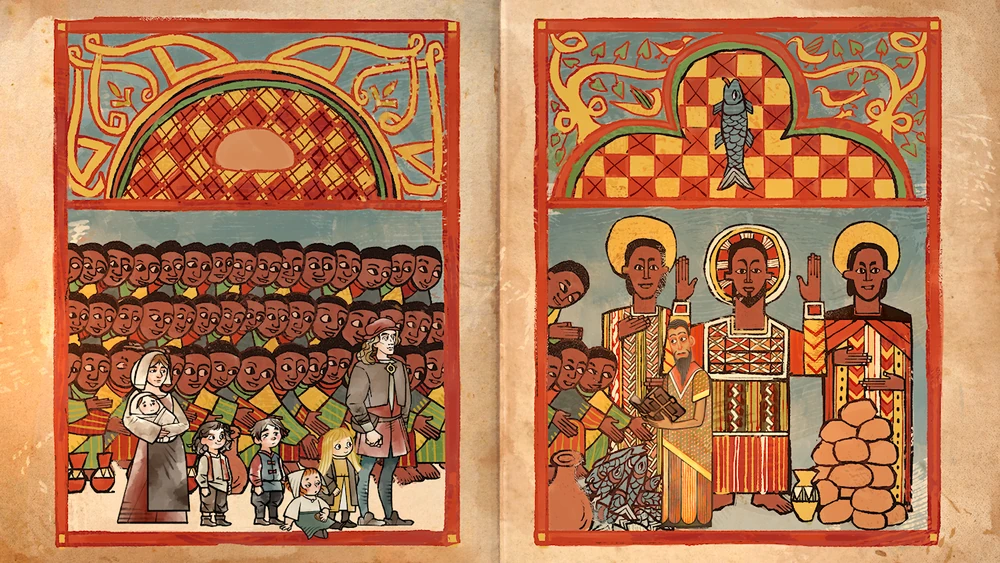

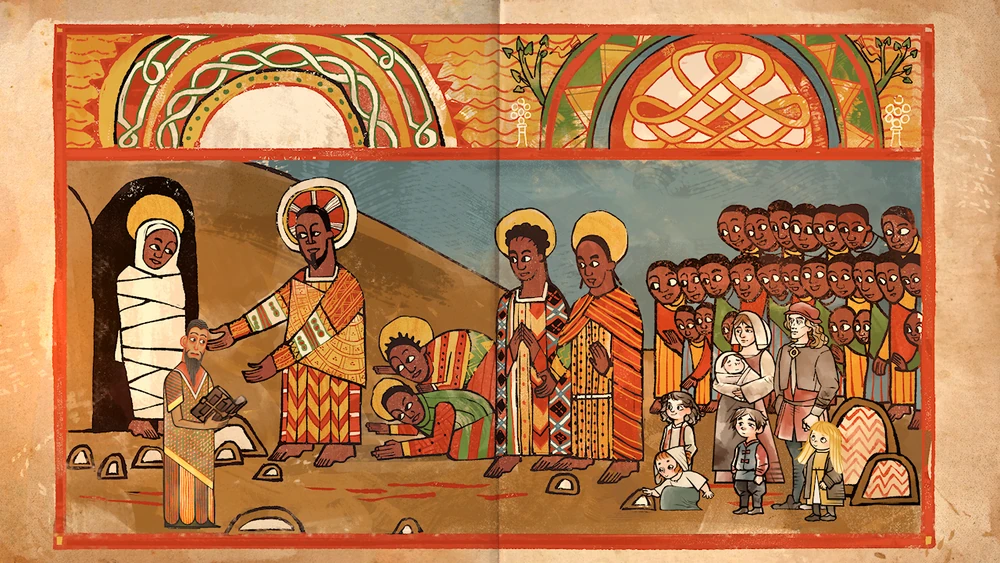

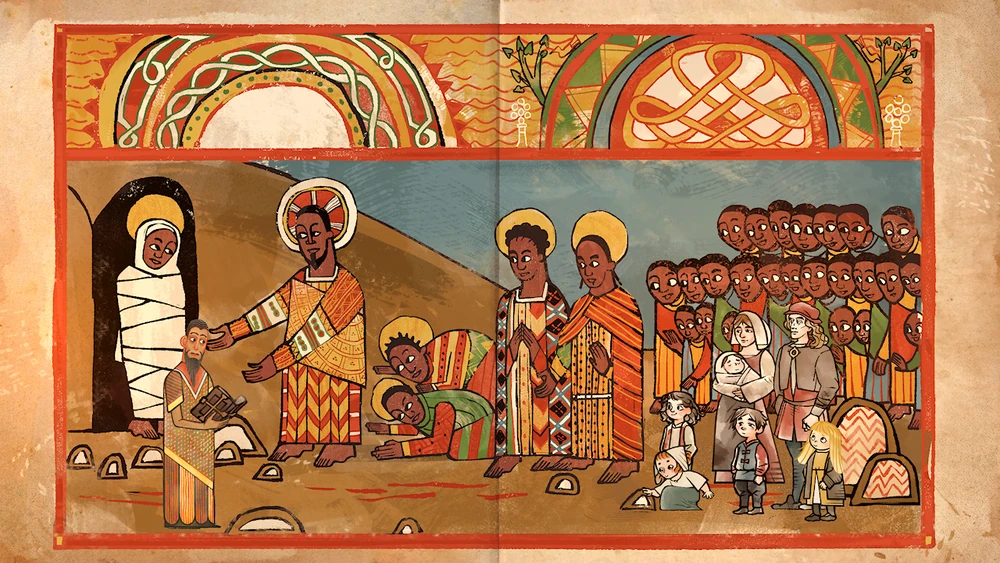

His clothing is marked by rhythmic folds and bold color contrasts, evoking the palette and visual construction of figures found in contemporaneous Ethiopian texts such as the Zir Ganela Gospels (New York, The Morgan Library and Museum, MS. M.828, Figure 4).3 Additionally, Sebhat’s robes are rendered with layered textural patterns—repetitive bands, crosses, and woven-like motifs—that recall the traditional textiles of his homeland.4 These same patterns later appear in Sebhat’s recollection of the Raising of Lazarus and The Feeding of the Five Thousand on the garments of Christ and his apostles (Figures 5, 6).

Thus, these patterns are not simply decorative but signal a different cultural system of visual storytelling, one in which materiality and surface intricacy are charged with intermingled historical, theological and liturgical meanings. Though his appearance within the game is restricted to the first act, the player is offered a chance to more deeply engage with Sebhat during a shared meal. In the background appears a portrait of Saint Maurice who, by the fifteenth century, was predominantly depicted with African features (Figures 7, 8), subtly anchoring the game within a network of African-European contact.5

After the meal the player is transported into Sebhat’s illustrated stories. Like his character portrait, the scene adopts the aesthetics of medieval Ethiopian illuminations: vivid yellows, reds, and greens with thick graphic lines. The top of the page features harag, a Ge’ez term referring to the bands of interlacing tendrils used to frame scenes.6 Biblical characters such as Christ and Lazarus are depicted with African features and darker skin.When asked about this difference, Sebhat’s answer notions to the world beyond Tassing, recentering the story through his cultural lens.

This scene casts Andreas and Tassing as outsiders, repositioned within a new visual language. Though brief, this inversion destabilizes the default Eurocentric aesthetic and places Sebhat’s perspective on equal visual footing, generating a moment of aesthetic parity. Crucially, this does not exoticize Sebhat, but affirms the presence and legitimacy of the Ethiopian Middle Ages. In effect, the game stages a dialogue between manuscript cultures—Central European and Ethiopian—without collapsing one into the other, allowing each to retain its visual and epistemological specificity. Sebhat’s inclusion in Pentiment represents a meaningful intervention in the typically Eurocentric visual culture of medievalist games—one that re-centers a non-European manuscript tradition within the game’s visual and narrative logic, positioning it as a part of the extended medieval world, rather than as an exotic aside. When a game depicts an outsider through the aesthetic style of their own tradition, it not only expands medievalist game aesthetics beyond the European Middle Ages, but also models a compelling strategy for reimagining how the medieval world can be visualized in games.

Notes

- Krebs, Verena. Medieval Ethiopian kingship, craft, and diplomacy with Latin Europe. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021, 34-37. Krebs, Verena (@KrebsVerena/@Tweetistorian). “How 3 Ethiopian monks crossed the Alps…” Twitter, April 20, 2021, 15:37. https://x.com/Tweetistorian/status/1384597109664534528 ↩︎

- Bedingfield, Will. “Pentiment’s Director Wants You to Know How His Characters Ate.” WIRED, November 17, 2022. https://www.wired.com/story/pentiment-josh-sawyer-interview/. ↩︎

- Zir Ganela Gospels, 1400-1401, 207 leaves (2 columns, 25-29 lines), vellum, 362 x 251 mm, MS. M.828, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. https://www.themorgan.org/collection/zir-ganela-gospels ↩︎

- Gervers, Michael. “Cotton and Cotton Weaving in Meroitic Nubia and Medieval Ethiopia.” Textile History 21, no. 1 (January 1990): 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1179/004049690793711244. ↩︎

- Jung, Jacqueline E. “Reflections on Africans in Gothic Sculpture, Part 1.” Yale University Press, April 12, 2022. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/2020/07/21/reflections-on-africans-in-gothic-sculpture-part-1/. ↩︎

- Zanotti-Eman, Carla “Linear Decoration in Ethiopian Manuscripts,” in African Zion: The Sacred Art of Ethiopia, ed. Marilyn Heldman (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 63–67. ↩︎

Thank you for this paper, Blair. Sebhat and the meal you share with him were nice surprises when I first played Pentiment, since, as you accurately point out, it allows for an approach to the medieval world that does not need to be subordinated to an exclusive European prism. This is not unlike the case of Musa of Mali that Simone mentioned in our previous paper, and I was wondering if you know of other examples in medieval games that could be analogous?

I also liked the case of Sebhat because it allows the player to approach forms of medieval Christianity that are not Western or European, emphasizing its own diversity during the period. What other ways do you think could be used to emphasize this diversity beyond what Pentiment does?

Thanks for your comment Juan! I’d have to think a bit more if there are other games like this–I can say that the use of distinct visual styles is not something I’ve come across, if simply because photorealism reigns dominant in character/world design for medieval games (though this appears to be shifting somewhat).

One of the most important steps studios could take is to move away from treating European cultural objects, dress, and architecture as the unmarked default. Instead, when games incorporate regional-specific character and environmental design with equal attention and depth—allowing each to stand as a complete aesthetic and cultural system—they begin to feel like fully realized alternatives rather than simply “European but with different colors.”

A decent example might be the Royal Court DLC for Crusader Kings III, which, while not perfect, does make some effort to inflect courts with cultural specificity—like including horseshoe arches in the Seljuk court or marble Corinthian columns in the Byzantine one. These kinds of visual cues can help shift the perception of non-European settings from marginal curiosities to integral parts of the broader medieval world.

Complimenti Blair, articolo interessantissimo!

Ho amato Pentiment e l’attenzione dei suoi sviluppatori nella rappresentazione di tutte le culture che incontriamo in gioco è sbalorditiva. Sebhat è uno degli esempi che si possono citare. Mi chiedevo se ci sono state delle critiche su questo personaggio. A memoria non ricordo nessun problema a riguardo e, anche su Steam (https://steamcommunity.com/app/1205520/discussions/0/4330852522340940077/), l’unica discussione “critica” è quantomeno costruita e non un semplice sfogo senza pensiero come fu per Musa di Mali di KCD II.

Ancora complimenti.

Grazie mille! Non ho visto molte critiche da parte dei giocatori, e ne sono davvero grata. Ci sono stati alcuni commenti che suggeriscono che Sebhat sia un personaggio “token”, ma per fortuna il dibattito è stato, nel complesso, abbastanza sereno. Mi chiedo però se il fatto che la sua storia sia opzionale abbia fatto sì che molti non l’abbiano nemmeno incontrato; forse, se fosse stata parte integrante della trama principale, le reazioni sarebbero state più aspre.

Just wanted to say that I enjoyed reading your paper, Blair, and thx for bringing attention to this game – I now have it lined up for my gaming this weekend, I’ll be paying attention to the points you bring up as I play!

I’m glad! It’s a great game, so I hope you enjoy it!

Thank you for this paper Blair, very interesting read. This is probably a minor question, but do you think there is potential for games like Pentiment to be considered in eventuality historical sources or art histories, that is serving as preservations of existing or known and/or disseminations of new productions or variations of Medieval artworks across different cultures and regions (as has been thoroughly covered here)?

Thank you for this paper Blair, this was an interesting read. This is probably a minor question, but do you think there is potential for games like Pentiment to be considered in eventuality historical sources or art histories, that is serving as preservations of existing or known and/or disseminations of new productions or variations of Medieval artworks across different cultures and regions (as has been thoroughly covered here)?