By Robert Rouse (University of British Columbia)

Introduction

The latest iteration of the longrunning AAA franchise Age of Empires was developed in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada during the period 2017-21. Development was undertaken by Relic Entertainment, a Vancouver developer, in conjunction with World’s Edge, the Microsoft owned studio and IP holder. From 2017-21, I acted as a SME (subject matter expert) consulting with Relic on historical, cultural, and linguistic aspects of this popular recreation of the medieval world (in particular the English civilization). This short paper addresses some of the design features of the game that contributed to its ‘progressive’ view of the medieval, a conceptual decision that was not uncontroversial amongst parts of its fan base. This ‘progressive’ Middle Ages can be seen to reflect the cultural values of the locus of its regional development (British Columbia and the US Pacific North-west), and the corporate policies (as they were in this period) of the IP holders, Microsoft. The significance and impact of this iteration of the Middle Ages is grounded in the both the franchise’s reputation for historical accuracy, and in its large player base (over a million copies were sold on launch, and over 5 million since 2021, without taking into account X-box live subscription play).

The Progressive Design

Spurred partly by advice regarding recent scholarly work on racial and gender diversity in medieval Europe, and partly by a desire to represent the game’s diverse potential audience, design decisions were made to have recruited units represent a diversity of skin colour and gender in the game. To this end, variation in the appearance of spawned units was built into the game design. For the purposes of this paper, I will examine the appearance of, and controversy surrounding, the presence of female troops in the Mongol civilization.

Here (figure 1) we see the alternate unit design for the female (left) and male (right) Mongol troop units. These alternate designs were replicated across many unit types across the various civilizations.

The Inevitable Reaction

As anticipated in the consultation process, this design decision produced a predictable response from certain corners of the online community.

In figure 2, we see the pejorative of ‘SJW’ (social justice warrior) being applied to the design decision when witnessed in a pre-release trailer. The decision to highlight diversity is immediately associated with the prevailing culture war politics of the early 2020s, raising the inevitable spectre of #gamergate.

Image 3

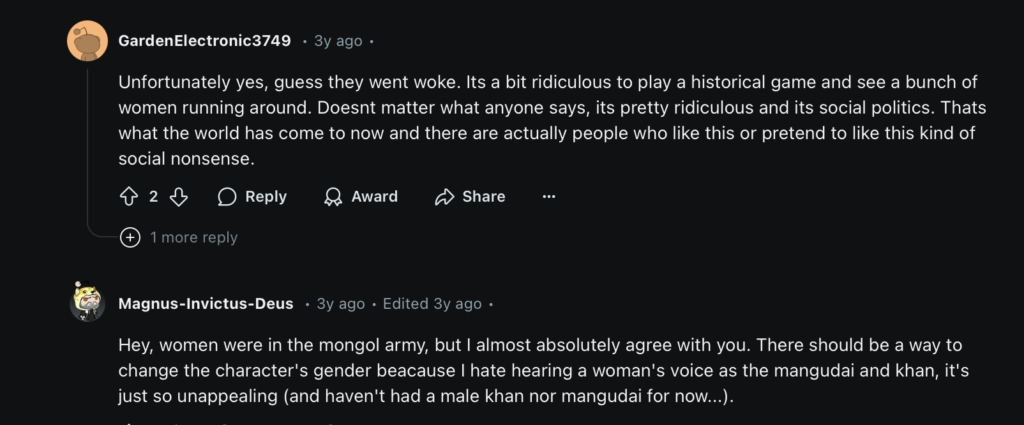

In figure 3, the observation focusses on the Mongol civilisation, the most gender diverse troops in both the game design and historically.

Figure 4 continues this outraged debate, identifying the decision as a doubly ‘ridiculous’ choice and reading it as ‘social politics’ and ‘social nonsense’. The next comment counters this by pointing out the women were in fact present in historical Mongol armies, but then changes direction to cast a personal critique that they ‘hate to hear a women’s voice’ in this medieval video game, as it is ‘so unappealing’.

The So What?

The past is always mediated through the discourse of the present. The medieval as a space of radical potential, a place where progressive values can be identified and progressive genealogies highlighted, is important to a view of history that aligns with current progressive values. We all recognise that many progressive values have deep genealogies – often disrupted by modernity, the englightenment, and a host of other historical moments and movements – that track back into the premodern, and excavating these in our reconstructions of the medieval highlights their value to our understanding of the past, present, and future.

This progressive vision of the medieval is constantly under assault by other more conservative visions of the past; alt-right, white nationalist, and other nostalgic visions compete to define the popular experience of the medieval. In Age of Empires IV, produced in the late 20-teens, we see one particular imagination of the medieval past that was rich with a diversity – linguistic, cultural, gendered, and ideological – that spoke to a progressive view of our own time and place.

As a final coda, one might wonder what would Age of Empires IV might look like if made in 2025, in the USA, now that Microsoft (and so many other US corporations) have rolled back DEI initiatives and other progressive aspects of their corporate culture; perhaps it would be the Dark Ages instead.

Suggested Readings

Age of Empires IV Behind the Scenes Dev Diary, “Music and Voice-Over”, October 2021:

Age of Empires IV, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9063072/

Thanks for a very interesting paper, Robert. It reminds me of the female general controversy in Total War: Rome 2 back in 2018 (which I just wrote into a historical games module I’m teaching). Apologies if you already mentioned this and I missed it, but not having played AoE4 yet, I was just curious if female soldiers can spawn in other cultures aside from the Mongol one? And also, is there similar conservative backlash to the skin colour variation you mention, or has that reaction been most vitriolic against these female Mongols?

Yes, the gender variation mechanic is built into all the civs, as far as I am aware, to a lesser or greater extent. On the question of skin tone (which is gradated, not binary), there was indeed a similar (but much less pronounced) range of criticisms. The recent work done (and a being done) by scholars such as Dorothy Kim (and many others) is reminding us of the (often erased) racial diversity of medieval Europe, and this was part of the work that the developers were alerted to.

For some reasons (about which we can speculate), the gender representation provoked more vocal opposition online.

Thanks for this. That is very interesting that the criticism was so (relatively) selective, but I suppose it reflects what happens when “the internet” seizes on a specific example.

Thanks for this – this is a really interesting paper to compare to Shu Wan’s discussion of the logics of RTS as inherently extractive/imperial in nature earlier today, thinking about the ways that even a relatively minor bit of visual progressivism gets jumped on (and indeed potentially gets jumped on more than a mechanical overhaul might be).

I guess the age-old question here is: is there anything much one can do about any of this? Understanding that the present mediates the past is one thing, but how in your view can historians and developers use that insight to better engage with some of these problems?

Great question: what can we (or game developers) do about this? In my mind all they can do is construct the medievals that (a) accord best with current research, and (b) make for an attractive engaging game world. Medieval games play a not insignificant role in attracting the next generation academics and students to the study of the medieval world, and the media representations that draw them in select for certain people, for certain ideologies. If we make these worlds more welcoming a diversity of players, then we get a greater diversity of scholars 20 years later.

Thank you very much for this paper, Robert! It is always interesting to get a little peek into the concerns that developers have when approaching the past and how the audience reacts, especially when much of our popular ideas about the Middle Ages are mediated by contemporary politics. I was wondering if you could expand on your experience working with Relic? How did the concern with accuracy vs. the expectations of the fan base impact these design decisions?

Furthermore, it is very interesting how some in the fan base, who claim to be concerned with accuracy, also dismiss it right away when it does not accommodate their (political?) understanding of the past. What could we do to better address these issues from a game development perspective?

My impression is that accuracy vs game play is always a dynamic debate; accuracy will of course be sacrificed (often due to simplification) to improve the game experience, but some developers seem to be more committed to have at least a sense of “historical plausibility” (if not always accuracy) than other; Relic always seemed very interested in being as accurate as they could be, without sacrificing gameplay.

Thanks so much for this really interesting paper, Robert. Have the AOE devs found that the reception generally has shifted over time? And, I guess thinking about mods as I did last year, has the game been the subject of the ‘anti-woke’ mods which might change the female warriors?

Hi Blair,

I can’t really speak to the impact of more recent mods, as I haven’t been involved since build-up to the X-box launch in 2023, but given the degree of “outrage”, and the continuing “anti-woke” discourse (especially in the US), I would b surprised if this was not the case.

Great paper!

Age of Empires IV features numerous mini-documentaries and historical insights unlocked through achievements. I’m wondering whether any of these explore the presence of women in the Mongol army?

These kinds of insights can be a good way to contrast this type of reaction from certain segments of the audience?

Not that I know of (the mongol mini-docs); the “hands on history’ mini-documentaries (that are very [popular with the player base) tend towards material culture (the Mongol Horse, Making the Mongol Bow, etc). We do see some highlighting of historical women as leaders in the game, which is refreshing (many have been largely ignored in more traditional views of the medieval past), including the highlighting of Matilda of Flanders (wife of William the conqueror) in the tutorial material for the X-bow launch of the game.

This is such a good, clear example of a dynamic I’ve observed between game mechanics on the one hand (in which complexity is an end in itself, because it makes the system more interesting) and “historical accuracy” on the other (in which a question like DEI is pertinent, because are we really representing historical Mongols or are we imposing our values on Mongols?). In theory, these aesthetic principles want the same thing when games promise to be simulations whose complexity models the actual complexity of real-life systems. But in practice these are two separate things: medieval warfare was probably not very fun, and so a fun game about medieval warfare has probably diverged in some intentional way from being an accurate historical model. I feel like part of what is so incoherent about debates like the one you’ve documented is that people switch back and forth between these two separate arguments in a bad-faith way: you can think women Mongols are historically inaccurate and you can hate hearing women’s voices in games, but those are actually two separate and unrelated judgements. Anyway my question from all of this is how you think game developers might address this conflation and expose it? What did Relic get right here, what lessons could we learn from how it went?

And just to clarify / distinguish my question from the discussions above, part of the challenge I see comes from the “historically accurate” branding you’ve described, which lends itself to the conflation. They want to be as accurate as possible without sacrificing gameplay, is there a way of making their principles and methodologies more transparent to players without losing them in the effort?

Hi Stephen,

Part of what Relic did well in this regard was in the generous use of developers blogs (during development) and inside view videos (building up to the 2021 release), and through the active management/engagement with fan communities (since it was an established franchise) via Community manager staff. I’d have to go back through this extensive archive to check, but information about and conversations explaining design choices were fairly transparent in the lead up to and after the initial release. I think this was a very different process than in a non-franchise game that doesn’t have an existing community to engage with prior to release.