By Vinicius Marino Carvalho (Universidade Estadual de Campinas)

Is this the way out?

Modern fantasy shares a relatively consistent set of narrative and aesthetic references, roughly informed by medievalist artistic traditions dating back, in some cases, to the age of Romanticism. These tropes are “tightly linked to Northern and Western Europe” (Houghton, 2024, p. 224), yet are often drawn upon as an intellectual ‘commons’ which “belongs to everyone – and so do not belong to anyone in particular” (Harrington, 2025).

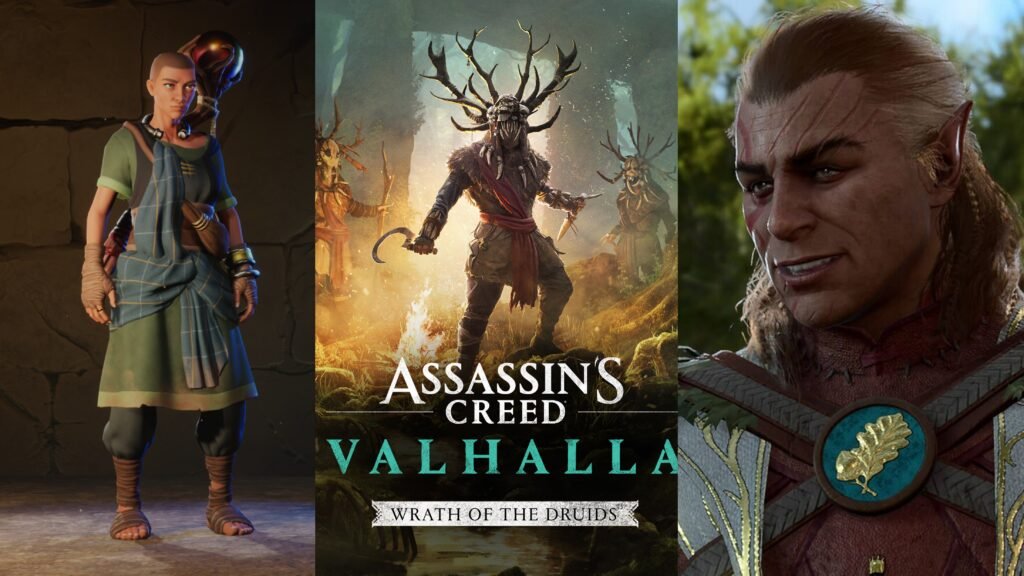

The Commons has its uses. Most game developers thread lightly around borrowing elements from non-Western, non-Hegemonic cultures. After all, even established academics have (been accused of) cultural appropriation. ‘European’ fantasy, on the contrary, is safe. King Arthur, Vikings, fairies, and druids, are, for all intents and purposes, stock characters at everyone’s disposal.

The problem is that the ‘West’ is not as stable an entity as some of its inhabitants believe. Its borders shift in times of geopolitical uncertainties. Places like South America are othered by Europe and North America, yet struggle to come to terms with our own Europeanized cultural heritage. Medievalist reception reacts accordingly (e.g. de Souza, 2024): we’re denied belonging within the Commons, yet, like Eco (1987), still dream about the Middle Ages. Possibly, and worryingly, because this dream “is the only one still alive” in our colonized imagination (cf. Chakrabarty, 2000, p.5).

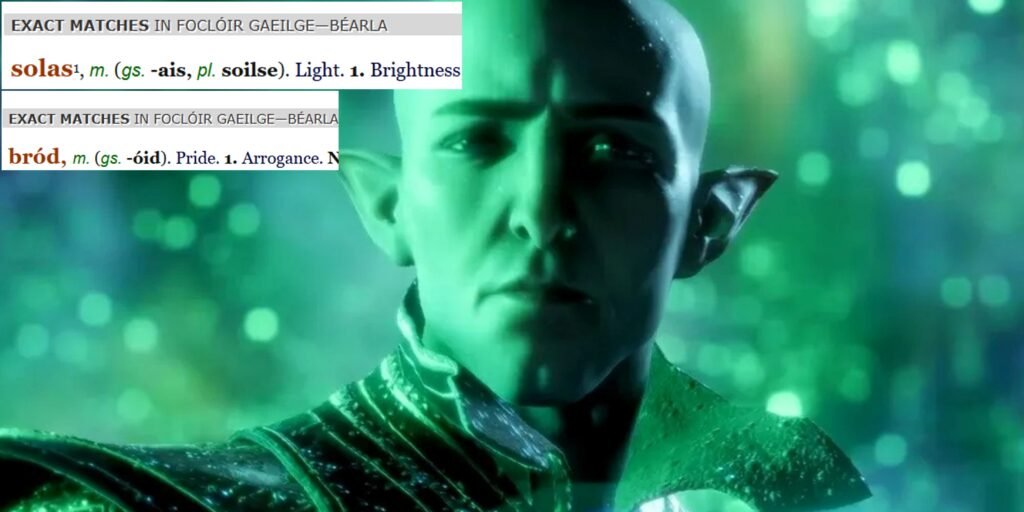

At the same time, the fiction of the stable West ignores centuries of internal colonialism within the Europe itself. This can be observed, for example, in the case of the Celtic-speaking peoples. Celtic languages are often used in games (and in Western fantasy as a whole) as a proxy for gibberish. Celtic peoples and countries are associated with backwardness, magic and an exotic love for nature – often, in a racialized manner, as the connection of Celticness with elves highlight (Ní Dhúill, 2019).

No, Solas doesn’t mean “pride” in Elvish

Why does this matter? First, because these appropriated traditions, and the processes through which they have been appropriated, are as much part of fantasy’s legacy as druids and fairies. Second, because focusing on regionalities can be a way of safeguarding elements now part of the ‘Western’ commons in an age when the ‘West’ is threatening to crumble as a cohesive concept. Contemporary fantasy literature has been attempting to explore different worlds and stories that push back against colonialist, agonistic fantasies of yore (Oziewicz et alli, 2022). Games can do the same – and minority and/or forgotten traditions from the Middle Ages can serve as inspirations.

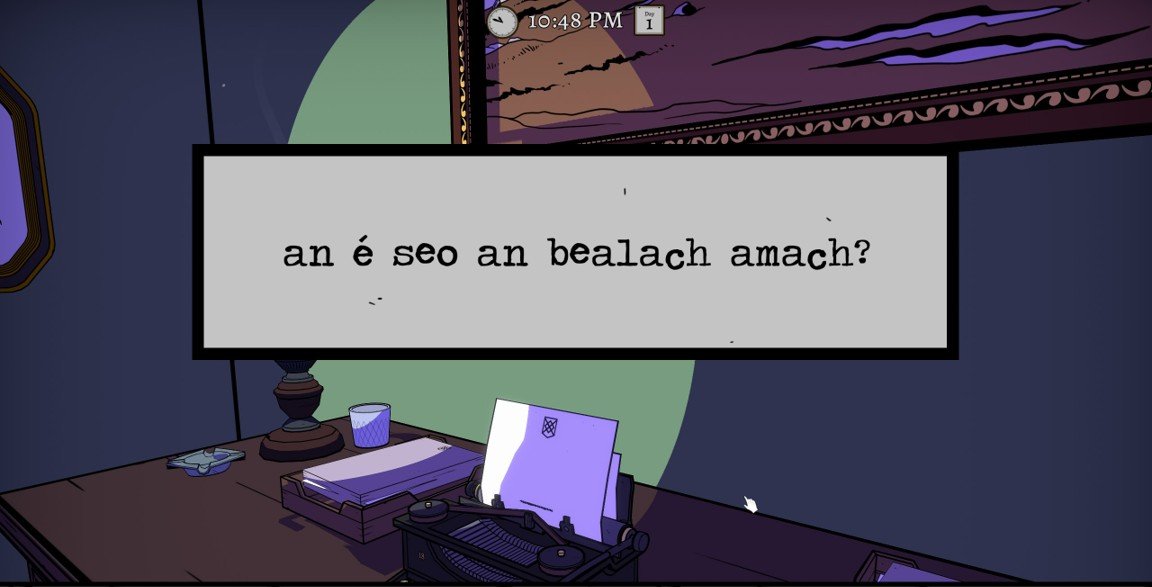

Utopianly, drawing on these ancient [1] sources would allow games to explore new story structures and reward mechanics better suited to a post-Western world within which the hegemonizing clarity of the ‘commons’ will no longer be appealing. Pragmatically, even if games fall short of such a cultural impact, the mere existence (and, hopefully, future ubiquity) of games like Tales of the Mabinogion, from our first keynote speaker Stevan Anastasoff, is a reminder that there is a way out: authenticity – not in terms of history, but in being true to oneself – is a choice we still get to make, even in a cultural landscape that tries to steamroll us into homogeneity.

Notes

[1] I am using ‘ancient’ in lieu of pre-modern or non-modern to avoid interpreting this past in the terms of what came after. I do not mean exclusively Antiquity though; my comments also apply (and are primarily aimed at) the medieval period.

Bibliography

CHAKRABARTY, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton University Press, 2000.

DE SOUZA, Rebecca. Are There Limits to Globalising the Medieval? postmedieval, v. 15, 2024, pp. 257-83

ECO, Humberto. Dreaming of the Middle Ages. In: Travels in Hyperreality. Harcourt, 1987 (First edition: 1973)

HARRINGTON, Nat. The Celts Meet Celtic Fantasy. Strange Horizons, Jan 27th 2025 Issue. Available at: http://strangehorizons.com/wordpress/non-fiction/the-celts-meet-celtic-fantasy/

HOUGHTON, Robert. The Middle Ages in Computer Games. D.S. Brewer, 2024

NÍ DHÚILL, Orla. Do American Writers Think Irish is Discount Elvish? August 24th, 2019. Available at: https://orlanidhuill.com/2019/08/24/do-american-writers-think-irish-is-public-domain-elvish/

OZIEWICZ, Marek et alli. Fantasy and Myth in the Anthropocene. Bloomsbury, 2022

Thank you for your interesting reflection, Vinicius. As a fellow Latin American, I often find it odd how the notion of “Western” is constructed as it tends to exclude Latin American societies despite sharing many of its characteristics (like Christianity, secularism, and colonialism).

As you point out, deconstructing this category is useful to see the many nuances and diversity of it. I am intrigued by your approach to authenticity, not on “history, but in being true to oneself”. How would this be implemented in simulations of the Middle Ages, in particular, and history in general?And also, do you think that the use of counterfactuals can be useful from this approach to offer more nuanced approaches to history in gaming?

Well, this is very trick for us, because the medieval heritage is an imported one – and also particularly tied to a settler population many Latin Americans don’t identify with. I teach a mostly non-white class, with a handful of Indigenous students every year, and is very often a struggle to make them care about the Middle Ages at a personal level.

So I don’t think we’ll ever feel authentic in producing/consuming medievalist media in the same way Stevan is doing with “Tales from the Mabinogion”, for example: crafting a story that is *personally* important, and deals with his relationship with heritage on very personal level.

Maybe, instead of being authentic, what we could try is to approach these borrowed tropes from a position of wonder or enchantment, celebrating uncanniness rather than trying to look for familiarity. Shawn Graham and Florence Smith Nicholls have recently defended that opinion in relation to archaeogaming (Florence’s paper is available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.05411)

I think counterfactuals can indeed help, as long as they point us toward speculation (in Cameron Kunzelman’s definition, as the attempt to portray the world as it isn’t) and not toward the reinforcement of particular tropes (as Ylva Gruftstedt problematized of Paradox’s games).

As an addendum to the paper:

Unfortunately, I didn’t watch Ryan Coogler’s “Sinners” until after I submitted this paper (otherwise, I’d have cited it!). But, for those of you who might have watched it, its use of vampirism as a metaphor for cultural appropriation covers similar ground to what I’m calling here the ‘commons’.

“Sinners” goes one step further and discusses what happens when this appropriation is racialized – and what does a ‘commons’ even means when the attribute of commonality is tied to whiteness. But, as the movie itself recognizes, this particular modus operandi of cultural theft also applies to pre-modern Europe (and Ireland, specifically). In fact, the first scene in the movie alludes to the filí (Irish poets of the medieval/Early Modern writing tradition), and the main villain is an Irish man who was ‘vampirized’ by the English centuries ago.

Thanks VInicius, a lot that’s very thought provoking there!

I was thinking more about your question on music last night, and reading what you’ve written here is pushing the questions further… What does it even mean to talk about something like “Welsh culture” anymore? Taking the example from your question yesterday, when even Welsh people associate traditional music with harp and voice, and barely anyone even plays Crwdd or Tabwrdd anymore, in what sense is that older style still a part of Welsh culture at all? If the Crwdd is not a part of _anyone’s_ lived experience any more, is still really part of anyone’s culture??

I’ve also encountered the same thing in other areas, for example with the environments, were I’ve had comments from Welsh people that the forests “don’t feel very Welsh”, ignoring the fact that the majority of forests in Wales today were planted in the last couple of hundred years, the older ecosystems having been almost completely destroyed.

Bringing this all back to your paper… I can’t help feeling a tension between what you say about regional traditions being a way of safeguarding what’s been absorbed in to the ‘Commons’, and this question of, well what if those older traditions have themselves already been forgotten within the region itself, already pushed aside by more dominant narratives? WHo’s culture are we really preserving? Is it preservation or revival? Or even re-invention…??

Very good questions, Stevan! I’ll try to address them the best I can, but keep in mind these are things historians and heritage experts have been grappling with a lot in recent years, and there’s no silver bullet.

The ‘easy’ answer is that Welsh culture is whatever the Welsh people want it to be. That can include living traditions as well as invented ones (like how kilts, a super recent piece of apparel, were taken as a timeless symbol of Scottishness). Sometimes, we even incorporate foreign elements or even things that had never been real (Allison Landsberg used the term ‘prosthetic memory’ to refer to the imagined pasts we absorb from mass media, for example).

The game 1000xresist offers a beautiful demonstration of this. I won’t spoil it in case someone reading this hasn’t played it yet. But let’s just say there’s a very touching scene in the game about a memory of Hong Kong prior to the Umbrella Revolution – one place in one moment in time none of the characters have seen, and which doesn’t exist anymore, but which they carry forward as an inherited memory.

The game returns to the implications of this scene by the end, in which the player has to literally choose what they wish to carry with them to the future. With the caveat that we can never take everything. We always choose somethings and let other things be forgotten.

The ‘hard’ answer is that all of this depends on who exactly, the Welsh people are. An author called Benedict Anderson once wrote that human societies are imagined communities. All it takes for a group to form is for its members to believe they share some commonality.

But in practice, unfortunately, people seldom agree with one another. Some people cling to exclusionary definitions of identity, like saying Black people can’t be Irish/Welsh/etc, even if they know more about the countries’ traditions and language than a lot of their white peers. Some people prioritise some cultural elements in lieu of others – like the many Irish individuals who don’t care for the Irish language, or for the historical connection between Irish nationalism and Catholicism. Some are part of regional communities that have their own thing and don’t feel represented by identity discourses at the national level. (This is super common here in Brazil, which not only is a continental country, but also a somewhat decentralised federation. Like in the US, some people relate to their states more than the to the union. Income inequality and structural racism also contributes to limit identity-building across class lines).

So, to end my digression and return to your question, I guess it’s ultimately a matter of how to address these conflicts – all the while acknowledging they will never be entirely solved. As long as there are different people around, with different ideas of what is this community they would like to imagine should be, you’ll have competing views of what does it mean to be Welsh (or Irish or Brazilian or whatever).

Many thanks for the detailed response, Vinicius – much food for though!

Thank you for this brilliant paper, Vinicius!

You raise excellent points about the reception of medievalism. I completely agree with your argument that Western tropes are often seen as “safe” in terms of cultural appropriation. I was also wondering whether the avoidance of regionalities and more innovative forms of medievalism—particularly by mainstream developers—could be attributed to racial bias among target audiences.

Thank you, Emilienne! I’m glad you liked it.

There might be a racial bias, but I it’s not very straightforward, and I think goes well beyond target audiences.

There is a racial component to Modern Western identity, and people who live within and are privileged by this hegemonic status tend to be oblivious to it. We like to think the Enlightenment was a a turning point for human rights, but the definition of “humanness” within the Liberal tradition was always very narrow. You have to be a very specific kind of man (often, in a deliberately gendered sense), with a specific form of agency, to be considered a full-fledged human worthy of having your rights respected.

Acknowledging regionality (i.e. admitting, to paraphrase Bruno Latour, that “We have never been Western”) would require problematizing both this paradigm and our tendency to impose it on other societies. And this is not something a lot of developers and players want to do. You can see a good example of it in Johansen Quijano’s analysis of Black Desert Online in this conference. People might look differently, but there is an unexamined universality that is taken for granted. Consequently, agency disparities and different ways of being in and interpreting the world are left out.

Mind you, this is something that afflicts medieval studies as much as commercial gaming. The very idea of applying the Middle Ages framework to other societies with their own temporalities carries the assumption that Western categories are universals – and consequently, that the “Western Man” and “Western Society” are ideal types that can be used to typify anyone, anywhere.