By Emilienne Parchliniak (Sorbonne Nouvelle University)

If Western games usually consist of an amalgamation of Christian stereotypical material perceived as medieval, many non-European games have appropriated the Middle Ages, drawing inspiration from other religious sources to shape a new kind of medievalism. A perfect example of this is found in Teyvat, the multicultural world of Genshin Impact.

In this Chinese-owned game released in 2020 by Hoyoverse, players begin the game in what seems to be an archetypal version of medievalism. They start their journey in a region with green plains and mountains reminiscing of European landscapes, before entering the clearly German-inspired capital city of Mondstadt, towered by a Gothic church dedicated to the God of Freedom.

Figure 2: Genshin’s first region: Mondstadt

Figure 3: Favonius Cathedral of Mondstadt

Most playable characters are either clergymen or knights: the former are usually healing units and the latter are damage-dealing, while most non-playable characters are civilians. Mondstadt’s society therefore parallels the tripartite social order in medieval Christendom, with oratores (those who pray), bellatores (those who fight) and laboratores (those who labor).

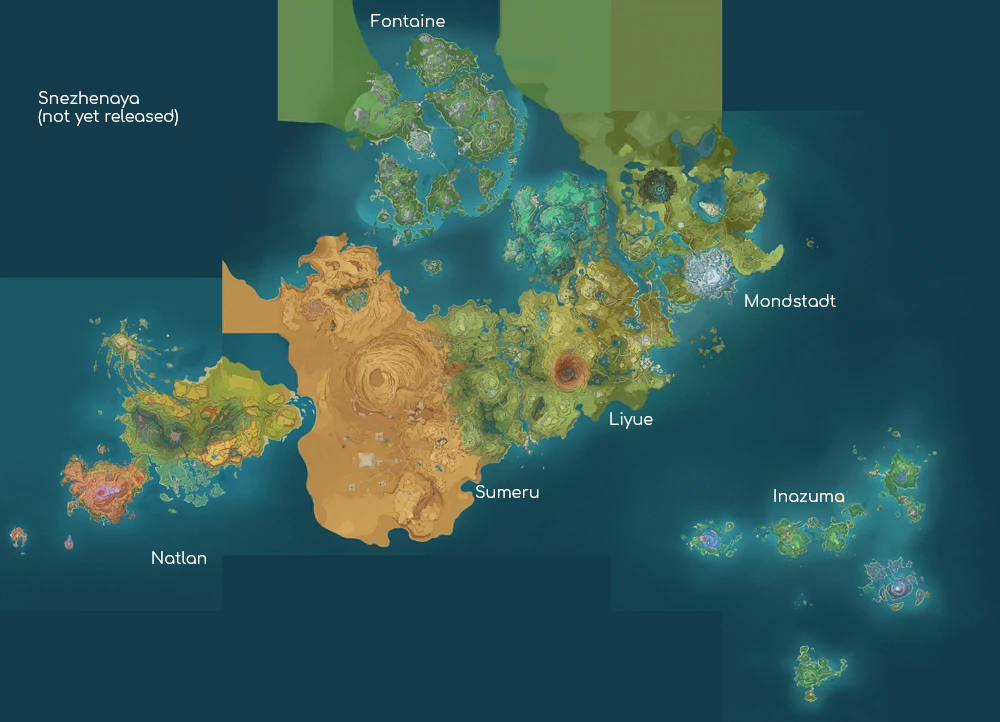

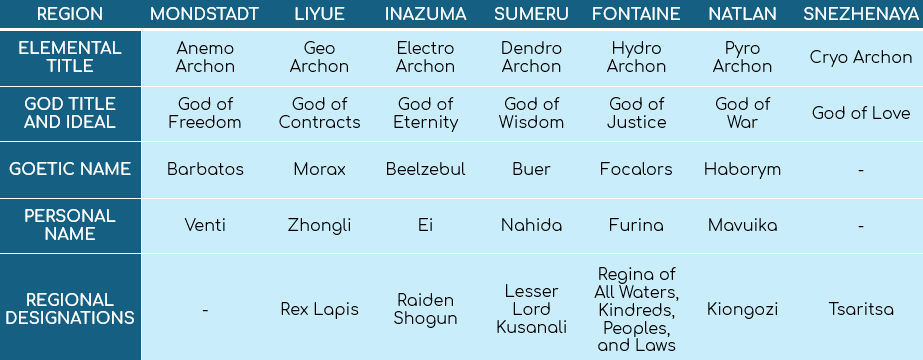

Yet, what seems to be a monotheistic world hides a thinly-veiled polytheistic system. If the inhabitants of Teyvat do worship a single God—usually the one that presides over their region—they also recognize the existence and might of other deities: the Archons.

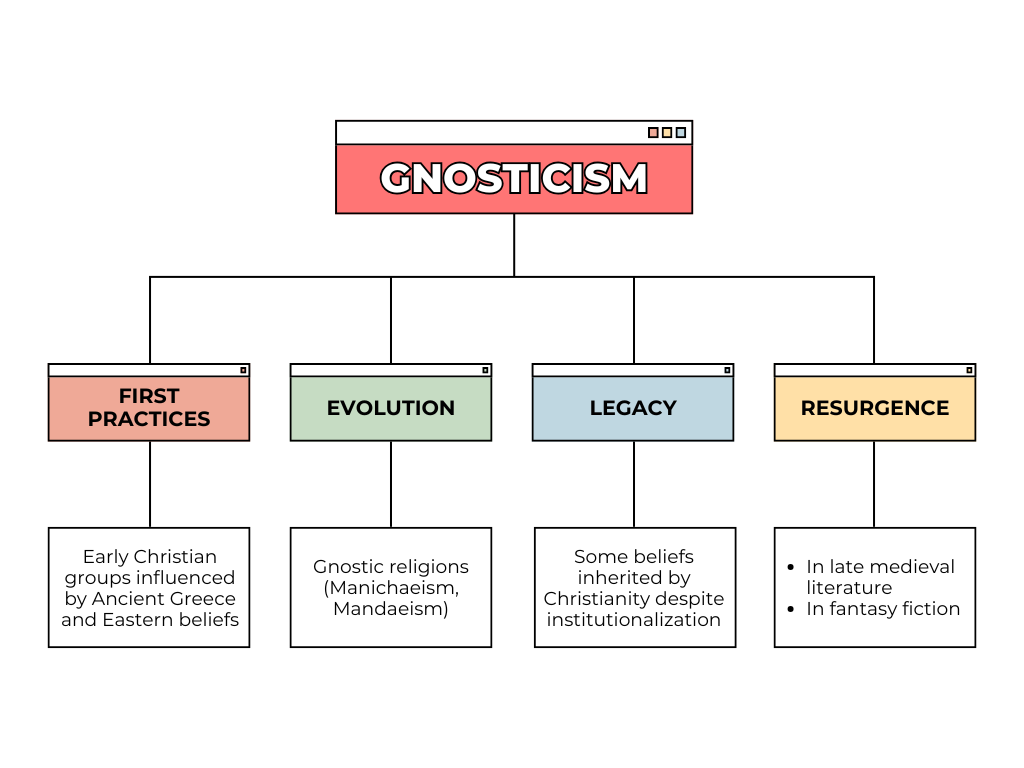

Despite appearances, these deities are named after biblical demons (see Goetic names in figure 4), implying malevolence. Rather than Christianity, such a reversal of order points to Gnosticism, the main inspiration behind Genshin’s worldbuilding. In Gnostic mythology, the Archons are low-level gods that serve not the real god, but the Usurper god, creator of the physical reality. This trope is reinterpreted in Genshin with the leader of the Archons usurping the original ruler of Teyvat. While the Archons are not necessarily evil, they are flawed, prone to mistakes, and closer to humans—thus deviating from a monotheistic conception of divinity.

If the worldbuilding suggests devout faith, the playable characters do not systematically revere the Archons: some can be critical, others can consider them friends, or even be indifferent. The plurality of postures raises questions on the nature of the Archons’ divinity. The Archons themselves supplement this idea, by mingling among humans anonymously, or behaving like celebrities and heads of state. They ultimately all lean towards a godless world where humankind takes over the divine.

This posture aligns with the original acceptation of the Greek term “archons” who were rulers in Ancient Greece. For Hoyoverse, the use of Gnosticism as a source of inspiration allows for the conception of a form of medievalism more fitted to the ever-increasing secularization of the real world. Furthermore, the syncretical nature of Gnosticism renders the worldbuilding coherent. Borrowing from Classical Antiquity, Christianity and countless Eastern traditions, Gnosticism also helps both local and global players familiarize themselves with Teyvat’s laws despite the exoticism related to the game’s multiculturalism. If within Genshin’s narrative, Teyvat’s inhabitants are inclined to break free from the Usurper God, outside of it the players are invited to re-enchant with multicultural fantasy their world brimming with unrest.

Suggested Readings

Campbell, Heidi, and Gregory P. Grieve. Playing with Religion in Digital Games. Indiana University Press, 2014.

De Wildt, Lars. The Pop Theology of Videogames: Producing and Playing with Religion. Amsterdam University Press, 2021.

Elias, Natanela. The Gnostic Paradigm: Forms of Knowing in English Literature of the Late Middle Ages. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Leibbovitz, Liel. God in the Machine: Video Games as Spiritual Pursuit. Templeton Press, 2013.

Thank you so much for this paper, Emilienne! This seems to me like it follows some similar narrative trends to games (or other fantasy medievalisms) that do a monotheistic religion that has replaced (or tried to replace) a previous polytheistic system by drawing on the history of Christianity replacing ‘pagan’ religions, e.g. Game of Thrones’ Old Gods vs Lord of Light. I was wondering if you could comment on the way that this particular inspiration from Gnosticism might mirror or differ from those other texts? It seems like this slightly different model might offer interesting and more multicultural opportunities for fantasy medievalisms?

Thank you for these questions, Tess! There are actually two major shifts in Genshin Impact. The first occurs before the events of the game, with Celestia replacing the Old World. The second is currently unfolding, as humans and Archons aim to overthrow Celestia and restore the Old World.

While the latter clearly parallels contemporary efforts to move away from monotheistic religions, I believe the former only ‘appears’ to reflect how Christianity replaced pagan systems. Although Gnosticism is rooted in Christianity, it is far from monolithic and is rarely considered monotheistic in Asian fiction. The developers actually reinterpret it as a polytheistic system—possibly as a subtle jab at Christianity, and as a way to better integrate Asian spiritualities into medievalist traditions.

Thanks for the paper! Do you have more thought on the specific gnostic elements that inspired the game/is it known that this was a direct influence on the developers?

The element of archons (which I think it’s important to recognise is a slightly more nebulous term than just “ruler”, being potentially “leader” in more numerous nebulous ways) is also interesting. I’m not sure that the element of having several miscellaneously inspired cultures sharing a space with demigod/false-god leaders creates a big novelty in medievalism, that said – that sounds pretty like the role of, say, Vivec and the Tribunal or of the Daedric Princes in Morrowind, which come a good twenty years before Genshin.

Thanks for your question, James!

Elder Scrolls is definitely an influence on later works that reinterpret Gnosticism (such as Genshin.) To answer your question, the developers confirmed that they are not simply borrowing a few elements from Gnosticism, but that it is their main source of inspiration. I’d say they’ve fully reappropriated it as a trademark.

Within the narrative, Gnosticism merges different cultures, while outside the story it blends game worlds and literary genres. For example, Genshin’s medievalism centers on Archons, while their next game, Honkai: Star Rail, which is set in a science-fiction universe, explores Aeons—higher beings in Gnostic mythology.

I agree with your point about the nebulous nature of the term “Archon,” and I believe the developers take advantage of it, as well as Gnosticism’s syncretism to maintain long-term player engagement through the ongoing story.

Thank you for the paper, Emilienne.

A couple of weeks, during the Mythological Game Studies Conference, some of us were wondering which exactly had been the ‘gateways’ for the appropriation of certain historical/mythological tropes related to Western societies in non-Western games. Do you know/have any thoughts about the ‘trope transmission’ of gnostic references in East Asian media? I don’t know much about Chinese games, but gnosticism does appear frequently in Japanese media (e.g. Shin Megami Tensei), and given that Genshin borrows some aesthetic elements from other Japanese games, as well, I wonder if they don’t have a common source?

Thank you for this brilliant question! It’s such a shame I missed the conference; I’d have loved discussing this.

You raise a very good point. Hoyoverse’s original name is actually miHoYo, and their slogan is “otakus save the world.” Genshin doesn’t only borrow aesthetic elements from other Japanese games; it’s deliberately designed to look like one.

I’d say several factors come into play. I believe the 80s saw a rise in interest in occultism—the sheer number of syncretic cults at that time in Japan speaks for itself. Both Tolkien’s and Moorcock’s works were translated and became hits during that period. Shin Megami Tensei was definitely one of the first series to pick up this tradition and in turn influenced later works, such as the Xeno series or Neon Genesis Evangelion. This is particularly interesting considering miHoYo’s constant tribute to NGE.

Rather than the self-reflexive critique of religious tradition we see in Western fiction, I think East Asian media tend to purposefully deconstruct Western notions of godhood and religion—most certainly because of the… complex history of Christianity in Japan.

Thank you very much for your inspiring article, Emilienne!

I am currently working on my thesis related to Genshin Impact, with a particular focus on the Enkanomiya region. Gnosticism also plays a significant role in its narrative, and I found your insights particularly resonant.

I wonder if it might be useful to consider Genshin Impact’s reception of Gnosticism also through its classical reception, particularly with Platonic myth, Japanese folklore, and biblical narrative. This combined perspective could offer a more nuanced understanding of the game’s mythological and philosophical synthesis.

Thank you for your input, Hanjun! Enkanomiya is definitely one of my favorite areas in Genshin Impact; I’d love to read your thesis if you ever publish it.

As you say, they draw from several mythologies, but I believe Gnosticism is the main source of inspiration for Genshin Impact, as stated in one of their interviews on Bilibili. The mythologies used for specific regions do not necessarily connect on their own with those of other areas. This is where Gnosticism comes into play, as it influences every region of the game and allows for the coexistence of these mythologies within a coherent world.

Gnosticism was heavily influenced by the Platonic myth, as well as by Asian spiritual traditions, which, along with the rise of other “heretical sects,” prompted the institutionalization of Christianity. This process was, however, long, and Gnostic elements eventually became integrated into biblical narratives.

Thank you so much for your kind reply, Emilienne! It would be a pleasure to have the opportunity to discuss our theses together.

I also share the view that Gnosticism may serve as a key source of inspiration in Genshin Impact’s narrative. As you noted earlier, the developers were significantly influenced by Japanese popular culture from the 1980s and 1990s, a period marked by a deep reception and reinterpretation of Western fantasy and mythology. In this regard, Rachael Hutchinson’s theoretical work on JRPGs could be a valuable framework for understanding these cultural intersections.

Looking forward to further discussions!

Thanks for the paper! I’ve been doing a deep dive into the lore of the game and I think your interpretation of the Archons is spot-on! What do you make of the primordial dragons or the other “gods” or god-like figures – the Unknown God, Heavenly Principles, Moon Sisters, etc, or of characters like Alice, Skirk, Barbeloth, etc, who seem to come from a world from beyond Teyvat and appear to be even more powerful than the archons, yet go largely unacknowledged by the residents of Teyvat?