By Stevan Anastasoff (Independent Game Developer)

Hello, I’m Stevan Anastasoff, and I’ve been making games of one sort or another professionally for most of the past three decades, but for the past couple of years I’ve been focused on a smaller, more personal project, a narrative exploration game rooted in medieval Welsh literature: Tales from the Mabinogion.

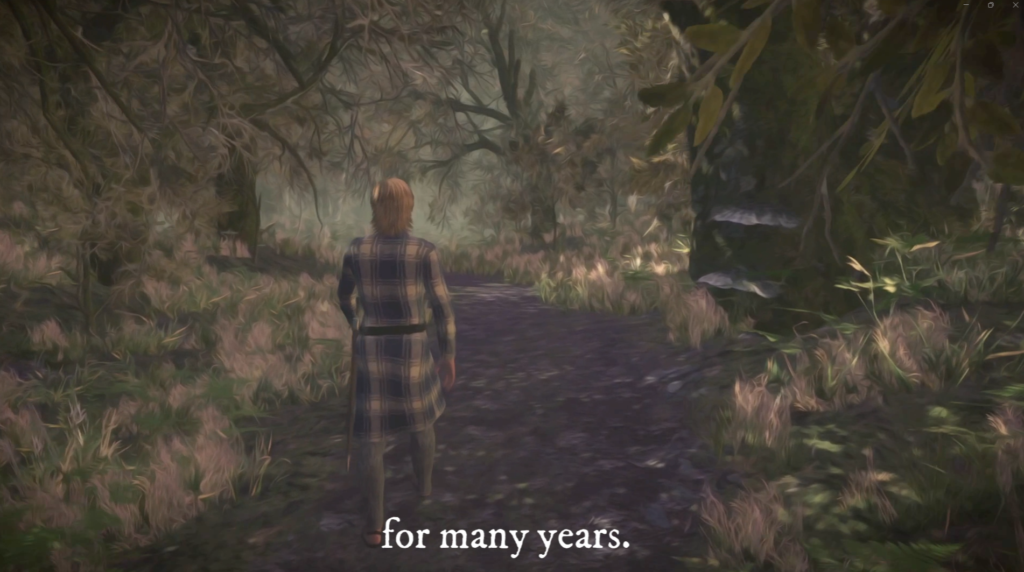

The game itself, which is currently in development, is an atmospheric third-person adventure, that blends storytelling with exploration of the forests, coastlines, and mountains of a mythic Wales. It draws principally on the First and Third Branches of the Mabinogi, using these ancient stories not just as a superficial dressing, but as the foundation of the game. You play as Pryderi, ruler of the ancient Welsh kingdom of Dyfed, returned home to find your land devastated by a cursed magical fog. It’s a game about grief, and forgiveness, about memory, and loss. But more than that, it’s a game about the importance of letting stories speak with their own voice.

When you hear the term “medieval fantasy”, for the big majority of people this conjures images of ancient dragons and powerful wizards, magic swords and mystic prophecies. There’ll be a chosen one, and a dark lord, almost invariably they’ll have British, usually English, accents… We’ve seen it in Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones, Narnia, and plenty of others.

For a game developer, there is admittedly something very powerful about having this common set of tropes. It allows us to step away from the ordinary, but without having to deliver a massive amount of exposition and backstory. We’re spared the need to justify our design choices, in everything from level building, to UI, to voice acting. But this is a version of “fantasy” built on a very narrow view of the past, a view largely perceived through a lens of English language literature and culture, and most notably this kind of post-Tolkien aesthetic that has dominated the genre for decades. We have started to see other cultures gaining ground – with games scaffolded on Slavic, Chinese, Japanese cultures, and others – but most of what we call “medieval fantasy” still speaks with that same voice.

While there’s a lot of strength in that shared language – it makes building worlds easier, it helps players feel at home – it can also box you in. The same ideas, the same emotional beats, the same mechanics start showing up again and again.

It’s not that other types of story are not gameable, far from it. But if you take an Armenian Epic, or a Kashmiri folktale, or a Sardinian ballad, and feed it into the same design framework that’s been tuned for post-Tolkien fantasy, the outputs will all start to look alike. It’s like if the only material your game engine supports is brick, then no matter what you try to build, it’s going to end up looking like a house!

The very first draft of the narrative for Tales from the Mabinogion centered on King Arthur, since many of the oldest Arthurian legends are indeed found within the pages of the original Welsh text. It felt like something players would be able to “grab on to”, a familiar entry point into what is a less familiar mythology. But quickly it felt like this was dragging the story into being something it wasn’t.

In most modern treatments, in games and other media, Arthurian stories come with built in expectations: the chosen one, the kingdom to reclaim, the rise to power. There’s the finding of the magical weapon, often the building of the castle, always the grand quest.

Once you step into that narrative framework, the standard design tropes begin to take over: tracking objectives, doling out loot. The player’s journey becomes a checklist, and the game acts like that’s what a story is.

But that’s not where the Mabinogion leads. There isn’t a main quest-line, with a final boss. There’s no hero leveling up to claim their destiny. The stories don’t build towards triumph. They drift, through grief, and guilt, betrayal and consequence. Conflicts don’t always resolve. Justice doesn’t always arrive. These are tales that offer atmosphere rather than resolution.

So that just wasn’t the right lens to view these stories. Too often what we see is this standardised narrative and gameplay structure being used, with cultural material – names, and styles, and locations – just being layered on top. But the Mabinogion doesn’t work in that way. The tales are older, and stranger, than this framework can accommodate. And it became clear that the way the stories were originally told, would have to shape how I could retell them.

You’ll have noticed something unusual in these game clips, a language that may not sound familiar to most listeners. I’ll come back to that in just a moment. What I want to talk about with you is why I’m choosing to do this, why make a game that doesn’t filter its voice? What happens when we stop designing around familiar, Anglo-centric defaults? What does it bring to the game, and to the player, when you make different choices about the voices that define your world?

And that’s why the game is narrated entirely, and exclusively, in Welsh! Not as a simple localisation option, or a flavour pass, but a core design decision, as fundamental to the game design as the camera or the control schemes. We often treat language as something to bolt on at the end, it’s a part of the localisation pipeline. But that’s exactly what I wanted to avoid. This was the voice that the story already had, and it was only one that could make sense.

When you view it in this way, language becomes more than just the meaning of the words. It becomes a part of the emotional texture of the game, it’s shaping the mood through rhythm, tonality, and cadence, working in much the the same way as a musical score in the background

So this is not just about cultural authenticity for its own sake. It’s a deliberate design decision, a way to create resonance. Inflection, timbre, breath – these things carry weight, just like music or lighting.

In a recent discussion about the character of Geralt, in the Witcher 3, with some native Polish speakers, they shared how they perceived his personality differently than English-speaking players. “The grunts have a different cadence” as one said. Here’s something you can try, a little challenge for you. Take a game like the Witcher 3, which is already one of the more culturally grounded titles in mainstream fantasy, and play it in its original language. Set the voice over to Polish, with only subtitles in your own native tongue, and see what that gives you.

If you’re curious to push it even further, turn off the subtitles completely. Let the meaning of the words fall away entirely, and let the shape of the language alone define your experience. See what it changes, see what it reveals.

The goal isn’t to reject the familiar. There is a real creative strength in working with a shared set of tropes. But as developers, we should be honest about how narrow we’ve let that shared language become. Medieval fantasy, as a genre, has become so flattened by repetition that it becomes difficult for it to say anything new. The settings shift. The visuals change. But the foundations remains the same: the same pacing, the same stakes, and the same voices.

But genre is not something written in stone, it’s not a law of nature, it’s very simply what we’re used to. It’s a habit. And habits can be broken. More and more developers around the world are doing just that, and letting different voices, languages and traditions do more than skin the surface of their games.

And when we do that, we get games that move differently, and feel differently, and stay with players in different ways. We just need to recognise that not every story wants to be told in the same way.

Thanks for this absolutely brilliant paper and excellent start to the conference! I think you make a really good point about different cultural and literary traditions often being a poor fit for (Western) gaming tropes and trends. Do you have a particular example of a ‘drifting’ tale from the Mabinogion? And how have you integrated this into your gameplay and mechanics?

Oh, yes! In the original text you can see that “drift” in lots of different ways: narratively, morally, tonally… For example, often stories may start focussing on one character or story “arc” and then end somewhere completely differently. Or a character may be portrayed as a “hero” in one part of a story, only to be completely reframed as a “villain” in another part of the same story.

The biggest example of this intent in the game is the “fog” mechanic. Very briefly, the fog works like the shrinking zone in a battle royale, but pushing you towards key narrative locations. At the beginning of the game it’s really presented an oppressive force, chasing you through the map. But by the end of the game it’s entirely re-framed as a guide, leading you deeper towards the final resolution of the story.

Thanks! This sort of reframing of characters (protagonists?) over the course of the game sounds absolutely incredible and I can’t wait to get my hands on it.

Hi Stevan! Congratulations on your paper, it was genuinely excellent. Apologies for only now commenting. I completely agree with your point, not every story needs to revolve around kings or chosen ones. Some of the most powerful narratives come from forgotten memories, unfamiliar rhythms, or unresolved truths. Perhaps the real evolution of the genre isn’t about breaking rules, but recognising they were never rules in the first place.

Thx Ricardo, I really like that line “…the real evolution of the genre isn’t about breaking rules, but recognising they were never rules in the first place”…!

Strongly agree with all of this – I’ve been doing quite a bit of thinking likewise about how to “re-tune” the mechanics to better reflect past styles of narrative in games (though my actual game dev work is rather more minimalist and low-grade than yours!)

I kind of feel like minimalist design might _better_ reflect older narrative traditions. One of the first exercises I did was take the classic CRPG structure, and then just start stripping away everything that didn’t feel like it served the story, which turned out to be most of it! (And that also has the added value of making the game easier to make, at least from production and technical POVs!).

The old old adventure game Zork springs to mind – there’s probably a lot of looking back with rose-tinted glasses, but it remains one of my personal most evocative video game experiences. Looking back on it now, the fact that it was so minimal, text only, that makes it feel like I was reading ancient tales, almost stepping into an ancient ritual.

Yes, in my most recent game The Exile Princes I was definitely trying to play around with seeing if you could do a viable strategic layer almost purely through a holding court decisions mechanic rather than the more spreadsheety way most games favour, and I think that turned out pretty interesting for reflecting decision-spaces in a different way (though I still ended up doing chunks of “quest rewarded with gold/xp” and progression as mechanics in that game – I think it’s hard to break every convention simultaneously!)

Oh, and jI ust noticed The Exile Princes is free to play! I have no excuse not to play it this weekend (alongside Pentiment, which I also discovered today and plan on checking out as soon as I get chance!).

Stevan, what we’ve seen so far and your presentation have both been truly impressive. The game’s visual stylization especially caught my attention — it almost resembles a softened, digital reinterpretation of Vincent Van Gogh’s iconic brushwork. This approach seems to merge a postmodern artistic language with a medieval atmosphere. Should we expect to see more instances of this aesthetic convergence as the game unfolds?

Thankyou, that’s a thoughtful take. Yes, finding an art direction was a lot of work! Apart from the need to stand out visually in a crowded video game field, I always feel like realistic rendering is somewhat inconsistent with mythological or fantastical settings. Myth lives in suggestion and symbolism, so visually I think it should _feel_ more like it’s interpreted rather than observed.

Van Gogh was certainly an influence, in trying to get that strong impressionist/post-impressionist brush stroke. A few other influences were David Caspar Friedriech, for that kind of sense of bleak loneliness and awe, George Innes for colour palette, and Kyffin Williams for his capturing of the emotion of Welsh landscapes.

I feel like the way I treat the narrative also ties in to that same kind of feeling… It’s less about treating the text as “canon” and retelling “what happens”, and more about how things are remembered and retold. A lot of the narration is explicitly Pryderi’s memories of events, for example, and a central theme of the narrative is how he reframes those memores.

Thanks indeed for this brilliant paper, and I am incredibly excited to try out the game when it launches. Have you come across any games aside from your own that you think manage to utilise a different (authentic) medieval narrative style from what we’re used to? As a Norse saga scholar I’ve been fond of the Hellblade games for attempting a different form of storytelling based more closely on literary primary sources and medieval lived experiences rather than attempts at historical “accuracy”, but I would love to find more examples.

Thanks for the kind wods!

Inkulinati is one game the comes to mind – but less about trying to recreate a medieval story, more about _living inside_ a medieval manuscript’s worldview. Other games that have been influential in that sort of way are less about the medieval specifically, and more about simply other narrative perspectives, games like Tchia and Never Alone.

And mainstream games are getting way better at exploring more “authentic” material. Even a game like Black Myth: Wukong I think is wonderful, even if it does much the same template (mechanically and narratively), it still great to see more culturally grounded titles from outside the anglosphere! Another one that should maybe be best played with Mandarin Chinese VO, subtitles in your native language!

Thanks for these – I’ll be sure to check them out (as well as Tales from the Mabinogion)!

This was incredible, Stevan, and incredibly well-delivered!

“No King truly rules a land, only the people dwelling therein. The land has no master”

Is this a quote (adapted or otherwise) from your source material? It seems to exemplify a recurring discussion we frequently see in later medieval political writing: to what extent does a ruler actually “owns” the land, and what does that ‘ownership’ entail, if it isn’t absolute.

(Hearing the quote also made me realize how similar Welsh and Irish are. ‘Land’ i nGaeilge is also “tír” 🙂

Speaking of languages and sound, are you trying to achieve a similar effect with your music design/direction? Are there particular references (of traditional Welsh songs etc) you’ve been trying to incorporate in the game?

Many thanks Vinicius!

It’s not a direct quote from any source – that’s a line from the writer I’m working with, Gav Thorpe. But I do feel that it’s rooted in the logic of the text. Authority in power are things that are very conditional – kinship, magic, obligation, and yes the land itself, are all forces larger than the crown itself. The role of the ruler is clearly presented more as steward, rather than owner (at least in my reading and understanding!).

Yes indeed, many similarities between Irish and Welsh in language, and mythology! A fun game is to listen to the “pseudo-arcane” languages used in fantasy movies and TV shows, and try to guess whether they’re actually speaking in Irish or Welsh!

The music is all derived traditional Welsh songs, yes. There’s an interesting effect I’ve noted though… I’ve had a few comments from Welsh people that the music doesn’t sound very “authentically” Welsh. Digging deeper, it seems that’s because “traditional” Welsh folk music has become so associated with voice and harp. But these are both relatively recent (like 18th centur yonwards) developments – much older traditional Welsh music was very different to what we hear now.

I would have loved to have had a soundtrack entirely played on the ancient Crwth and Tabwrdd, but unfortunately intruments and players are very hard to come by! But that’s more the intention for the music, using strings with some percussion to capture a similiar feeling.

I know what you mean! I’ve been having similar issues trying to source period-appropriate music for my late-medieval Irish game, “Galar”.

I really like your solution, trying to emulate the sound of the traditional instruments with modern ones – classical music sometimes does this, to great effect.

This game looks fantastic; I passed your plenary comments on to a Welsh medievalist in my Dept (Siân Echard) who regularly teaches this material, and she was very intrigued.

Thx Robert, and note I’m always open to academic exchange or collaboration, especially with anyone working in teaching or research of Welsh language or literature! It’s really one of the goals of the project to foster dialogue between creative and scholarly approaches to the source material… 🙂

As a student of Welsh mythology, this is exciting. Many will want to learn the Welsh, which helps the immersion experience. The setting is magical and truly another world to explore, yet one which was deep in the consciousness of our ancestors. A stepping back into the world when simple life was a magical life, and a magical life was truth.