By Juan Manuel Rubio Arevalo

Field of Glory: Kingdoms presents a notably nuanced approach to interreligious relations in the Middle Ages—one that stands out among strategy titles. While medieval religiosity is often framed in games through rigid conflict and intolerance, FoG:K more closely reflects what Christopher MacEvitt terms rough tolerance in his study of Crusader-period Levantine societies. MacEvitt’s model emphasizes three key dynamics in medieval interreligious interactions: silence (the overlooking of religious difference in everyday life in written sources), permeability (the movement of people and practices across boundaries), and localization (the centrality of local conditions over broader religious policy). This model is especially useful to approach frontier societies such as the Levant, Sicily, or Hispania

FoG:K nuance to medieval religiosity can be seen in three interrelated element: by distinguishing between local and diplomatic interreligious relations; by simulating the internal diversity of religious groups; and by simulating the permeability of religious practices in some buildings. Religion plays a dual role in FoG:K. Diplomatically, religious differences augment tensions between kingdoms in the absence of a treaty stabilizing their relations. If tensions rise enough, a Crusade or a Jihad might be launched against a kingdom of the opposite religion (image 1). This is an important mechanic, since events like a Crusade was a concrete moment out of the control in the life of medieval people and not a ubiquitous experience.

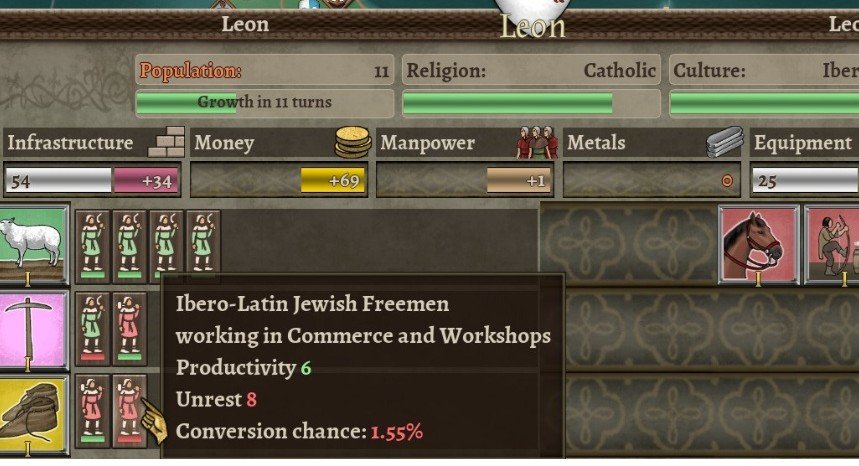

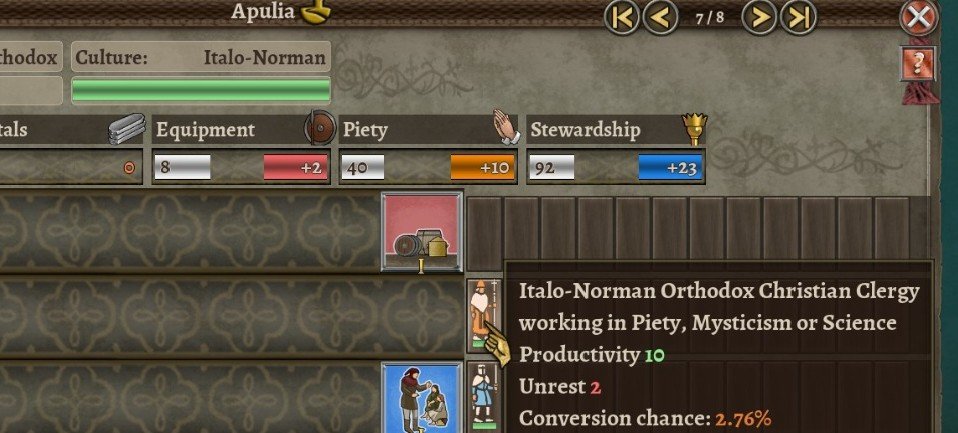

However, the dealing with divergent groups at the local level, while influenced, is not as confrontational as at the diplomatic level. Each region in the game has different types of population, such as peasants, freemen, nobles, and clergymen (image 2). While many strategy games take the presence of a different religion as a neat negative, in FoG:K religion is only one of various factors influencing the behavior its population, including culture, local piety points and religious affiliation (image 3).

Figures 2 and 3

The productivity of clergymen is a case in point, as a priest from a divergent denomination but from the same broader faith might be able to generate piety points (though less efficiency), which does not happen with those of a different religious group. For instance, in the Norman Kingdom of Apulia and Sicily an Orthodox priest produces some piety as a fellow Christian, while a Muslim imam does not (image 4 & 5). This reflects how, in practice, local coexistence could accommodate religious diversity, even amid overarching ideological conflict, as MacEvitt’s theoretical model states.

Figures 4 and 5

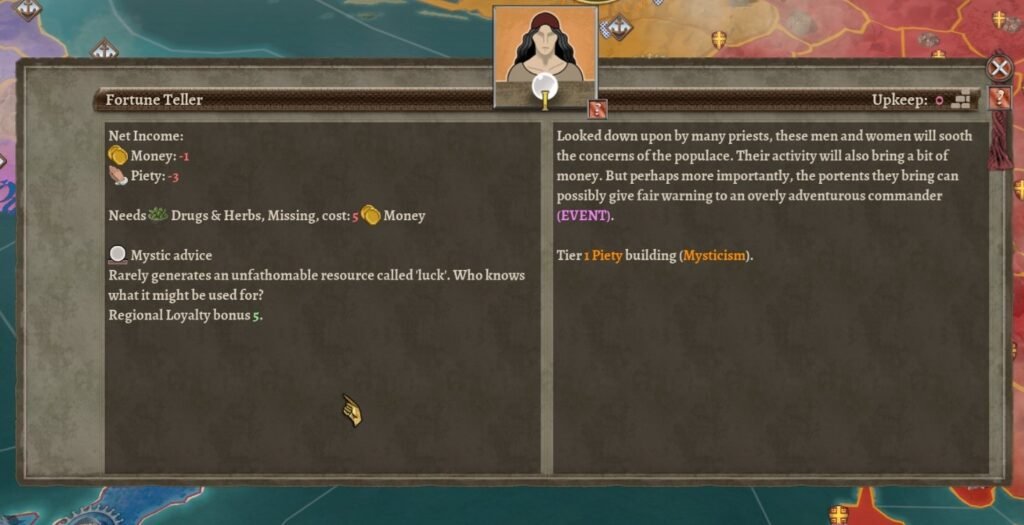

Permeability can also be seen in FoG:K through certain religious buildings. The player might be motivated to build certain structures that might decrease their piety while providing other benefits. A good example of this is the Fortune Teller which, being a practiced condemned by the Church, reduces the piety of the region by three, but provides some income and a local loyalty bonus (image 6). Furthermore, the Fortune Teller comes with a mystic advice mechanic that generates the resource “luck” which can impact stability, conversion, and other events. Such features reflect the interweaving of formal and informal religious practices in medieval life, even when disapproved by Church or secular authorities.

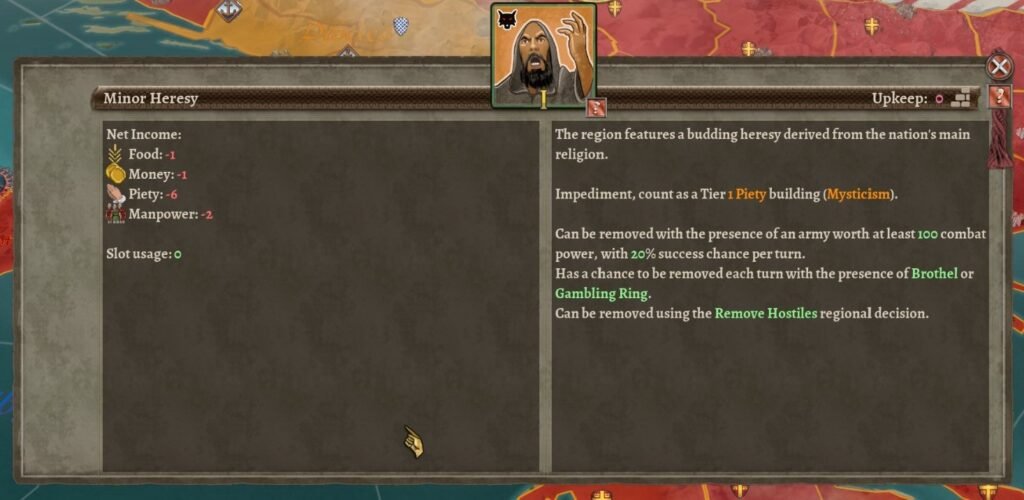

Finally, the treatment of heresy differs sharply from other religious groups. Although religious diversity might cause unrest, heresies actively reduce loyalty, stewardship, piety, and can spread among the player’s territories. This means that while the player can passively convert other religious groups such as pagans or Jews, heretics must actively be rooted out, often through a military intervention. This happens with the building “Minor heresy” which the player cannot manually disassemble but must be done using an army of at least 100 combat power (image 7). This is significant since part of rough tolerance was the negotiation of religious spaces between the authorities and the local clergy leadership of different religious groups, such as Latin authorities and Eastern Christians in the Levant. However, heresy was always seen as subversive of the social order which demanded more drastic measures, like the Albigensian Crusade or the Hussite Crusades show. Unlike other religious groups, heretics were not part of this rough tolerance but were framed as internal enemies requiring violent suppression.

In this short paper I have sought to expose how FoG:K use of layered and dynamic game mechanics offer a nuances portrayal of interreligious life, offering a valuable example of how strategy games can move beyond conflict-based models to reflect the complexities of religious coexistence in the medieval world.

Suggested reading:

Barkai, Ron. El Enemigo En El Espejo: Cristianos y Musulmanes En La España Medieval. Madrid: Ediciones Rialp, 2007.

Constable, Olivia Remie. “Islamic Practice and Christian Power: Sustaining Muslim Faith under Christian Rule in Medieval Spain, Sicily, and the Crusader States.” In Coexistence and Cooperation in the Middle Ages: IV European Congress of Medieval Studies F.I.D.E.M., 23-27 June 2009, Palermo (Italy), Alessandro Musco and Giuliana Musotto., 25–36. Palermo: Officina di Studi Medievali, 2014.

Griffith, Sidney. The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.

MacEvitt, Christopher. The Crusades and the Christian World of the East: Rough Tolerance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Moore, R. I. “Heresy, Repression, and Social Change in the Age of Gregorian Reform.” In Christendom and Its Discontents: Exclusion, Persecution and Rebellion, 1000-1500, Scott L. Waigh and Peter D. Diehl., 19–46. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

———. The War on Heresy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Rist, Rebecca. “The Medieval Papacy, Crusading, and Heresy, 1095-1291.” In A Companion to the Medieval Papacy: Growth of an Ideology and Institution, Keith Sisson&Atria A. Larson., 309–32. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

First of all: thanks for the bibliography! I’ll definitely be adding some of these references to my medieval history course next time I teach it.

Implementing religion is an interesting topic in games, because we always run into the issue of translating immaterial notions into discrete and quantifiable variables. E.g. ‘luck’ being something that has a tangible, quantifiable effect on a polity. What’s your take on how FoG: K handles this task? Especially in comparison with other strategy franchises out there?

I really liked the use of luck as a religious mechanic in the game. Most strategy videogames tend to use religion as an indicator of public order or a way to determine how much money or which units the player has access to. This tends to place religion into a more utilitarian perspective, which kind of puts aside the importance of actual belief in daily life. While FoG still does some of this through the unrest mechanic and the incentives for religious and cultural conversion, mechanics like “luck” force the player to consider how non-orthodox practices and beliefs influenced the lives of medieval people, like surviving a battle or an assassination. I think this nicely communicates that while Christendom was dominant, the Church did not have a monopoly on popular spirituality, neither for common people nor rulers.

This is some really interesting discussion Juan. It’s always good to see a more nuanced model towards religion, but does the game do anything to facilitate or even encourage maintaining a multi-religious kingdom? Or are co-religionists always more productive and less rebellious? Are there any other examples of a benefit to keeping quasi-heretics (like the fortune teller) around?

Thank you for your questions Rob. The religious mechanics in FoG: K were a nice surprise, especially when one compares them with other titles that often understand it as homogeneous and confrontational. I would point out two issues regarding your questions. The first one is that FoG still encourages the player to impose some sort of uniformity in the player’s realm through the unrest mechanic; however, different from other titles like Total War, the game provides more tools to do this beyond simple religion, with culture and the authority and characteristics of the ruler being good examples. In this way, the game is not encouraging the player to hold to a multi-religious polity, but it provides other tools so that such a polity might exist without being a net negative for the player.

As for other examples in keeping non-hegemonic religious buildings, two examples come to mind. The first one is the Seer, which is the second tier of the fortune teller and works in essentially the same way, but the player loses more piety (-8). The other examples are the Astronomer Study and Astronomer Workshop, which reduce piety while increasing legacy points and bringing in some money. While these are not heretics, it does communicate a conflict between modern notions of science and religion, which says more about our understanding of science than medieval perspectives on the role of religion in knowledge.

Thank for this intriguing paper!

The idea of ‘rough tolerance’ actually applies quite well to FoG: Kingdoms. The religion system of the game, with broader faiths including more than one denomination, clearly resembles that already implemented in Crusader Kings, but one thing that shines here, as you (rightly) highlighted, is how FoG tries not only to represent the effects of having different denominations of a broader faith in a single realm, but also the influence (and usefulness, from a ruler’s point of view) of practices which do not fall into the ‘orthodox’ field.