Figure 1. Falcon in flight (CC Tony Hisgett, 2011)

Early medieval law codes offer an excellent resource for inspiring and informing the settings of Tabletop Roleplay Games (TTRPGs). For several years now I have been idly working on such a project, Langobard, inspired by the first written Lombard law-code, the Edictus Rothari issued in 643 CE (edited in the modern day as: Bluhme 1868; Azzara and Gasparri 2005). This paper looks specifically at the Lombard laws relating to apes [bees] and, in particular, acciptres [hawks, falcons], which inspired a range of Skill traits for the game (especially beekeeping and falconry/hawking); entries for the Bestiary and Inventory chapters, and informed on the early medieval landscape against which the stories unfurl.

Falcons cannot be reared in captivity, but must breed in the forests and then be captured young and then trained by a would-be falconer (Forsyth 1944, 253–56). It is presumably against such a backdrop, that the Lombard laws consider the taking of falcons from another person’s forest or royal property, or else from a nest in a marked tree (Rothari, §320-21: Bluhme 1868, $).

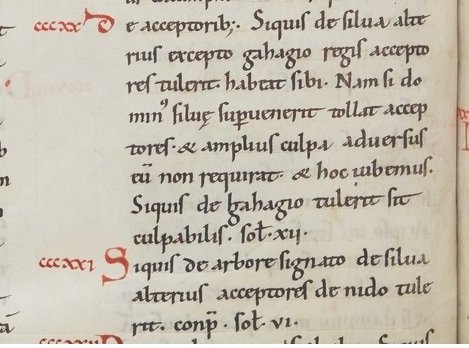

[§320] If anyone takes a falcon from someone else’s silva [wood, forest] they may have it, except in the king’s preserve. But if the lord of the forest comes along, he may take the falcon and no further blame will be imputed to him…

[§321] If anyone takes falcons from a nest in a marked tree in someone else’s wood, they shall pay six solidi as composition.

(Translation emended from: Fischer-Drew 1973, 114–15)

I shall return to the ‘royal preserve’ (and the bees) in the fuller version of this piece; today, we shall focus on the implications of falcons taken from the silva [forest] belonging to another person. The legal framework here is somewhat complicated, as are the implications for landscape, ownership and access. But fundamentally, we can see forests owned by other people, in which certain trees would have been marked, indicating that the owner had previously identified the presence of nesting falcons (or, a hive of wild bees, per Rothari, §319), and intended to return to later when the fledgelings were mature enough to be captured and trained. Otherwise, where a tree with nesting falcons had not been identified or marked, the would-be falconer could take them freely — assuming they can get the bird out of the forest before the lord spots them, and relieves them of their hard work!

More than just a geographic landscape for our plot to unfurl on (that is a specific forest with specific trees, some of which contain nests with falcon fledgelings, one or more of which might then be captured… with intent and appropriate dice rolls) the geography is enriched through these interconnecting webs of social and legal ownership, restrictions and permissibility. Effectively, a “law-scape”, that can result in further twists and turns in the plot and interactions with other characters, arising from ownership and access, what was permitted, forbidden or deemed ideal (regardless of whether it was enforced, enforceable or imaginary) and what actions and responses the legal actors, that is our player and non-player characters, might then take in such situations.

Players in the TTRPG, through their characters in the story, center human agency in response to the sometimes dry language of the laws, and opening an analytical dialogue with them. A game of Langobard might well see our players find a falcon in the woods, and while they may well lose the bird to the owner of the woods, hopefully they will also emerge with an enriched and empathetic view of early medieval laws and how they might play out on the law-scape.

Bibliography

Azzara, Claudio, and Stefano Gasparri, eds. 2005. Le leggi dei Longobardi: Storia, memoria e diritto di un popolo germanica. Rome: Viella.

Bluhme, Friedrich, ed. 1868. ‘Edictus Langobardorum’. In Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Leges, 4:1–205. Hannover: Hahn.

Fischer-Drew, Katherine, trans. 1973. The Lombard Laws. Cinnaminson, NJ: Penn: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Forsyth, William H. 1944. ‘The Noblest of Sports: Falconry in the Middle Ages’. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 2 (9): 253–59.

ALT TEXT FOR IMAGES

Figure 1

Close up image of a falcon in flight against a clear blue sky, beak open, tail fanned and wings at a steep angle, it looks like it is just about to dive in the hunt for prey.

Figure 2

A logo reading “Langobard a roleplay game” The background is black with a heavy burst of golden and amber flames which rise diagonally behind the line of text, and glints on the metallic font used for the title.

Figure 3

Two laws written in black and red inks on greyish parchment, taken from a tenth-century manuscript of the Lombard laws. In the margin to the left, red ink is used for the roman numerals of the capitula numbers and the pen-drawn initial letters introducing each law. The laws themselves follow to the right in a Late Caroline Minuscule script, written in black ink in eight short lines for the first of the laws, and a further three such lines for the second.

Figure 4

A landscape photograph of a scene from Trentino, Northern Italy. Under a blue sky, grey mountainous peaks rise to left and right, with the hint that there might be a pass between them in the centre. In the middle ground, forests of coniferous woodland rising up the lower slopes of the nearer mountains, and bordered at the front with the line of a (modern-looking) fence, while the foreground includes a wedge of open meadow.

Fascinating! Does this imply that there were standardised (and thus fully mutually comprehensible) “falcon marks” of some kind?

Hi James, thanks – and thanks also for the great question! Sadly, this is one where I’ll have to prevaricate, as the laws simply don’t give enough fine detail here to be able to answer with certainty whether or not the marks were standardised. Nor if there were specific ones for falconry, and for other purposes.

I’ve always assumed that it would be more than just an or similar, and would also convey information about the person who made the mark, or why they marked that particular tree. But that’s not the sort of thing that got written about in the laws, or historiographies. So our best hope would be if any such marks on wood have been preserved archaeologically.

What the laws do say about marks is in itself interesting, though:

The first time they appear are a bit earlier in the laws, in Edictus Rothari, §238–41, with the first two of these addressing the situation when a free (§238 ) or enslaved (§239) person/man cuts down a marked tree which designated a land boundary. A compensation of eighty solidi (equal in value to about 360 grams of gold), to be paid half to the person whose tree it was, and half to the king (possibly the local representative of the royal court, rather than directly to the king), In the case of the enslaved person, there’s a death penalty for the same act, but commutable with a payment of forty solidi. In both of these cases it’s explicitly for boundary marking, and it’s somewhat unclear if that could be applied to cutting down a tree marked (say, to show that it has falcons nesting in it!) within another person’s forest. That might just come under cutting down another person’s tree (which I’ll talk about in the reply to Vinicius’ comment, so I don’t write it out twice and turn this reply into another paper)(It’s… already another paper, isn’t it)

The next two laws are particularly interesting, as they talk about the act of marking a tree within the woods belonging to another person. Both Edictus Rothari §240 (freemen) and §241 (enslaved) use the same core terms here: signa nova [new marks, signs] which are called ticlatura or snaida. Fischer-drew translates the latter two as “notches” and “carvings” respectively, perhaps suggesting a degree of complexity in the mark from a simple cut to something with more detail. In which case, that would at least hint at specific patterns being used to convey information beyond just “this tree”. I don’t have access to proper reference materials at the moment (I’m writing this on the train), but however, it looks to me like ticlatura are “notches” or “ticks” in Latin, while snaida looks distinctly Germanic. So I’m assuming that what we actually have here are words for the same thing in the two languages which were in use, Latin and Langobardic. This is a pretty common approach throughout the laws, with a lot of the Langobardic legal terms for specific crimes being given a Latin counterpart as explanation, and offering a really useful insight into how law and society must have been envisaged at the time.

There’s also some interesting exceptions hinted at in those laws of course: does the explicit statement that it’s only crime to make such marks on a tree in somebody else’s forest just imply that of course it’s ok to do it in your own forest? Or is it implying that there are forests out there unowned by anybody, but a person can then come along and claim an individual tree for the long.term resources it might provide:

Those long term resources, of course, are things like the falcons in the marked trees of Edictus Rothari, §321, and the wild bees in the marked trees of §319.

We’re going to have to put this on the gaming table, and see how it unfurls!

I’m envisaging an elaborate falcon heist, thwarted when the bird wrangler rolls a critical failure on their ornithology check, and the gang of arimanni end up with nothing to show for their endeavour but a common wood pigeon…

Have you had anything like this play out in your sessions? How do you get players invested in the laws and morality of the period?

Hi Rob, thanks for the comment and questions!

I’ve not yet had a chance to play test the falconry rules – beyond using characters out falconing as a means for them to stumble onto the main plot hook. Currently I’m still working on that section, and when it comes to playtesting I keep running a specific scenario that I’ve been writing, about magic and the possible striga, which is more a vampire than a witch in this period (and the foundations of which i discussed at MAMG 4).

But, yes, I’ve definitely been imagining heist scenarios for this! And hoping to run something soon. I’ll be honest, that I’d not really thought about the potential of a misidentification-of-birds outcome before, but honestly that would be perfect – and probably quite likely as well…

One of the other, related questions that plagues me, and could be fun to test out in game, are how far from the tree with the falcon do you have to get before the lord of the forest can no longer claim the falcon for himself? I always imagine him waiting at the bottom of the tree, as the would-be falconer climbs back down. But perhaps that right extends throughout the forest owned by the lord. What if that lord also owns the open farmland between the forest and the settlement that the falconer’s heading to, and that’s where the lord catches up with them? What if they’re caught up with when they’re off the lord’s land, but on their way home? Or just back to their home when they are caught. I suspect a lot of this comes down to the personalities involved, including those of the legal officials!

Gaming those scenarios as research questions in a TTRPG runs the risk of simply revealing what the players think, especially if they’re less familiar with the broader contexts of how early medieval laws approach comparable situations. But when one or more of the players has relevant information, then the collaborative theatre of the TTRPG definitely acts as a useful medium to bring it into consideration as a working hypothesis. And gaming it tends to throw up a lot of unexpected perspectives on the overall situation. Which is where I think one of the great benefits of the TTRPG as a vehicle for thought experiment comes in.

As to the question of getting people invested in the laws. That’s a good question, as I’m still very much in the ‘informally play testing a partly written pieces’ phase, my audience so far has come pre-invested. 90% of the play tests so far have been at conferences, with medievalists responding positively to the question of do you want to play a TTRPG set in the Lombard laws? So I’m going to need to be careful if (when!) it gets in front of a broader audience, to make sure it can excite people about the law as well as the game.

For now I’ve used a couple of strategies to relate the setting and/or plot to the law:

1. Indirectly. This is the sandbox, open world approach. The setting is inspired by what the laws say about early medieval Italy, but the characters are just moving about in the world living their lives rather than directly facing the law. As a rule, this has tended to spark curiosity amongst the players, and game will frequently get paused to answer questions about the sources underlying something that has snagged their attention, or else to suggest a relevant source or comparison – but again, the players here were themselves medievalists, so that came naturally! Also, I’ve mostly used this approach when I’ve just been wanting to test the rules engine itself, as I decided to make my own from the base up, rather than making the game just as a veneer on Chaosium’s Basic RolePlaying (which would have been my next choice) or some other published system, such as D&D 5E, etc.

2. Bait and Switch. This has usually developed during one of the previous, indirect types, and tends to happen when the characters are getting into a situation that I can see as being directly law-related, but the players haven’t realised yet. In these cases, this is usually because the Otherness of early medieval law contrasts with the assumptions of the players. In which case, I tend to start laying traps for the players to walk into and trigger the law, and then reveal it as a dramatic aha! moment. The best example I have of this to date, was when my players kindly grabbed a horseriding freeman who was about to tumble backwards over a low cliff, dragged him from his horse and saved him from potential injury or death. But! I then had my NPC take affront at the crime of marahworfin – being thrown from his horse – that had just been committed against him. The social humiliation now out ranking the potential harm he could have suffered. So it turned into a great teaching and discussion moment.

2b. I realise that in some quarters this kind of tricking the players to get the characters to do something can be considered a little unsporting. And sure, I could have made the players make relevant rolls on their law skill to see if their characters’ knew the legal risks. But, just like with a failed perception check, saying that what they were planning “as far as you are aware it’s legal” would have prompted them to the impending danger as much as rolling a success would. But I had been thinking about introducing more story-gaming rules into the setting, so that players know the rough shape of immediate outcomes before they commit to the action and roll, and are at least as informed as their characters would be in the situation. But the falconry laws have given me a counter to that. The statement in Rothari, §320 that “no further blame will be imputed” to the person who was discovered taking the falcon strongly suggests to me that many a lord did impute blame on the person they discovered taking a falcon from their woods, even if the tree was unmarked. Blame which may have been pursued as a law-case, accusing the person of theft, or just giving them an immediate beating on the spot. Again, all fuel for specific plots – but it’s also a reminder that the ‘bait and switch’ approach probably happened to people in the early middle ages, when they assumed they knew what their legal standing was (or when the law-case was found against them even if they were in the right…). People in the modern day frequently break laws unwittingly too, afterall. And the emotional roller coaster of a bait and switch is part of storytelling, but the incongruity also helps people remember the laws (and other sources) and become invested in them. So my current view is that the ‘bait and switch’ is both a benefit for all aspects of the TTRPG from entertainment and representation of the medieval, through to teaching and research, and also is justifiable from the source materials. So I’m re-working the rules to encourage it.

3. Investigative. In this type of story the characters are actively investigating or pursuing a specific crime that has occured. As such, the law is at the forefront, and the players (hopefully) become invested in the law as they match the circumstances they are encountering against the definition of the crime as written in the law-books, and as they pursue the case through the various relevant Lombard legal institutions (making the accusation and defence, oath swearing, trial by combat or ordeal, payment of compensation, etc. etc.)

Also, another way of getting players invested in the law is already at play during character creation. To get the initial spark for their character concept, players ideally should go through the Lombard laws and identify laws that have or will influence their character. This can be something as simple as the laws on injuries determining a wound that the character has encountered, or as vague as reading specific the legal details for a freewoman in the case of a specific crime and saying, Iwant to play a free woman, or highly detailed and specific – an inheritance dispute arising in relation to an unmarried daughter who still lives at home, with sisters who are married. (although that particular law is from the eighth century…) The players chose two or three laws to inspire the character, and get awarded Experience Points at the end of each session for roleplaying/pursuing their connection with that law and bringing it to the table.

Oh wow, thanks for this Thom! I like the bait and switch approach (and can see a similar ‘damned if you do…’ set up where the players get into different sorts of legal trouble no matter what they do) but agree that it’s maybe a bit unfair. I suppose having the players as representatives of NPCs who’ve fallen foul of this could be interesting too.

I’ll have to think some more on this, I’ve been trying to get players to play the character not the game a lot recently.

You’re welcome! i may have gotten a bit heavy into writing replies 🙂

Yes, I think having a very open world approach to how characters can interact with various crimes nad legal processes is vital to keep it fresh. I was taglining the game a coupel of years back with a phrase along the lines of it being about “investigating crimes according to the Lombard laws – or committing them!”

On the old threefold model (forge theory) of players tending to prefer either narrativist/dramatist, gamisr or simulationist approaches to TTRPG play, I definitely belong to the former! That actually left me struggling with the feeeling for a while that writing a game about the Lombard laws was fundamentally “simulationist”, and at odds with me and my preferences. And then, a bit of time how do i make it so that all sides are welcomed.

Now I’m thinking much more in terms of the two sides of narrativism, and comforatably centering those, without actively excluding the others. As a GM, I tend to gravitate towards character led plots. I’ve also found having a “motivations” trait in Langobard has really helped with getting character-led approaches onto the table, and as a way of getting players to think about the impulses htat drive their characters towards the logic of irrational/suboptimal behaviour. So the charactersheet has a list of motivations (derived from impulses named in the laws), such as “anger” for where a laws says “if x was done in anger”, that players then select a few of. that gives them a list of things that they are particualrly suceptoble too. But at the same time, in rules terms the player can state whey that emotion helps them in a given action, and adds an a extra dice tthe dicepool (but can also raise the difficulty level of the target they have to beat with the dice roll, if it seems like the emotion would hinder).

While it could theoretically feel a litle too much like “roll-play” to mechanise the motivations this way, i feel in practice that it works more as a dramatist prompt.

But, yes, getting players to play the character and the scene over the game can be difficult, and its something i’m thinking about a lot too (and am meaning to spend more time reading about ‘historical empathy’ approaches, for sure!)

Not gonna lie. Judging by the title, I thought the paper was going somewhere else XD

This is super interesting, and it touches on a topic (relationships of medieval societies with nature) that I’m starting to get into lately.

Two questions:

1- There has been some reevaluation of medieval law codes within ecocriticism lately. Some people have argued that medieval or ancient norms could serve as inspiration for a more sustainable way of being in the world in the Anthropocene. E.g. there’s a tree list in the Irish law tract called Bretha Comaithcheso that argues that trees were afforded a ‘wergild’ of sorts, with people having to pay a compensation based on the species of tree that was damaged or destroyed. Some people have tried to argue that this was an evidence of some sort of ecological conscience, etc etc.

Is there anything in the Lombard law-scape that, in your opinion, supports a similar parallel? Is dealing with this anachronistic (but potentially interesting) readings something you’d be up for exploring in your game?

2- This one’s a comment, actually. There’s been some avant-garde work in game studies lately that are trying to question the “humanness” of human players. This goes from critiques of the liberal-humanistic bias in our conceptions of individuality to more overt posthuman readings of inter/intra-actions of people and machinery/non-humans. Cf. e.g. https://gamescriticism.org/issue-6-a/

The concept of a “law-scape” sounds very interesting to me as an opportunity to discuss these ideas in a game. After all, you seem to be dealing with a source material that in some ways seek to arbitrate the boundaries of human intervention on nature. The fact that Langobard is a TTRPG makes it even more open to these sorts of subversive ways of playing.

Hello Vinicius, and thanks for the comments and question!

Well, I must admit I couldn’t resist the pun when the opportunity presented itself, and didn’t mind luring people in on false pretenses (another means which I should add to my reply to Rob on how to get people invested in the laws… 😉 Long story short, I realised when researching the paper, that the comparable laws on taking bees (and/or their honey) from marked trees in the royal enclosure provides a counterargument to the image of Rothari as the “great royal falconer” that has been imputed on the basis of the laws on taking falcons form the royal enclosure – that in the end i just couldn’t fit into the word limit here. But I’ll return to it in the (near) future… And I really look forward to seeing more of your research on the relations of medieval society with nature, I’ve found that that is definitely a recurring theme when gamifying the laws! And yes, laws definitely arbitrate that boundary (and others), so playing along them is a valuable tool for exploring how it might be framed and how it could work.

On to your questions:

Firstly, yes, I do like the Irish tree laws which i’Ve skimmed through a bit in the distant past, and really keep meaning to re-read them with more detail at some point. There is something which, I think, is at least superficially comparable in the Lombard laws, as we have values of compensation outlined for cutting down different types of trees belonging to other people. It’s not given specifically as wergild (or widrigild, as it is usually spelled in Langobardic), nor with the Latin counterpart praetium [worth]. Instead the laws simply say that the damage has to be conponat [compensated]. So my first thoughts here are that the trees aren’t being framed in human terms, but rather as the property of their owner. but i need to spend some time reflecting on that to be certain.

What we do have are three laws, addressing different trees:

Edictus Rothari, §300 sets compensation of two tremisses (i.e two thirds of a solidus, or equivalent in value to about 3 grams of gold) for cutting down either an oak tree or a beech tree, and gives names for them in Latin and there Langobardic parallels (again, i don’t have good reference materials on me at this moment, but as far as I can tell now there is one Langobardic word for oak “rovore” and two words in Latin “which is cerrum or quercum” and then two Langobardic words for beech “modola [or] hisclo” and with one word in Latin “which is fagia”. But I really should double check that! Oh, and these laws only apply for trees within an enclosure and its perfectly acceptable for a traveller to cut down another person’s tree of this type for their own use, if it outside of an enclosure – again, there’s a lot to be considered here on the interactions with nature, law-scape and landscape, and I think the phenomenology of travellers and residents.

As I understand it, the acorns and beechnuts of the two previous tree types can be eaten – if things get bad enough – they’re usually used as mast for pigs and other animals grazing in the forests – hence, I assume the mention of them being within an enclosure, so that the pigs don’t stray from where they are meant to be foraging (I don’t have the specific reference to hand, but Paulo Squatriti’s discussion of chestnut trees in his Landscape and Change in early Medieval Italy, talks about enclosure’s used to keep pigs out from the areas where the chestnut trees are, at least until the chestnuts have been harvested, so as to prevent the pigs from happily gobbling them

With Edictus Rothari, §301, we move to more appetising fruit and nut bearing trees: the just mentioned castenea [chestnut], as well as nuce [hazelnut], pero [pear] and melum [apple]. Here the compensation due increases to a full solidus (roughly 4.5 grams of gold).

Then finally we have Edictus Rothari, §302 for the olivo [olive tree], where the compensation triples to three solidi (equal in value to roughly 13.5 grams of gold). While not a tree, another expensive (delicious) fruit-bearing plant that is addresses is the grape-vine: with a compensation set at either six solidi for killing it by taking more than three or four stalks (Edictus Rothari, §292) or just one solidi for deliberately killing it by digging it out of the ground (§294). I’m not sure why there is such a great difference in compensation between the two crimes here, so I really need to reflect on that too. Probably within a TTRPG setting of a faida [feud] between two families across some beautiful Tuscan vineyards and olive groves!

Secondly, thanks for the link and the questioning on humanness in games. That sounds really fascinating stuff, and I look forward to reading through it. I’ll have to see how it fits in, I guess from the law perspective there are two questions: one, to what extent are enslaved people dehumanised, and secondly, if and to what extent do we see the (legal) anthropomorphisation of the non-human. a third element of course would be the non-human/humanoid monsters that sometimes get mentioned, such as the striga, and from my main work on the PresentDead project addressing human interactions with the dead in the early medieval period, if and how people become non-human after death, and if and how they can retain/be returned to a human status.

Great stuff as always Thom!

I really liked the idea of dealing with human-animal interactions in the specific legal system of the Lombards. If I may, I would like to exploit Vinicius’ latest comment concerning the “law-scape”: I agree with him that is an interesting and intriguing concept. More so: I think the idea of a “law-scape” could serve to actually go beyond the idea of human intervention on nature, and to see early medieval law codes as fundamentally tools for shaping, or re-shaping, networks of which the nodes are, at the same time, made by humans and elements of nature. Let me explain by an example (and please, Thom, correct me if I’m wrong): in Lombard law, a forest, or a pasture, become visible only if they are owned by someone, including the king. The same could be said of animals, and so on.

This could pave the way for a novel representation of players and their relationship with space in games set in the Early Middle ages.

Hello Arturo, and many thanks for the kind words and for the question and comments!

Yes, you are absolutely right that law-scape is bigger than just the human:nature interface, and can interact with all manner of the legal landscape, both within settlements and beyond, and from the level of within a single room to perhaps the entirety of a regnum or empire or continent or world… it has to be scalable. I initially started using the word when presenting a paper on the different levels of judicial district referred to in the Lomabrd laws (or inferred into for the seventh century , in the case of the sub-territory of the sculdtheis [local legal official] within the iudicaria or civitas as overseen by a judge.

I think I agree that the idea of territories only becomes visible when in relation to ownership, and then only in abstract terms so that the socio-legal category of pasture or forest, etc. can then be applies to any specific instance. The unowned arguably only becomes named when it is being claimed. There’s a further layer to add (which I hinted at in some previous replies to questions and which keeps cropping up in my history of law research) in which the things which are deliberately left unsaid in the laws are as important as those which are said. and there’s a lot of analysing the ‘negative space’ required to understand the scope of the laws – and yes, the TTRPG and other gamification modes are really valuable tools through which this can be explored!

Legal context typically makes for some very compelling plots, as navigating “law-scapes” (as you put it so nicely) is the meat of many detective and mystery plots; and at the same time, they engage in a complex form of world-building given the centrality of law codes to how societies function.

Legal context typically makes for some very compelling plots, as navigating “law-scapes” (as you put it so nicely) is the meat of many detective and mystery plots; and at the same time, they engage in a complex form of world-building given the centrality of law codes to how societies function.

Hi Robert, Many thanks for the comment and the kind words!

I’m glad you like the “law-scapes” concept, I’m finding it really useful for thinking about how the legal world is imagined, and the ways that crimes and investigations into them might be geographically framed, and certainly how divides like public|concealed can play out, and how information can feed into gossip communities.

As a TTRPG player and storyteller, I tend to be much more a “theatre of the mind” type, but researching into the ‘abstract geography’ of the laws is getting me steadily closer to thinking about maps and physical modelling: “unmappable maps”, maybe, at least.

And I definitely agree that law offers rich and wonderful plot hooks for crimes that players can investigate and uncover – but I also like to to give them the opportunity to commit, conceal and deny them too!

As Wormtongue might put it, forgive my tardy entrance, clearly I’ve chosen a most inconvenient hour to conjure a reply! But I really wanted to thank you for such a rich and thought-provoking reflection, Thom. The Langobard TTRPG you outline brings early medieval legal cultures to life in a way that’s not only mechanically engaging but ethically resonant. It’s those seemingly small choices, like whether to claim a fledgling from a marked tree, that reveal just how entangled law, landscape, and personal agency can become. In moments like these, the moral stakes of the world emerge most clearly, sometimes more powerfully than in the grand, heroic arcs we tend to expect from roleplay.

oops, I wrote a response to you, but posted it as a standalone comment rather than putting it here as a direct reply (sorry!).

Please find it below!

Well… I think i may have just written in the comments a good half of the chapter(s) on forests and falconry that I’ve been planning to work on 😉

Hello Ricardo, and many thanks for the kind words and the commentary.

Yes, I agree entirely that stories can be dramatic and fulfilling with smaller stakes, and we don’T have to make everything epic (that said, I’ve had some epic stand-offs in playtests of the Langobard TTRPG too!!).

And, yes, the framework of the TTRPG really allows player agency to be centred, so the seemingly small ethical question of whether to take the fledgeling from the marked tree or else spend the time to try and find another (thinking about the falconry mechanics in GURPS for a moment, the 4E basic set states “finding a wild falcon’s nest in spring requires a week’s search and a successful falconry roll” (2020: 194) which sounds about right. so assuming I were to introduce a comparable timeframe to the mechanic for the Langobard TTRPG, it’s quite easy to imagine a character spending failing to find any over a couple of weeks of unsuccessful searching, then being increasingly tempted by those chicks in a marked tree that they just happen to keep on passing…

Small choices make big stories!