By Baykar Demir (Istanbul Bilgi University)

Introduction

This paper explores how modern medievalist video games integrate art historical motifs to create immersive representations of the Middle Ages. By analyzing Kingdom Come: Deliverance II, this study examines how medieval art, architecture, and iconography are used to shape historical knowledge in digital spaces. These games not only function as entertainment but also serve as visual and interactive reconstructions of medieval artistic traditions, offering players an informal education in medieval visual culture.

Kingdom Come: Deliverance II and the Realism of Romanesque and Gothic Architecture

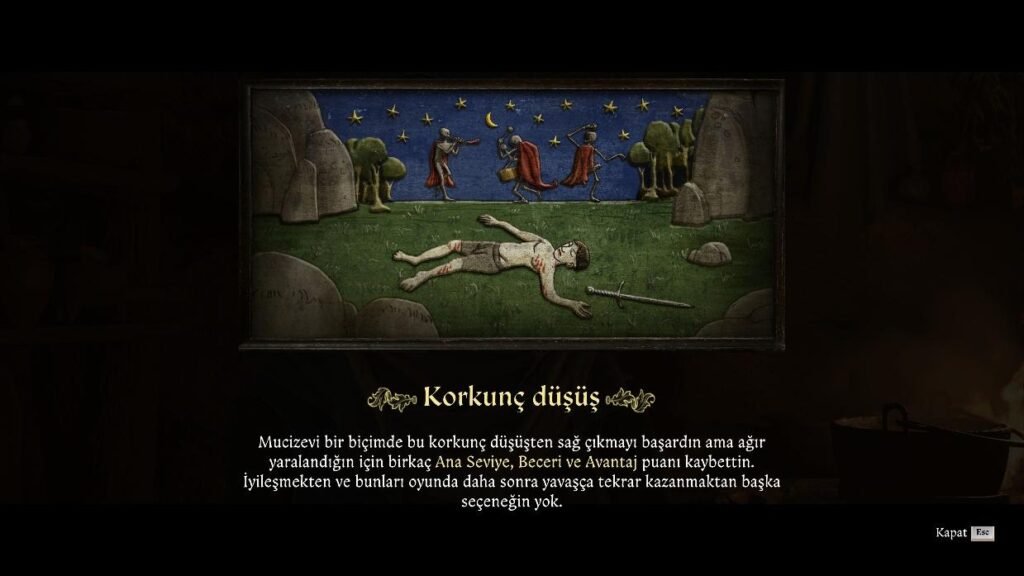

Kingdom Come: Deliverance II presents a highly detailed recreation of medieval Bohemia, incorporating architectural styles from the late Romanesque and early Gothic periods. The game’s depiction of churches, town halls, and fortifications demonstrates an adherence to the artistic principles of these periods, particularly in the use of ribbed vaults, pointed arches, and stained glass compositions. The game’s commitment to historical accuracy extends to its visual representation of religious iconography, including fresco cycles (fig 1.) reminiscent of those found in medieval Czech monasteries. The layout of urban centers, with market squares, defensive walls, and ecclesiastical structures, reflects contemporary medieval city planning, aligning with the 14th-century urbanistic models of Central Europe.

Source: Screenshot from Kingdom Come: Deliverance II (Warhorse Studios, 2024).

A particularly striking example of the game’s engagement with medieval religious art is the quest “Thou Art But Dust.” In this quest, players reconstruct an ossuary by gathering and organizing human remains into structured arrangements, a direct reference to the Sedlec Ossuary in Kutná Hora, one of the most iconic Gothic bone churches of the region. The act of assembling skull pyramids and bone piles echoes the artistic compositions of real ossuary sites, where bones were arranged in intricate, symbolic designs—often crosses, chandeliers, and arches—as a way to honor the dead and reflect on the transience of earthly life. The quest title itself is a direct nod to the memento mori tradition, rooted in late medieval Christian theology and visual culture, wherein reminders of death served as moral prompts for spiritual reflection. (Fig. 2)

Source: Screenshot from Kingdom Come: Deliverance II.

This mechanic also resonates strongly with the Danse Macabre tradition, a widespread 15th-century motif depicting skeletal figures leading people of all social classes to their graves, emphasizing the universal inevitability of death. By engaging players in the physical act of arranging the dead, the game not only recreates the functional aspects of ossuaries but also invites reflection on the theological and aesthetic meanings of death and decay. The player becomes an agent of ritualized burial, reenacting a visual and symbolic order that once permeated late medieval devotional practices. Through this design, Kingdom Come: Deliverance effectively bridges art history and interactivity, transforming a digital mechanic into an embodied memento mori experience.

Source: Screenshot from Kingdom Come: Deliverance II (Warhorse Studios, 2024).

Conclusion

As this study has suggested, modern medievalist video games are not merely escapist entertainment; they are also sophisticated visual systems that absorb, reinterpret, and project art historical knowledge into interactive environments. By examining Kingdom Come: Deliverance II it becomes evident that these games draw upon medieval and early modern artistic traditions to craft spaces of ideological, theological, and aesthetic meaning. The reconstruction of Romanesque and Gothic architecture here is mirrored by the symbolic juxtaposition of Norse and Christian iconographies, the grotesque allegories of witchcraft, or the visual theology embedded in sacred digital spaces in Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, and Diablo IV: each title contributes to a contemporary reimagination of the Middle Ages.

In doing so, these games not only render historical visual languages accessible to broad audiences, but also revive the persuasive power of images in a new medium. Their use of architecture, iconography, and spatial design to structure narrative and belief underscores the enduring relevance of visual culture in shaping collective memory. As such, video games emerge as powerful cultural texts—spaces where the past is not simply represented but actively negotiated, questioned, and visually reconfigured.

Bibliography

Brown, Michelle P. The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality and the Scribe. London: British Library, 2003.

Fernie, Eric. Anglo-Saxon Architecture. London: Pindar Press, 1983.

Freedberg, David. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Gertsman, Elina. The Dance of Death in the Middle Ages: Image, Text, Performance. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010.

Gibson, Walter S. Hieronymus Bosch. London: Thames & Hudson, 1973.

Koudounaris, Paul. The Empire of Death: A Cultural History of Ossuaries and Charnel Houses. London: Thames & Hudson, 2011.

Mâle, Émile. Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Nees, Lawrence. Early Medieval Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Zika, Charles. The Appearance of Witchcraft: Print and Visual Culture in Sixteenth-Century Europe. London: Routledge, 2007.

Ludography

CD Projekt RED. The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. PC/PS4/Xbox One. Warsaw: CD Projekt, 2015.

Ubisoft Montreal. Assassin’s Creed Valhalla. PC/PS5/Xbox Series X. Montreal: Ubisoft, 2020.

Warhorse Studios. Kingdom Come: Deliverance II. PC/PS5/Xbox Series X. Prague: Deep Silver, 2024.

Blizzard Entertainment. Diablo IV. PC/PS5/Xbox Series X. Irvine: Blizzard Entertainment, 2023.

Thank you, Baykar!

I’ve got a question about ethics. Human remains are a tricky subject in archaeology. There’s a whole discussion about how to handle them for education or research purposes – and even some who argue they should not always be left ‘out in the open’ for people to ogle or study.

There are some (like Meghan Dennis) who have done some work in thinking how virtual environments should handle these concerns.

Since you envisage KC:D II as a potential educational tool, do you think it does enough representing the complexities of dealing/exhibiting human remains? If not, what sort of work do you think a human educator would need to do instruct learners on archaeological ethics?

Thank you for this excellent and necessary question. I would say that Kingdom Come: Deliverance II does not directly engage with the ethical complexities surrounding human remains, at least not in the way archaeologists or heritage professionals would require. The quest “Thou Art But Dust” emphasizes themes like memento mori and vanitas—so it aestheticizes the idea of mortality through spatial design and ritual action, rather than critically interrogating the politics of display or respect.

That said, the ossuary setting—very likely inspired by the Sedlec Ossuary—does evoke a strong emotional response. Its use of sacred architecture, shadow, and silence can provoke a sense of reverence. But I agree: if this game were to be used as a teaching tool, a human educator would absolutely need to scaffold the experience with critical reflection on archaeological ethics. Questions like: who do these remains belong to? What does it mean to display the dead for visual impact? And how do different cultures view the care of the dead?

Scholars like Meghan Dennis, as you mentioned, have shown how digital spaces inherit real-world ethical dilemmas. Without context, the ossuary in the game may risk aestheticizing rather than responsibly engaging with death. So, while the game provides a meaningful space for exploring mortality, it does not substitute for real ethical discussion.

Thanks for the paper! Have you considered or do you have thoughts on the potential issues with implementing these kinds of sacral languages in games – in particular, I think of whether implementations reduces audience’s sense of sacral impact by attaching a non-faith gamified goal to engaging with these spaces?

And, secondly, I think your description of these images as being related to “persuasion” is really interesting. Do you think that there’s a potential issue in high-fidelity use of medieval visual reconstructions “selling” a wider story and set of character cultural attributes that might be much less close to medieval models? Do we risk fooling ourselves with aesthetic quality but losing the wider socio-cultural context sometimes?

This is a very important issue. As you rightly point out, the tension between aesthetic impact and spiritual or cultural depth is not new. During the period of iconoclasm, for example, it was argued that the visual mastery of sacred artworks could distract believers from genuine faith, sparking major theological and political crises. That historical debate resonates with your question: in highly realistic digital environments, do we risk being so aesthetically persuaded that we lose touch with the deeper socio-cultural context?

However, in historically grounded games like Kingdom Come: Deliverance, I would argue that the opposite potential exists. Rather than displacing cultural context, visual fidelity and artistic detail can inspire curiosity and encourage further inquiry. These representations may act as gateways—especially when supported by pedagogical framing or reflective gameplay design—helping audiences engage more deeply with the cultures and histories being depicted. In that sense, the “persuasive” power of such imagery could be pedagogically productive rather than misleading.

Well done, Baykar! How can developers better bridge the gap between the imagery of the fantasy Middle Ages and that of the historic Middle Ages? Is it by being more specific in their point of reference? Or perserving more accurate contexts?

Thank you! I believe the most effective way to bridge that gap is to begin with a rigorous, interdisciplinary engagement with the specific historical setting being represented. It’s not enough to draw from political or military history alone. Developers need to incorporate insights from sociology, cultural anthropology, theology, and crucially, art history, as these disciplines collectively shape the visual and ideological fabric of the Middle Ages.

Once that foundation is established, creative interpretation should follow—not to distort the past, but to transform historical knowledge into meaningful aesthetic and narrative forms. When developers strike this balance—between historical depth and imaginative expression—they can create fantasy worlds that are both compelling and culturally resonant.

Thanks for your brilliant paper! I especially enjoyed your conclusion pointing on the effects of visualisation in forming collective memory. As computer games act as a particular negotiable field of agency – what do you think: what kind of images had the producers in mind, what type of (visual) Bohemian history do they want to present us in KC:D II?

Thank you very much—that’s a great question. Naturally, without direct access to developer interviews or production notes, it’s difficult to say definitively what images they had in mind. But based on the game itself, I would argue that Kingdom Come: Deliverance II presents a visual narrative that closely aligns with historical records.

The architectural features, clothing, religious structures, and scenes of daily life all reflect what we know of 14th-century Bohemia with remarkable fidelity. This level of visual accuracy shifts the tone of the game at times—it feels less like a conventional action RPG and more like a medieval simulation/RPG. This suggests a conscious design choice by the developers to evoke and reconstruct a tangible sense of historical context through immersive realism.

Thanks Baykar, an interesting read… 🙂 I wonder, are there any aspects of art history or iconography that you feel KC:D2 gets badly wrong? If so, does that matter? How does it affect the game’s educational value?

Thank you for your question. During my time with the game, I don’t recall encountering any major inaccuracies in terms of art history that felt particularly jarring. However, one thing that stood out was how limited the game was in its representation of religious iconography.

Many of the larger churches are inaccessible, which means we miss out on seeing how their interiors are designed—especially how fresco cycles might have been employed, which is a compelling question from an art historical perspective.

That said, in the few interiors we can explore, there are some well-executed cyclical fresco scenes based on biblical narratives, which were a nice touch. Likewise, small icons and decorative illustrations on chests were beautiful details, though they appeared infrequently. So while the game may not fully realize its iconographic potential, it still conveys a convincing historical atmosphere through selective visual cues.

Thanks for this thoughtful contribution, Baykar! I absolutely agree, today’s games don’t just expose players to medieval visual culture. They give that culture new life. Through spatial design, iconography, and architectural cues, games like Valhalla and Kingdom Come reassert the narrative power of the visual in ways that remain deeply resonant.

Thank you so much! I really appreciate your kind words—and I completely agree with your point. It’s exciting to see how contemporary games give new narrative force to medieval visual culture.

Great paper, Baykar! I research the connection between game mechanics and storytelling, so this is very interesting to me. The Thou Art But Dust quest indeed sounds like a good example of an embodied and spiritual gaming experience. But has it actually been successful in that regard? As far as you know, how much have players appreciated it?

Thank you so much! That’s a great question. Since the game is still relatively new, I haven’t come across any academic analyses of this quest just yet. However, from what I’ve seen in player communities, the quest has received a notable amount of attention.

On platforms like Reddit and Steam, there are numerous screenshots and discussions specifically highlighting Thou Art But Dust. Many players seem to find it aesthetically powerful and emotionally resonant, often praising its atmospheric design and thematic depth. So while we may not yet have academic feedback, the player response suggests it has already made a meaningful impact.

Perfect paper, Baykar!

From an architectural standpoint, the Kingdom Come: Deliverance series has always struck me as more than brilliant. I was wondering whether KCD II also contains any examples of “simulacra,” as was the case in Assassin’s Creed II, where, in late 15th-century Florence, there are monuments well known to the general public and expected to be seen, but which are in fact from a later period.

Thanks again for this great paper!

Thank you for your question! While I can’t recall a specific example of a simulacrum off the top of my head, I do believe it’s entirely possible that such instances exist in KCD II—especially considering the vastness of the world and the expectations players may bring to it.

That said, what struck me instead were some clever “reverse” cases: for instance, rather than presenting monumental buildings as already completed—even when they would still have been under construction during the historical timeframe—the game occasionally depicts them in-progress, with scaffolding and NPC stonemasons actively working on site. This kind of architectural realism actually deepens immersion and reflects a nuanced awareness of historical timelines.