By Stephen Yeager (Concordia University)

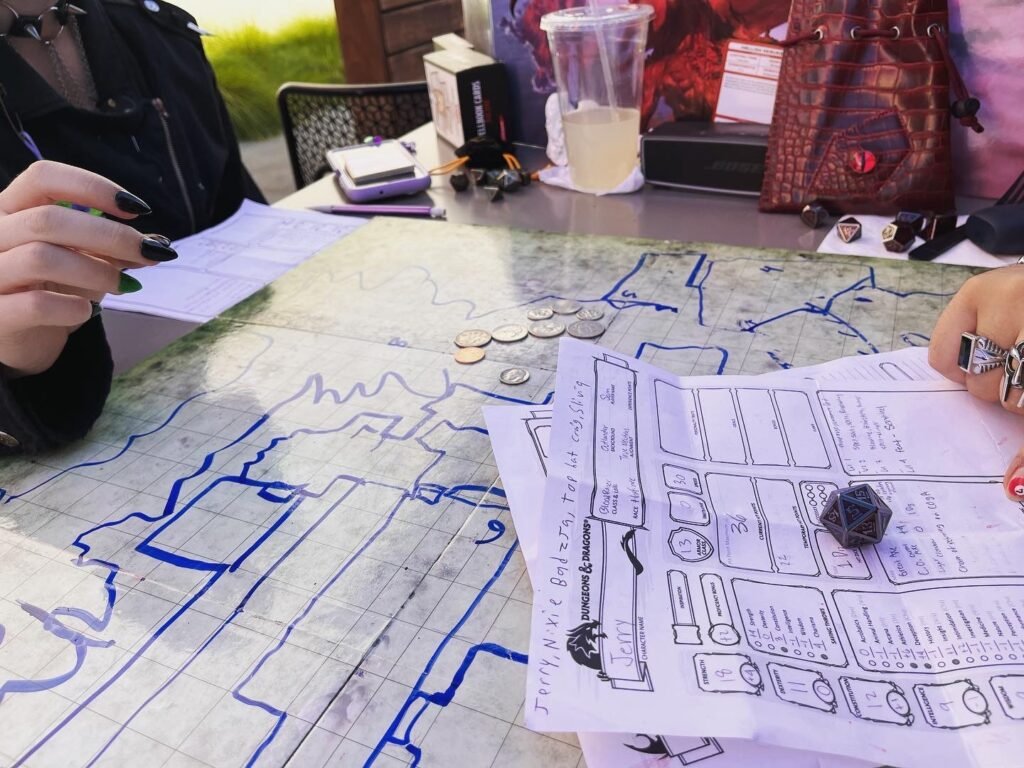

Social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and X should be categorized generically as free-to-play ad-based mobile RPGs, descended from the frameworks for collaborative storytelling developed for the medieval fantasy RPG Dungeons & Dragons (D&D).

In his book The Elusive Shift, historian of D&D Jon Peterson argues that a central mechanic of the game is its “experience points” or XP (2022, 96-102). When D&D players choose actions to shape the game story surrounding their characters, they roll dice, which determine if their actions succeed or fail. XP rewards player successes by improving the odds that future rolls will also be successful, thereby giving players more control over the shared emergent narrative of their D&D adventure.

Peterson documents a debate over whether D&D players should know the rules whereby XP is awarded or whether the game master alone should have this knowledge. Players who know the rules may engage in in “min/maxing,” setting aside story, character, and world consistency to maximize XP gain for its own sake. Of course it was impossible to prevent players from learning the rules, and now it is assumed by game designers that RPG players will be motivated by progression mechanics like XP. Accordingly, D&D began awarding XP in order to motivate players to immerse themselves in their characters.

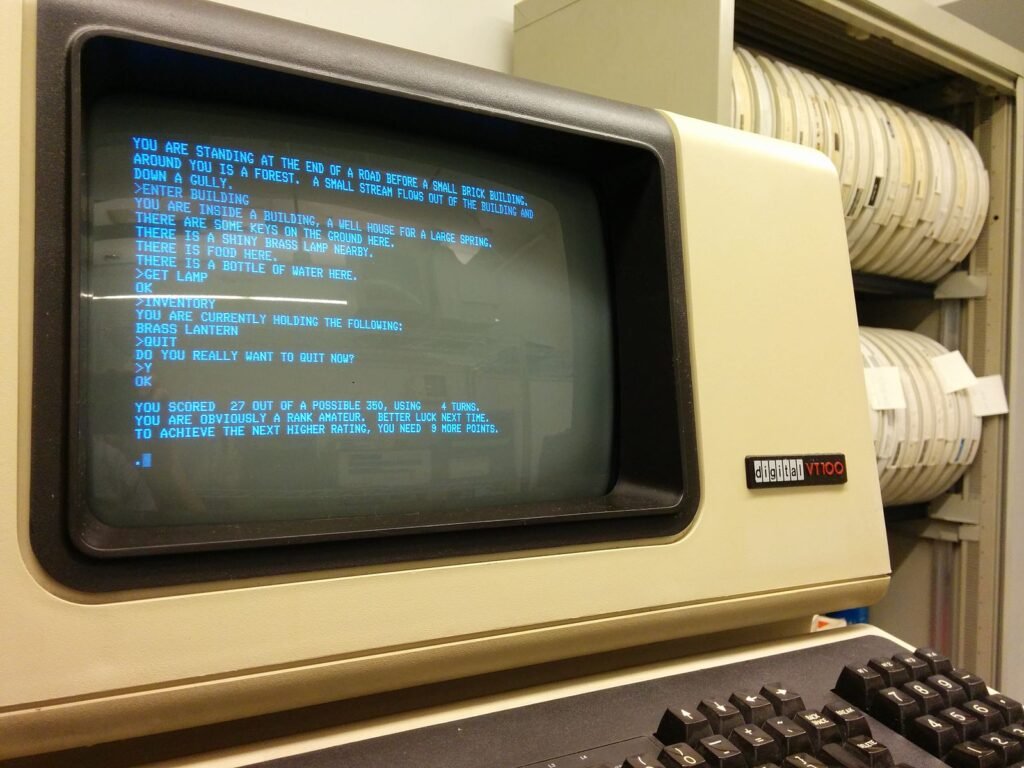

D&D emerged from an analog social network that began in the late 1960s around the magazine Avalon Hill General, which published want ads for wargamers who wanted to conduct games through correspondence (Peterson 2012, 5-6). In this same period, the US Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) developed ARPANet, the ancestor of the modern decentralized Internet. The first edition of D&D was published in 1974, and in 1976 the ARPANet programmer Will Crowther posted online the first major free-to-play D&D-based adventure game. The overlapping communities of wargame hobbyists, computer engineers, and RPG enthusiasts have relied on digital networks to stay in touch ever since, beginning with the platforms of the BBS (bulletin board system) and the MUD (multi-user dungeon). These in turn provided proof of concept for later social media.

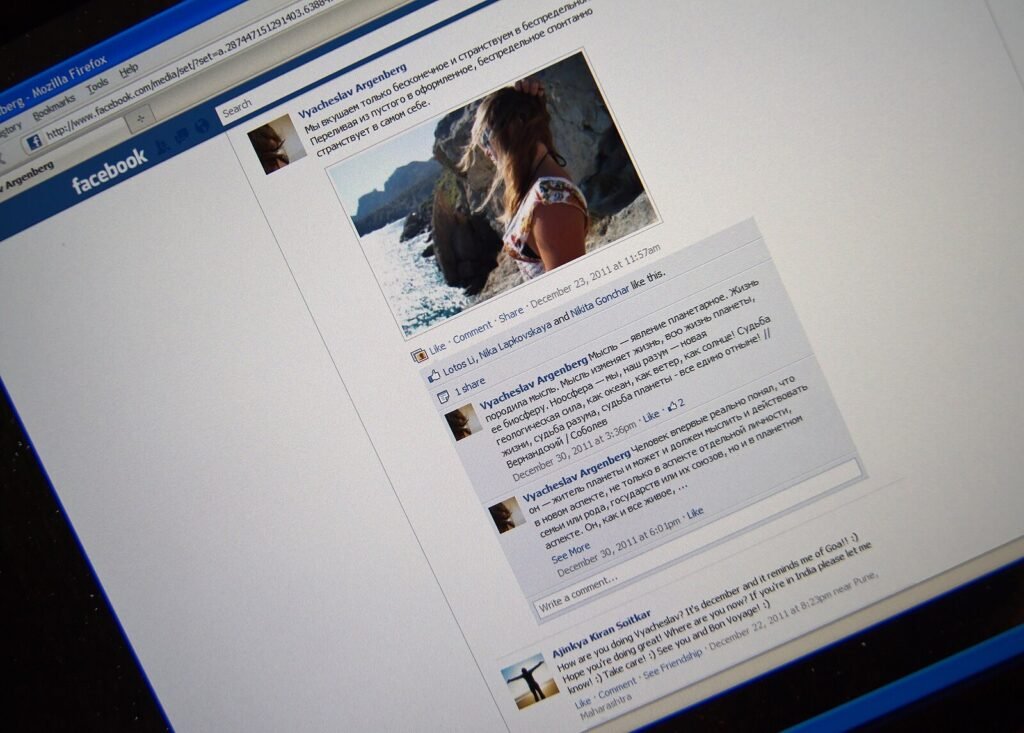

In 2006 Facebook introduced the first social media algorithm, EdgeRank. EdgeRank curated the posts on each users’ feed, assessing what could be called the “XP” of each poster to promote certain posts over other posts. To “min/max” this algorithm, each user had to build the broadest network of friends possible and post as frequently as possible to make future posts even more likely to gain views, leading in turn to larger networks and higher-engagement posts. Like XP, this mechanic rewarded “staying in character,” which is to say the development and promotion of a “brand.”

Like D&D, social media algorithms draw users into a shared fantasy world of collaborative storytelling by rewarding consistent storytelling with greater personal control over the shared emergent narrative. This parallel in game mechanics probably arose because of the central role played by fantasy RPGs in the development of digital networks over the last 50 years.

Realized I didn’t include a works cited:

Lessard, J. (2013). Adventure before adventure games: A new look at Crowther and Woods’s seminal program. Games and Culture, 8(3), 119-135.

Peterson, J. (2012). Playing at the world: A history of simulating wars, people and fantastic adventures, from chess to role-playing games. San Diego, CA: Unreason Press.

Peterson, J. (2020). The elusive shift: How role-playing games forged their identity. Boston: MIT Press.

Thank you for these interesting ideas, Stephen. As you point out, social media engagement can be easily compared to the role-playing dynamics embedded in RPGs like Dungeons and Dragons. I would like to ask if you could expand on this, especially when we think about trolls or social-media profiles that disseminate problematic understandings of the past.

The original etymology of the word “troll” for what we might call an Internet provocateur does not come from the mythological monster, but from the style of fishing, where your boat goes by at a slow pace and you let the line dangle in your wake. It’s related in this sense to the idea of “engagement bait.” The poster is a fisher or trapper, the person who engages with the content is the prey to be captured, killed, and exploited. This concept of what a social media user is motivated to do emerges from the mechanics I’m talking about: for the minimum contribution of resources, you want to maximize the impact of your future activities, so that you can then leverage that impact to increase your impact further.

This is parallel to how XP motivates D&D players. There, too, you want to take out the biggest, most powerful monsters with the minimum resources available. The big monsters are worth the most XP, and if you take them out in a clever way that fits with your character’s strengths and limitations your DM will probably give you a bonus. In both cases, the most efficient strategy is to play a character. As we know from Poe’s Law, the more you try to sound like a particular sort of character online, the more people will believe you are that character, and the more engagement you’ll get from other characters (who will promote their own brands if they either say outrageous arguments against you, or if they agree with you in ways that are even more outrageous than whatever you originally said).

My main point, then, is that this is not just an analogy between D&D and social media, but probably a direct influence of D&D on social media: hence, for example, the predominance of the other meaning of the word “troll,” which imagines one’s fellow posters as D&D monsters one has to “fight.”

Thanks, Yeager, this is an interesting perspective of social media. It makes me think about the metagame aspect of social media. Unlike table-top RPGs, I don’t think today’s social media are conducive to rule negotiation and other metagame-related activities. What do you think about this?

No, not at all! Though my sense is that many social media companies try to perform “rule negotiation” to maintain credibility among their userbase, if there is no sense of fairness you lose your userbase. X in particular would be very germane to a retrospective study along these lines. I wouldn’t do it myself but I’d love to read it!

Thanks. Now that you mention it, I kind of see the similarities between X and a game or game series that loses a significant part of its player base because of a barrage of inane patches, haha.

Exactly!! 😂😂

Thank you so much for your interesting paper, Stephen! I was wondering if you could relate this proximity between D&D and social networks with the process of gamification, which is being increasingly implemented in numerous areas to increase productivity and turn “boring” tasks/processes into appealing ones. Thanks!

“Gamification” is very much in the background of what I’m describing here. My own thinking at the moment depends heavily on Patrick Jagoda’s book Experimental Games (2020), where he connects it back to economic game theory in the mid-century. Jumping off from his work, I’m interested in quite broad definitions of “gamification” that would treat the concept as a motivation strategy with quite long-standing antecedents. Perhaps any time where you have an explicit or implicit hierarchical ranking system which rewards one’s own performance of (self-)control with movements up the ranking / even more control, then that system is “gamification.” If that were the case then an example would be the early Christian asceticism of the Desert Fathers, who according to their Sayings were engaged in a more of less constant game of one-upsmanship on who can go the longest on water and salt, or without ever talking to anyone. The key element of D&D and social media that fits it into this broader sphere of “gamification,” then, would be the way that the shaping of your character requires control, and the way the development of that character is rewarded through hierarchical progress, which in turn grants the user / player / monk or whoever with more and more control over a shared story.

I can see a similarity between this process of convergence and C. Thi Nguyen’s theorization of gamified spaces and value capture. In fact, Nguyen himself makes the analogy with social media.

Given this origin story you described, how to you see the shift from more *social* kinds of social media and those less predicated on the social graph? Like Twitter post-retweed function, which allowed people to broadcast outside their social circle, or TikTok, in which the algorithm has a much more deterministic role? Is social media still beholden to its D&D roots or is it morphing into something else?

This is a difficult question to answer, because it depends on how you define D&D! A lot of different games have gone under that name at different times, and in the first edition especially it seems like no two players played it the same way. If we limit “D&D” to the specific series of game systems and settings that have been the intellectual property of first TSR and then The Wizards of the Coast, then we would have to say yes, social media and D&D are quite distinct from each other, though even then there are plenty of signs of co-evolution. Critical Role is both an important quasi-official D&D product and an influential podcast that proved there were audiences for a certain kind of storytelling; Roll20 is both an important new way of playing D&D remotely and a specialized social media platform; etc. And if we take the broader sense of what D&D “is,” to see it rather as a shared genetic lineage for RPGs in general, then the difference between Facebook and the D&D 5th edition is more like branches growing from the same tree. I haven’t followed up on it yet, but I have an intuition that there’s something to be made of the fact that the UNIX operating system is just a year older than D&D. Perhaps a good analogy to what I see happening with D&D progression mechanics in social media can be found the way that there are parts or concepts of UNIX that belong to software languages that are not UNIX–which, broadly conceived, would have to include those aspects of languages that are specifically designed to do something Different from UNIX out of annoyance at its limitations, so that they are in a Hegelian sense Negations of UNIX. Then again, this very loosey-goosiness is itself a way that social media resembles D&D: in both cases the systems are in flux, but there are themes.

Since you mentioned Critical Role, what do you make of the scholarship that attempts to study Actual Play as its own thing (Emily Friedman comes to mind)? Is there anything in it you think might be useful to understand modern social media – and in what social media might envolve from here?

Realizing I wandered away from the main question with my other post! Ultimately I would say that all of the examples you’re describing are different variations on the same theme. Retweeting gets outside the social circle just to expand it. TikTok is not so different from randomized encounters, which are a big part of some D&D campaigns and not others. For all the variety we’re talking about, I’m not sure we’re getting outside of the basic incentive structure, with its basic imperative to tell a consistent story in exchange for more control over everyone else’s story.

So basically, successful influencers are highly developed power gamers? Love that concept, of meta-gaming the game itself. Some intriguing ideas here, Stephen.

Yup, that’s basically it! 😂 Thank you Robert, and thank you to everyone for your questions!

This is a really interesting concept! I’ve always thought of social media as a sort of game but I never thought of making the connection to D&D. But with that being the case, does that mean that ultimately in social media we are at the whims of a DM who doesn’t know or care about its players beyond keeping them there (the algorithm)? Or could mods be seen as DMs?